|

Al Jowf Speleological Survey

UNDERGROUND IN AL GREYA

Photos © 2007 by J. Pint or M. Al-Shanti; updated September, 2013

|

I am in Jeddah, once again working for the Saudi Geological Survey and eager to be back in a desert cave after a two-and-a-half-year absence. My first field trip will be to a limestone area in the far north of Saudi Arabia. “I missed you on my last trip to Al Greya,” says Mahmoud, with whom Susy and I explored many a cave. “I can’t find anyone else here willing to go with me into tight passages that no sane person would crawl into.”

Well, I took that as a compliment and now here we are, heading north from steamy Jeddah in two Landcruisers piled high with camping and caving gear. “We’ve found a new route to the far north,” says Mahmoud, “which you will love. We are going to drive straight across the Nafud Desert.”

Anyone who has seen Lawrence of Arabia ten times will remember that the Nafud is the scorching hot, pitiless desert where the Lawrence and his Bedouin friends nearly died trying to sneak up on the Turks in Aqaba from a totally unexpected direction. Remembering Aqaba, I pull out my map of Arabia and notice that Al Greya, where the caves are, is as far north as Petra, in Jordan, where I remember shivering in an unheated hotel room. Maybe I should have brought much warmer clothes, but now it’s too late.

Four hours north of Jeddah, we are hit by our first sandstorm. The world turns yellow. Only the AC saves us from choking on the fine dust swirling around our car. Visibility is reduced with each kilometer we drive until we are forced to a crawl. Can’t see more than two meters ahead and suddenly it begins to rain. Water plus fine sand and dirt equals mud. One side of the car is dripping with it when we finally emerge from the sandstorm.

Left:

mud from on high Left:

mud from on high

Right: Camping in the Great Nafud Desert |

INTO THE GREAT NAFUD

After driving in a straight line through the town of Hail, we take a brand-new paved road heading straight into the Nafud. Unfortunately, it is now pitch dark and all I can see is inky blackness on both sides of the highway. Finally, we stop to camp, but with only soft sand surrounding us, we are forced to spend the night next to a microwave tower. Instead of enjoying the sounds of the desert which we can’t see, what we get is the roar of a generator under the tower. Thus, I am forced to use earplugs in the Nafud Desert!

Next day, we can see where we are—in the middle of a great sea of sand. I should only have an eye for the beautiful dunes, but the truth is I am fascinated by the highway we are on. Only one side of it is finished, so we can see the techniques being used to build the other half of it. In some places we can see up to twenty bulldozers literally resculpting the dunescape, filling huge valleys with sand and leveling some high places. Mahmoud points out that most of the construction is being done with materials found locally. No, I don’t mean sand. These guys are actually digging down beneath the sand and extracting the dirt and gravel they need for their work. “And when they want water,” says Mahmoud, “they just sink a well.”

Of course they are building a road similar to the one crossing the Rub’ Al Khali. They create a sort of “artificial dune” with just the right amount of curvature and then they put a road on top of it. On this curved surface, the sand just blows off instead of accumulating, so you don’t get the “buried highways” which plagued the first road builders in this country.

|

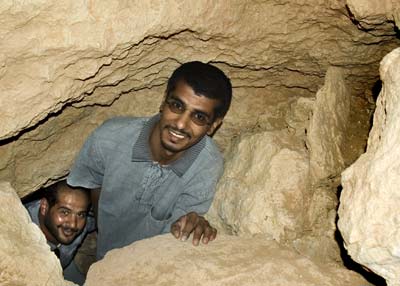

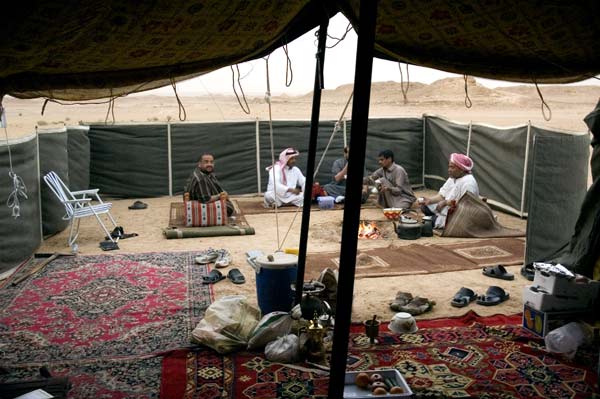

Monday, April 9, 2007. We arrive in

Sakaka at 10:30 AM and meet Awad Al Falleh, Majed Al Auda and Hytham Al Auda.

Each of their trucks has the logo “FriendsofDesert.Com” on the sides, on

color posters of Mahmoud admiring stalactites in a cave. We joke about

“royalties” as the team from Sakaka shows us how they have adapted their

vehicles for the desert. On one side they have two spigots: one gives you

soap and the other water (from a built-in, 60-liter tank). They are not

really an organization, explains Mahmoud, but three friends who spend a

great deal of their time in the desert and are fully committed to preserving

its beauty. They hope to learn as much as possible about cave exploration

and conservation during this trip.

|

|

We load up with food and are soon off road, roaring through hills covered with sand and dotted with black rocks. Half an hour later we come to the first limestone outcrops. We are no longer in the volcanic Arabian Shield but have entered the western end of limestone beds which stretch all the way to Ma’aqala, where Saudi Arabian speleology was born in the 1980s. An hour later we come upon a pickup in a very lonely spot. A man next to it waves his arms wildly and comes running. “You must not leave here without helping me!” he shouts, trembling and crying. He tells us his car broke down yesterday and his brother set out walking for help at eight this morning. We give him our Thuraya phone to call his relatives and he learns that his brother is okay and help is on the way.

Caravaning like this, you must constantly keep an eye on the car ahead of you. We only slip up once and suddenly have no clue where to go. We follow our noses and end up finding the best-looking prickly rock (karst) I’ve ever seen in Arabia. It’s dolomitic limestone, very hard. I take the waypoint and soon we reconnect with the others...

| ...A

little later, we stop for a rest and find we’re surrounded by pieces of

bizarrely shaped, highly polished, curiously colored chert. As an

incurable chert collector, I’m impressed and can’t resist taking some along...

|

|

A little later we come to green meadows guarded by ferocious sheep dogs. Mahmoud says some kind of gypsies (salub, or people of the cross) live here.

Now we are in Bowaitat, which means “The Houses.” All around us are the remains of homes built of flat slabs of limestone. Some are round with domed roofs, built igloo style. Awad tells us this area was lived in 5,000 years ago, but the houses were rebuilt periodically. They apparently didn’t use any sort of mortar or packing to keep out the wind. A picturesque tower we saw here five years ago now sports bright red graffiti. A lot more friends of the desert are needed in order to protect treasures like these. This settlement also has what looks like an ancient qanat (underground aqueduct) or maybe just a string of connected wells, for their water supply. “Maybe they learned this technique from the Nabateans,” suggests Mahmoud, “or maybe the Nabateans learned it from them.”

The Tower of Bowaitat, before and after... |

|

|

|

Suddenly Mahmoud says, “Listen to that airplane!” but the plane turns out to be a flat tire, cut by the sharp limestone.

Just at sunset, we arrive at Abid Cave and set up camp. For the next three nights, this is our home.

SQUEEZING THROUGH THE BOWELS OF ABID

|

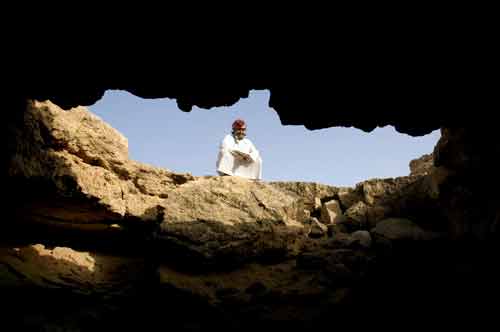

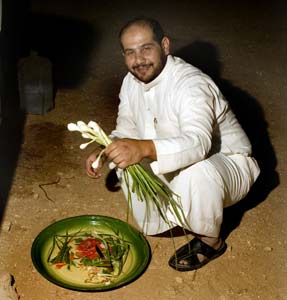

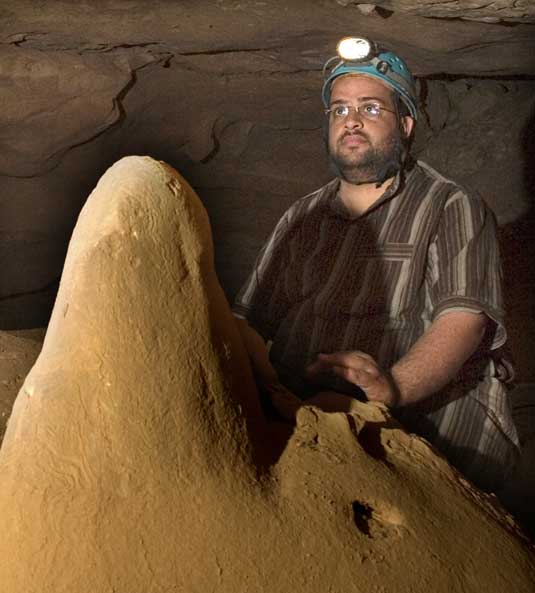

Next day, Mahmoud and I enter Abid

Cave with the three Friends of the Desert. We rig a handline to assist in

climbing down the entrance hole which is just a few meters deep. Inside, we

find a series of rooms gradually taking us deeper and deeper. To my

surprise, we come upon the only cave pearls we’ve ever seen in Arabia, apart

from those celebrated and still-growing pearls in

UPM Cave. The Abid

pearls look very old and seem to be the only calcite formations in this

cave...

|

|

| ...Eventually

we come to a hole about a meter in diameter that puts you into a

stoop-walking/crawling passage which immediately makes a U-turn. The walls

are now smooth and polished and a strong, cold wind is blowing in our faces.

It’s obvious that this passage has received huge quantities of water

traveling at high speed. Debris stuck to the ceiling shows that the tube

fills completely with water and we speculate how long ago there was so much

water in this place. “This debris could be from thousands of years ago,” we

say and then discover, to our chagrin, half of a very modern-looking shoe

stuck near the top of the tunnel. Later we find two-liter plastic Pepsi

bottles (one is still half full and looks drinkable) and figure they must

get some pretty powerful storms in these parts. “I sure hope it isn’t

raining out there right now,” I tell Mahmoud, remembering the dark clouds we

had seen on the horizon this morning.

|

|

| ...At

the end of this passage we come to a T where we find water dripping from the

ceiling. Hmm, maybe it is raining up there! The two passages we have

come to at this point eventually become too tight for crawling, but wind

whistles through them. We decide to head back and that is when Awad whips

out a big trash bag, which we help him fill with bottles and cans as we make

our way out. I think we cavers could learn a lesson or two from these Sakaka

guys. Before leaving the cave, Mahmoud hides candles in one of the rooms

(where there is less wind) and we do about twenty takes to get one good

picture.

|

|

After lunch we find two smaller caves not far away. They look ready to collapse but you can hear wind roaring inside and they may be connected to Abid. We find seashell and worm fossils in the crumbly rock around the entrances.

THE VANISHED CAVE

After we go to bed, a strong wind arises and tests our patience. This especially goes for Mahmoud, who gets “slapped in the face” all night long.

Left: Mahmoud

in his tent, early the next morning. In all fairness to Eureka, we must

mention that he hadn’t put in any stakes... Left: Mahmoud

in his tent, early the next morning. In all fairness to Eureka, we must

mention that he hadn’t put in any stakes...

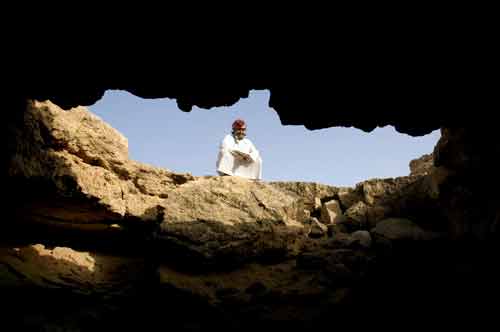

Right: Hytham "murdering the onions." |

After breakfast, we drive to Dharwiah Cave which is only four kms from Abid. Here we drop stones down the two entrances and conclude that this hole is much deeper than previously estimated. As we had left the vertical ascending gear at the campsite, we are discussing how to rig the cave when we spot calcite in the rock not far from the lip of the big hole. Then something that looks like a stalagmite is noticed near the small hole, buried in a dirt ridge above the hole. Mahmoud’s geological instincts are aroused and he begins to dig out the formation, which is about 70 cm high and a meter and a half around. He finally decides it’s a fallen stalagmite. We are amazed. It appears that the surface we are standing on was once the floor of a cave which has eroded away over the eons.

| ...Mahmoud

is captivated by this lone survivor of a bygone cave and begins to dig it

out from the bank of earth and gravel covering it. While he digs, I go off

with Majed and Hytham to look at other holes Majed knows in this area.

|

|

We examine a collapse which is probably a cave entrance, but is now completely filled with dirt and debris. Next, we see a set of three holes all in a straight line. These seem to be man-made and opening onto a tunnel about 2.5 meters below the surface. We many be looking at part of a qanat, or underground aquifer built with techniques from Persia, similar to Qanat La Venta which we foolishly believed was a natural cave until we were enlightened by archeologists. In this area we have seen other strings of man-made holes, near Bowaitat (30 kms NW) and Kfetan (29kms NE). Maybe these are just elaborate water collecting systems. It would be interesting to know their age.

STALAGMITES BY THE DOZEN

| ...Next,

we go to a big collapse which looks just as plugged up as the previous one.

Nevertheless, I go through the motions, moving along the wall of rubble,

looking for a hole—and finding one! It’s only about 75 cms in diameter and

has no airflow, but I see darkness beyond and I crawl into it. One glance

inside and I shout to my companions: “Stalagmites! Big ones!” They have no

helmets, but can’t resist joining me to have a quick look around.

|

|

| ...The

cave has huge blocks of breakdown lying on what is essentially a flowstone

floor. There are stalagmites all over the place and stalactites, many of

which are either broken off or crumbling from weathering. At first I

attribute the breakage to vandalism, but later Mahmoud points out that this

cave has been subject to various forces, from collapses to flooding.

Everything we see is covered with a layer of brown dust.

|

|

We go back to tell Mahmoud and the others about our find and soon we are surveying what we now call Dahl Majed. A closer look at the ceiling reveals an area filled with cauliflower and helictites...

| ...At

one end of the cave, we find a great wall of flowstone stretching from

ceiling to floor, with an opening at the bottom. We crawl in and find a

second room. It has upper passages with strong airflow, but the ceiling here

looks very fragile and ready to collapse. The cave goes, but we are not

willing to risk our necks to see where or how far it goes. Maybe a

geophysics survey from the surface would show this connects to Dharwiah,

only 2.6 kms away.

|

|

While we are inside the cave, Abdulwahed has collected arrowheads and a cutting tool made of chipped chert, reminding us again that this area was inhabited long ago.

| We head back to camp, just as a strong wind begins to rise, blowing sand and dust everywhere. Awad and company, however, are ready for any contingency and unroll a collapsible “instant wall” which indeed gives us welcome protection from the cold wind.

|

|

Just after sunset, we see three goats walking by in the distance. “They are lost,” says Hytham and he jumps into his truck. “I will catch them and we’ll keep them here until the owner comes along,” he says and off he roars into the darkness. Well, we don’t see hide nor hair of him for an hour, just an occasional flash of light in the far distance. “Don’t worry, he has GPS,” say my companions. Finally, even they get a bit worried and drive two cars to the top of nearby hills and flash emergency lights. At last, Hytham appears. Amazingly, he tells us that he caught the goats and somehow found their owner ! After giving the animals to him, he then found his way back to our camp. As we are surrounded by hundreds of very similar low hills and it’s pitch dark, I assum it was the GPS that led him back to us. “GPS? No, the battery is dead,” he says without blinkineg an eye. What remarkable people!

Next morning, as we break camp, Abdulwahed finds a seven-centimeter-long centipede hiding under his pillow. “That’s nothing,” says Mahmoud, “on a previous trip, Sa’ad, lifted his pillow to discover not one but two scorpions under it, fighting each other to the death.”

Left:

Abdulwahed's centipede Left:

Abdulwahed's centipede

Right: Mahmoud photographing our campsite in Al Greya. |

A lone white egret watches us from a nearby hill as we collect all our trash and burn it. Friends of the Desert have come to the same conclusion as we about this. Carrying garbage to the nearest gas station, American-style, doesn’t work out here, as it just ends up right back in the desert anyhow.

Our Sakaka friends are disappointed that we don’t have time to accept their invitation to a meal on the way back, so they radio ahead and we find Hytham’s brother waiting for us in Sakaka with gifts of extra-virgin olive oil, honey and deliciously sweet dates, all products of Al Jowf, which is the name of this region in the northwest corner of Saudi Arabia.

|

We

drive into the Nafud and camp out again, this time far from any towers. At

6:00 AM we are awoken by the RAKATAKATAKA BEEP-BEEP-BEEP of bulldozers and

trucks just a few hundred meters from us. It’s the new song of the Nafud,

welcoming us back to civilization!

|

|

John Pint

|

|

|

|