Of course, when you breathe this stuff in, it stays in your lungs for the rest of your life, like asbestos !

HELICOPTER RESCUE

AT UM QARADI CAVE

© 2005 by John and Susy Pint, Updated September, 2013

A serious accident is frightening enough in itself, but if it takes place in the middle of nowhere, it suddenly becomes a thousand times more serious. This lesson hit us hard last week when we nearly lost one of our colleagues, Saeed Amoudi, in the barren wastes of Harrat Khaybar lava field.

It all began when Jamal Shawali, the black-bearded head of the Medina Earthquake Monitoring Station, sent us a CD full of cave pictures he had taken somewhere in Harrat Khaybar. Since we are already working on a report on Khaybar as the most promising cave area in Saudi Arabia, we jumped at the chance to see Jamal’s caves and on February 24, 2003, drove off to Medina.

“We prefer to camp under the stars,” we said and off we drove to the cave, which Jamal said was only seventy-two kms away. Well, 150 kms later, we found ourselves winding our way through desolate lava beds in total darkness, wondering how Jamal was going to find this cave without driving right into it.

“Didn’t you say it was 72 kms away, Jamal?”

“Yes, of course… by GPS,” he replied with a twinkle in his eye, proof of how quickly we are all acquiring “satellite vision.”

The walk-in entrance to the cave.

|

|

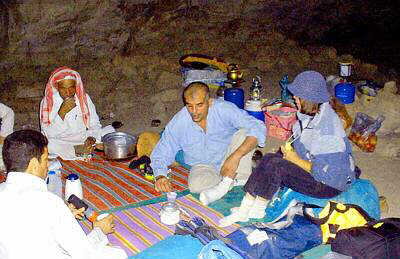

A brisk wind was blowing and it was getting cold. Jamal showed us two more entrances to the cave, one of which was horizontal. Soon we were carrying our boxes, bundles and bags down into a flat spot some twenty meters inside the cave, which, of course, was pleasantly warm.

Tea time inside the cave...

|

|

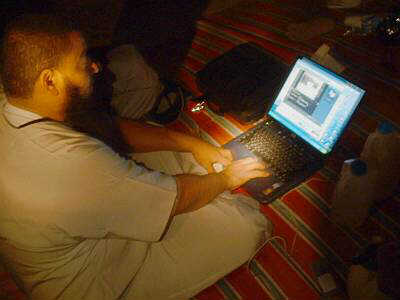

...And then, it's show time as Jamal reveals more cave pictures on his hardy, cave-proof laptop.

|

|

A quick walk showed us the cave was only a hundred or so meters long and about 14 meters wide at most points. It was a lava tube, but instead of exhibiting the usual smooth surface, the walls and ceiling looked chunky and deteriorated. No lava stalactites were to be seen anywhere and it could be that the entire inner layer of the original tube had long ago spalled off.

The typical wide arch of a lava tube.

|

|

Detail of the ceiling and side wall: thin on top and not exactly smooth.

|

|

The distance from ceiling to floor was only about four meters, suggesting that we were standing on many meters of accumulated sediment. Digging deep might reveal lava levees and fallen bits of the original ceiling, not to mention archeological finds and a few million years of pollen deposits.

Floor of the cave seen from above. Note the healthy plant life.

|

|

That night, few of us slept peacefully. I had nothing but nightmares and in her dreams, Susy saw pale, sober-faced individuals telling us over and over to get out of the place.

By the light of the next morning, we could see that the area just outside the cave’s horizontal entrance had once been covered with buildings. The outlines of ancient walls are clearly marked by blocks of basalt.

When I reached Saeed and saw his face covered with blood and his leg twisted unnaturally, and blood spattered everywhere around him, my heart nearly stopped, because I had imagined he had simply slipped and fallen while walking. But apparently he had tumbled from a standing position on the roof rack, perhaps pushed by a sudden gust of wind. It was a long distance to fall, and all the worst to land on rough, volcanic rocks.

This situation looked deadly serious. Saeed was alive, thank God, but barely conscious and obviously in deep shock. By then everyone was around him and, hands trembling, we began to apply the various procedures we had been taught during our First Aid and Cave Rescue course in Lebanon. It was much harder to do those things under the stress of a real accident, of course, but I was especially struck how very difficult it was to THINK clearly. Obviously it is better to have things like splints, cloth triangles, etc. ready for use, avoiding the need for improvisation, which doesn’t come easy under stress.

At this point, we realized how foolish we were not to have bought a speleo rescue stretcher or at least built a simple one of plywood. We had no safe way to move him, for example, to the inside of a Land Cruiser. However, the serious possibility of internal injuries and broken bones told us to forget about transporting Saeed over those rocky tracks. “Jamal has friends at the Civil Defense in Medina,” said Mahmoud. “We’re going to call for a helicopter.”

The helicopter lands...

|

|

The Civil Defense Unit in action...

|

|

A race against time.

|

|

The rest of us packed up and returned to the SGS earthquake camp. After a few hours, we were relieved to learn that Saeed had no broken bones (Mahmoud insisted on x-rays of every inch of his body) and his head and leg wounds were being stitched up. Later, in Jeddah, CAT scans would verify he had no internal injuries. That afternoon, Saeed was released from the hospital. He had stitches on his face in two locations and still couldn’t walk on his leg despite pain-killers. Apparently the wound had gone all the way to the bone. But he was alive and even joking about not missing the next cave trip.

We spent the night at the SGS Medina camp, despite the certainty of inhaling rock-wool dust and enjoyed countless cups of tea thanks to Jamal’s attentive assistant, Naheel. On one occasion, Susy helped out by pouring the tea for me. I told her, in Spanish, to give me only “un poquito” as I felt I was already swimming in tea. But Naheel noticed the half-empty cup and then carefully explained to Susy how to do it right and I got my full portion after all.

John Pint