|

|

Umm Jirsan Lava Tube

|

The full story of Saudi Arabia's longest cave, now under study by archaeologists (Photos by John Pint unless otherwise indicated) Adapted from chapter 17 of

the book Underground

in Arabia by John Pint

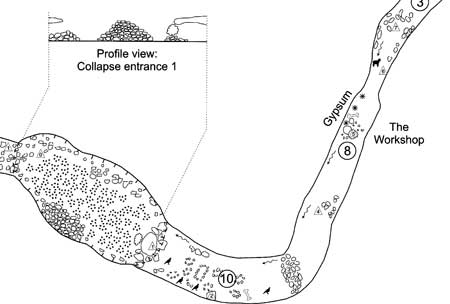

By John Pint Recently, Dr. Mathew Stewart and members of the Palaeodeserts Project published "First evidence for human occupation of a lava tube in Arabia: The archaeology of Umm Jirsan Cave." Here we find scientific results. But what is the story of the first explorations of this historic cave-- the human story? That story begins in 2007... After crawling around in viper-infested limestone caves in northern Saudi Arabia, it was time for a change and we decided to pay a visit to what I consider the most fascinating lava field in the whole country: Harrat Khaybar, home of the celebrated Black and White Volcanoes. I must confess we were partly motivated by hopes of finding a lava tube longer than Al Fahda Cave in Jordan which held the record for being the longest surveyed lava cave on the Arabian Peninsula (923.5 meters). May 15, 2007. This is Field Trip 62 for the Saudi Geological Survey Cave Unit, which now consists of only three members: Mahmoud Al-Shanti, Mohammed Moheisen and me. We are heading for a spot only 128 kms north of Medina, so we expect to be at the cave before dark. “I see the route includes 50 kms of bone-jarring, tire-slashing lava rubble,” I comment. “Yeah,” says Mahmoud. “It’s a piece of cake. I checked it out on Google Earth.” As we drive, we program co-ordinates into our GPS’s. After seven hours, we leave the highway and find ourselves in a vast field of black lava chunks criss-crossed by tracks running every which way. Our waypoints prove invaluable, though, and moments before sunset, we pull up next to a monster of a hole 89 meters long with passages heading off in opposite directions. We slap one another on the back: “Now, this is a real cave!” We had hoped to camp inside the cave, but it’s a 13 meter drop to the bottom of the collapse, reachable via a narrow trail that hugs one wall. Besides, our three drivers take one look at the big hole and declare that they are camping on the surface, even though the wind is howling like crazy. Putting up a tent under these circumstances is a real challenge. During the night the temperature drops to a comfortable 18 degrees Celsius.  Entrance

to the East (Workshop) Passage.

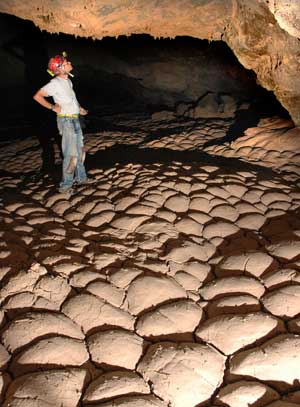

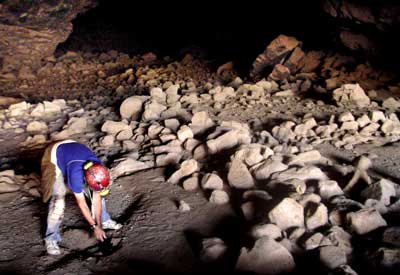

Next day we breakfast at the edge of our enormous hole. Off in the distance, 20 kilometers to the northeast, we can see the White Volcano, Jebel Bayda, gleaming in the sunlight. We are surprised to see Little Swifts (Apus affinis) darting in and out of the cave. We’re used to rock doves living in Saudi caves but this is the first time we see swifts. Do they use echolocation to find their way around in the dark as do those on the island of Mauritius? We decide to enter the east passage, surveying our way in. The sheer size of this lava tube is staggering. In one place it’s actually forty meters wide. Because the floor is mostly smooth, I get Mohammed to model for me. With the lens open, he walks across the width of the cave, lighting himself up with the flash every few paces.  Afterwards, Mohammed said he hated modeling for this picture. “Why?” I asked. “Because I had to shoot off that flash right in my eyes twelve times.” “But why didn’t you just close your eyes each time?” “Oooooh,” said Mohammed, “I never thought of that.” This cave would be impressive for its size alone, but inside we find all sorts of interesting things...  ...The floor, for example, is not flat but in most places takes the form of evenly-spaced “domes” of hard mud, about 20 cm in diameter and 6 cms in height. It’s like walking on tightly packed giant ball bearings.... According to an XRD lab report, these mounds contain mainly quartz,albite, kaolinite, nontronite, biotite, microcline and augite. It has been suggested that maybe the nontronite clay causes the swelling. ...We find wolf and hyena coprolites all over and plenty of bones. The walls are sometimes decorated with dazzling white gypsum or brownish calcite formations, including stalactites. In one place there is a huge block which seems magically suspended from the ceiling. Our survey covers around 50 meters between each station. Sometimes it’s farther than the practical range of our Disto laser survey tool. After 948.6 meters, we reach a second entrance and the end of the passage. We have beaten the Jordanian record and now have the longest surveyed lava tube on the Arabian Peninsula! Up on the surface, it’s beastly hot and the wind is still howling. Mohammed spots our camp in the distance and we walk back over the chunky lava. It was definitely easier to cover the same distance underground even though the cave has several curves in it. After lunch, I go back into the cave to take pictures. When I come out, it’s just getting dark. “Where are Mahmoud and Mohammed?” I ask the drivers, but they say they don’t know. By 8:00, we are all getting worried. Suddenly a light pops up over the edge of the big hole and Mahmoud’s head appears. Both he and Mohammed are panting and look agitated. “Wolves!” they shout... ...They scramble up to the surface and as tea is poured, they tell us their story. “We decided to survey the other (western) passage,” says Mahmoud. “After 341 meters, it got really dusty and stuffy and smelly. Rocky (the puppy Mahmoud adopted on our last cave trip) refused to go any further and seemed paralyzed with fear. There were all kinds of bones in this place and then we looked into an opening at the very end of the cave. It was full of wolf droppings, mostly fresh...  Human skull in situ in wolf den.

Radiocarbon dating later showed it to be around 150 years old. Photo by

Mahmoud Al-Shanti.

And that’s when I heard a kind of rumbling sound. I asked Mohammed if that was his stomach rumbling and he said, ‘It’s not me.’ Then we heard something moving around farther inside and suddenly there was this loud growl and a kind of roar and we high-tailed it out of there with me carrying Rocky in my arms. That den at the back is full of wolves!” Before going to bed, Mahmoud tells me he has a feeling that this cave was used by a lot of people in the past. We decide to spend some time the next day looking for signs of human habitation. Friday. No wind today. At 4:45 AM I hear Hamadi giving the pre-prayer wake-up call. This must have been exactly the right time to rise back when desert travel was limited to the cool morning hours, but I wonder how modern city folk (who like to stay up until the wee hours of the night) could possibly get their eyes open twenty minutes before sunrise. After breakfast we all go down into the pit. For the first time, I notice that certain spots on the basalt “stairway” we are using are highly polished. “Mahmoud is right,” I say to myself: an awful lot of people have walked down this path.”  Mohammed (arrow) on the narrow trail.

Basalt surface of the trail, polished by

the feet of how many past visitors?

I look for rock art on the pit walls, but I can’t tell whether the animals I see are products of my imagination or vestiges of some primitive artist’s masterpiece. We go into the East passage. I pound an iron rod into the caves dirt floor, which turns out to be 1.17 meters deep. This sediment has been deposited sometime during the cave’s three-million-year history. We speculate on what might lie buried beneath the floor’s surface. No excavations have ever been done in any of Saudi Arabia’s lava tubes, most of which have floors as thick as this one.  John Pint's primitive depth

gauge.

The Workshop We go around a big bend and approach survey station 5, which is 188 meters inside the cave. It is almost totally dark except for a faint glow from the entrance. The hard, smooth mounds cover the floor of the passage, which is eighteen meters wide... ...Mahmoud sits down on a flat-topped rock about 25 cms high and says, “John, come look at these.” He shows me two “sticks” of basalt which were lying at the base of the rock he’s sitting on. At first, these look like nothing else but fragments of rock to me, but I shine my light on the ground and find another and another and another, all about the same length and thickness. After we’ve found eight of these, I’m sure they can’t be “just rocks.”...  Mahmoud

with a few of the

basalt fragments, conveniently shaped to fit the human hand...

On close examination, we see each one has a convex and a concave side and in every case, one end of the “stick” is pointed. When held in your fist, your fingers fall into the concave groove. We look around a little more and find half-moon shaped pieces that fit nicely into your hand and have a very thin edge. These seem to be scraping tools while the others might be for gouging.  "Gouger."

Convex side

facing viewer.

"Scraper"

has very thin

edge and fits nicely in hand.

Hundreds of chips of basalt are scattered all over the ground, covered by a thin layer of mud. Only a few steps away we find two more flat-topped rocks convenient for sitting upon and each is surrounded by objects of the same shapes we have been looking at. “This is just like the obsidian workshops I saw in Mexico,” I tell Mahmoud. “All the pieces we are looking at are the rejects. The good stuff was carried out of the cave.” The Wolf Passage We walk back to the entrance and find that the drivers have lowered all their tea-making equipment straight down into the entrance by rope. After tea, we three cavers—plus Rocky the cave dog—head into the Wolf Passage which I haven’t seen yet.  The entrance to this side of the cave is spectacularly big. On top of the breakdown just inside the entrance we find a baby crow with a broken wing. Mahmoud immediately adopts the crow, as he did Rocky. This west passage has a flat floor with no mysterious mounds. It also has lava levees which the other passage doesn’t. At a certain point, we come upon lots of bones which look very old and a pile of feathers which look very recent. “Those feathers weren’t here yesterday,” says Mahmoud. It’s interesting that the predator brought the bird this far into the cave, where there’s no light at all. We go a little further and find a huge Ibex horn. At this point, Rocky the dog lies down on the floor and refuses to walk. A second later, Mahmoud spots two red eyes watching us from deeper inside the cave. We decide it’s time to leave. Mahmoud has his arms full carrying Rocky in one and the crow in the other. It—whatever—it is, does not follow us. Near dusk, the swifts return, swooping through the air like bats. Are they catching insects? We haven’t noticed any flying insects around here at all. Night falls. Along the edge of the pit we see flickers of fast-moving shapes. At first we assume it’s the swifts but we find they are large bats (well, larger than Asellia tridens, which we usually see). The bats fly fast, round and round along the walls in a wave-like pattern, “cresting” barely one meter above the lip. Next morning, we pack up to the shouting and banter of the drivers. Naturally the wind is howling like crazy, making it just as hard to take down my tent as it was to put it up. Everyone has cooperated to collect our trash for burning, but when I go off to answer nature’s call (a long walk is required) I see that the black lava is now dotted with white spots as far as the eye can see: a sea of Kleenexes! After our return to Jeddah, we email pictures of the basalt fragments we found to everyone we can think of. Replies come in: “Stone age tools? They’re fakes.” “Stone age tools? They’re geofacts not artifacts.” “Stone age tools? Yes, that’s what they are and they’re at least 600,000 years old.” Return to Umm Jirsan Two weeks later we’re on our way back to finish mapping the entire system, which includes three sections of lava tube and three collapses. This time the only cavers are Mahmoud and I and he is not in the best of shape, having badly sprained his back the previous night. During the drive, we plot the location of our cave on the geological map of Harrat Khaybar and discover that we can actually see the string of collapses we have been exploring. Our cave is in one of 40 "Whaleback Flows," which are slightly elevated areas above lava tubes, always punctuated with a number of big holes where the ceiling has fallen in... ...What’s exciting is that our survey of the cave confirms that there can be intact lava tubes between one hole and another. Since some of the Whaleback Flows are up to 17 kms long, it looks like there may be enough long lava tubes in Harrat Khaybar to satisfy an army of cave explorers.  Circle shows Jirsan collapses on map by

Roobol and Camp, 1991. Note many other much longer strings of holes

nearby. Map courtesy of Saudi Directorate General of Mineral Resources.

After a long drive from Jeddah, we reach Umm Jirsan at sunset. Before nine the next morning we are in the East Passage of the cave, examining the area where we found the basalt pieces shaped like hand axes and blades. We sketch the area, assign letters to different sectors and take photos. We look around for some item that shows clear signs of having been worked, but only find more of the same: pieces of basalt that fit nicely in the hand and are pointed at one end. Assuming that the archeologists we have consulted are right and none of these fragments have been chipped or worked in any way, the fact remains that only in this part of the cave do we find a concentration of tool-shaped fragments. It could be that ancient people scoured the cave for basalt fragments useful for gouging and scraping, sorted them out the spot we call The Workshop and then left the cave with the best pieces. Investigation of more lava tubes in Harrat Khaybar might clarify this business. Strings of collapses shown on the geological map indicate there should be caves ten times longer than Jirsan. We decide we’ve had enough of amateur archeology and pull out the tape recorder. We walk through the cave and Mahmoud describes the geology of what we see. This will later accompany our map of Umm Jirsan in a report. This technique allows us to focus our attention entirely on the features of the cave and I spot some things I completely missed when we were surveying, for example, lava levees on both sides of the far end of the passage and flat wasps’ nests made of mud all over the walls at the other entrance. We also spot hundreds of fox tracks and the curvy lines left by a couple of snakes. Fortunately, we run into only a few wasps and no snakes, so we survey our way for 56 meters across a collapse dominated by a Buzzing Tree. I assume it is bees doing the buzzing and keep my distance, but Mahmoud discovers they are flies.  The other end of the

Workshop Passage. We see signs of ancient walls. Photo by Mahmoud

Al-Shanti

. This brings us to the third covered section of this lava tube system: a cave only 28 meters long with a man-made stone wall (in pretty good shape) stretching completely across it. Blast furnace temperatures welcome us when we get out of the cave, but we decide to walk back to camp over the surface in order to have a look at the places where water leaks down into the lava tube. We are delighted that our survey has extended the length of the cave system to 1481.2 meters. As soon as we arrive at our camp, of course, we go straight back into the cave and its pleasant environment of 21° C and 55% humidity and our drivers waiting for us with cool drinks and (what else?) chicken kabsa. Detail of our map of Umm Jirsan Cave

System. Click on this image to see the complete map.

After lunch we all go over to the Wolf Passage. Mahmoud and the drivers go all the way to the far end of the cave and bring back a human skull, fragments of two more skulls which look like they’ve been used as bowls, a very thick bone and a springy curved stick made of very hard wood...  From left to right the ages of the three

skull parts are: 150 years, 3410 years and 4040 years before present.

This large bone which appears not to have

come from a camel, is 2285 years old.

All these items were found on the surface of the meter-thick dirt floor. Much older bones may be buried underneath. ...I take pictures of the spectacular Wolf Passage entrance and find a small swift’s nest on the floor. Woven into it are many strands of green plastic that look like they’ve been unraveled from a feed sack or tarp. At 7:00 Pm we exit the collapse and collapse. There’s a slight breeze and it feels quite pleasant as we sit around the fire under the slightly fuller moon. Since we’ve been on the move all day long, we’re all hungry and Hamadi decides to make his famous barbecue chicken. It’s so good that we all decide Hamadi should open a restaurant. “OK,” says Hamadi, “I will open a restaurant with Abu Adel… and Sa’ad will be the dishwasher.” That leads us to the subject of how each person has some special talent. “All except Sa’ad” says Hamadi, joking. These two guys have been pulling each other’s leg for all the years I’ve known them. I intervene: “No, no. Sa’ad has a special talent too,” I state, obviously with Mahmoud’s help as translator. “What could that be?” they ask. “Why he’s the world’s greatest story teller,” I say, reminding them of how he pulled the wool over my eyes exactly one month earlier when we found a wide mud flat in the far north and he convinced me he used to play football there with the Beni Hallal, a legendary tribe that hasn’t been seen for a thousand years. We leave Umm Jirsan Cave System convinced that Saudi Arabia’s Harrat Khaybar is, indeed, the most promising caving frontier in the Middle East and perhaps one of the most important in the world.  Text and Photos © 2024 by John & Susy Pint unless otherwise indicated. |