|

By John Pint

In 2009 I heard rumors that a new

university had opened its doors in Saudi Arabia. It was said that King

Abdullah University of Science and Technology (KAUST) was vibrant,

dynamic, staffed by the world’s greatest scientists teaching the

world’s most brilliant students, a truly international university which

its founder, King Abdullah, Arabia’s reigning monarch, envisioned as “a

bridge between people and cultures…and a beacon for peace, hope and

reconciliation.” In 2009 I heard rumors that a new

university had opened its doors in Saudi Arabia. It was said that King

Abdullah University of Science and Technology (KAUST) was vibrant,

dynamic, staffed by the world’s greatest scientists teaching the

world’s most brilliant students, a truly international university which

its founder, King Abdullah, Arabia’s reigning monarch, envisioned as “a

bridge between people and cultures…and a beacon for peace, hope and

reconciliation.”

Naturally I contacted KAUST, suggesting that Saudi Arabia’s caves—many

of which are over a million years old—would be ideal natural

laboratories for KAUST researchers to carry out projects and, quite

likely, discover new species of cave life while uncovering bones and

artifacts thousands of years old.

“We’ve barely opened our doors,” replied my KAUST contact, Dr. Sigurjon

Jonsson, a geophysicist from Iceland. “Give us a few years to get

organized.”

Finally, in 2012, I got the green light. “Come tell us about the

caves,” said Sigurjon, “during our Winter Enrichment Program in 2013.”

This WEP, I quickly learned, was an annual three-week event in which

students could attend presentations on almost any subject by the likes

of environmental advocate Philippe Cousteau, Swiss astronaut Claude

Nicollier and Egyptian archaeologist Zaki Hawass…and, this year, yours

truly, giving not only a course, but leading a field trip to a Saudi

lava tube as well.

So now, on January 10, 2013, I find myself in the middle of a 30-hour

journey from Guadalajara, Mexico to Thuwal, a fishing village on the

coast of the Red Seal, amazingly transformed into an enormous

university campus which is practically an independent city. KAUST has

kindly treated me to business class on Lufthansa Airlines and I am

having the time of my life, playing with my mechanized seat, which

converts to a “near bed” at the push of a button, but with vibrations,

whirrs and clunks suggesting this device is something between a

barber’s chair, a Transformer Robot and a trash compactor.

A mere 30 hours later, I am installed in a suite at the university’s

guest house. I step out onto my balcony and behold a scene right out of

the Arabian Nights: a vast promenade lined with palm trees, a majestic

mosque at one end and the glittering Red Sea in the distance. What a

place!

The next morning, jet

lag works in my favor, helping me to rise early and off I go to the

university dining hall, a ten-minute walk that immediately orientates

me to the world in which I have been plunged. Soaring structures of

extraordinary architectural beauty rise above me while hundreds of

students and professors on bicycles criss-cross my path and shoot past

me. This is a new-millennium university—and it’s co-educational: almost

as many women as men pass me on their bikes. Posters, billboards and

electronic signs remind me that it’s WEP time: Philippe Cousteau will

talk about the oceans, historian Sami Nawar will take us on a journey

through old Jeddah. I marvel at all this. These students come from

China, Brazil, Indonesia, Mexico and dozens of other countries,

including, of course, Saudi Arabia and the Middle East.

The students are all post-graduates and they came here to specialize in

their own careers, but this WEP is exposing them to widely diverse,

fascinating subjects well beyond their fields of expertise. This is

dangerous. What could happen? KAUST could easily give birth to a new

Renaissance Man…and Woman! WEP could turn half these cyclists into

Leonardo Da Vincis! My God, this university might even accomplish what

King Abdullah says he’s been dreaming about for years: a new birth of

scientific enlightenment in the Middle East, a flashback to those

fabled times when Arabs gave us Algebra, Alchemy and Astronomy and were

the only ones in the world who bothered to preserve the teachings of

Aristotle.

I muse on all these things while preparing my course on Limestone and

Lava Caves and the Secrets of Cave Photography. I am amazed that around

100 students show up for each of my PowerPoint presentations...

...I show them beautiful

caves decorated with gorgeous stalactites and stalagmites, ideal for

transformation into tourist caves.

I list the many artifacts and bones we have found, including part of a

human skull over 4,000 years old. I point out that there are at least 40

unexplored lava tubes located only 300 or so kilometers north

of KAUST, many of them up to 25 kilometers in length, housing who knows

what treasures placed there by early man 70,000 years ago. I casually

mention that no biologist, microbiologist or archaeologist has ever

studied these ancient caves, located so close to the very cradle of

humanity.

And now it is time for our field trip to Hibashi Cave. “Only 20

students can go,” Sigurjon tells me, “but there are over 100 on the

waiting list.”

Hibashi Cave lies 225 kilometers east of Mecca in the middle of a wide,

inhospitable lava field. It is probably the most celebrated cave in

Saudi Arabia today, as it was placed on the list of the World’s Ten

Most Important Lava Caves, due to the abundance of rare minerals found

inside it. On top of that, NASA collaborators at MIT are using Hibashi

as a model for a Martian lava tube, due to the meter-thick layer of

fine, powdery silt covering every inch of its floor. It’s this silt or

loess that forced us to limit the number of visitors to twenty-some. No

matter how carefully you move, this 5,000-year-old “dust of ages” soon

fills the air.

On January 16, the lucky twenty plus a few of us leaders meet after my

last course, ready to board our bus to the town of Taif and (tomorrow)

Hibashi Cave. Amazingly, our small group represents ten different

nations—we are a KAUST in miniature.

The bus appears on time, but, alas, with a window newly smashed by our

driver while making a tight turn.

“We’ll have to wait for a new bus,” announces Sigurjon. So we start our

journey 90 minutes late, but after an hour on the road, a student

shouts from the back of the bus: “Another window is about to fall off!”

Ah yes, no matter what sophisticated project you

launch, whether in Saudi Arabia or Mexico, somewhere deep in the

infrastructure you just might run into primitive conditions which—as in

this case—usually respond well to primitive solutions. “Somebody hand

me the duct tape!” shouts Sigurjon as he climbs on top of a land

cruiser our driver has dangerously parked next to the bus, right in a

lane of fast-moving traffic. Ah yes, no matter what sophisticated project you

launch, whether in Saudi Arabia or Mexico, somewhere deep in the

infrastructure you just might run into primitive conditions which—as in

this case—usually respond well to primitive solutions. “Somebody hand

me the duct tape!” shouts Sigurjon as he climbs on top of a land

cruiser our driver has dangerously parked next to the bus, right in a

lane of fast-moving traffic.

As usual, duct tape saves the day, and in a few hours we are in Taif,

relaxing in the stunning Awaliv Hotel, where, the next morning, we

watch the sunrise from a revolving restaurant on the 29th floor. What a

view!

Our bus has been replaced by a third one with all of its windows

intact. We speed east through wide expanses of flat, volcanic rubble

toward a spot on the road where six land cruisers are waiting to

transport us over ten kilometers of rough, sandy tracks heading every

which way through tire-eating lava. I can only hope that the track I

recorded on my GPS nine years ago will actually bring us to Hibashi

Cave.

Suddenly there is a round of applause as our Bedu driver pulls up next

to a great, black gaping maw 14 meters wide. Hibashi Cave at last!

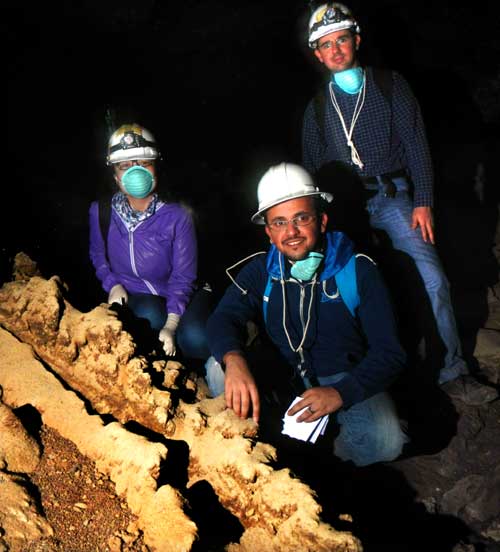

Sigurjon

passes out helmets, lights and face masks and soon we are all 26 meters

beneath the surface inside a passage darker than the darkest night,

decorated with lava stalactites and stalagmites and filled with animal

and human bones carried into the cave over the ages by hyenas, wolves

and foxes. The students have all chosen projects to carry out

underground, such as measuring the depth of the silt and collecting

samples of the cave’s soil, dove and bat guano and thousands of

perfectly preserved coprolites scattered throughout the cave’s 581

meters of passages. To see photos of these enthusiastic young

explorers in awesome Hibashi Cave, just amble over to

KAUST

Students Explore Hibashi Cave.

To

my great relief, a head count proves we have left no one inside the

cave and after a tasty meal of chicken kabsa, we begin the long drive

back to Jeddah and Thuwal.

Two nights later, Philippe Cousteau,

who was raised by his grandfather, Jacques Cousteau, addresses a packed

auditorium at KAUST. He tells us about the “osteoporosis of the

oceans,” the result of carbon being absorbed by sea water, spelling

doom for shellfish, and he discusses successful solutions to oceanic

problems, such as Mexico’s Cabo Pulmo, which he calls “the best-managed

Marine Protection Area in the world.” And Cousteau also has a word to

say about KAUST, which invited him—and me, too—to participate in its

Winter Enrichment Program: “What an absolutely spectacular place!” he

says. “KAUST is a hotbed of ideas and potential.” Two nights later, Philippe Cousteau,

who was raised by his grandfather, Jacques Cousteau, addresses a packed

auditorium at KAUST. He tells us about the “osteoporosis of the

oceans,” the result of carbon being absorbed by sea water, spelling

doom for shellfish, and he discusses successful solutions to oceanic

problems, such as Mexico’s Cabo Pulmo, which he calls “the best-managed

Marine Protection Area in the world.” And Cousteau also has a word to

say about KAUST, which invited him—and me, too—to participate in its

Winter Enrichment Program: “What an absolutely spectacular place!” he

says. “KAUST is a hotbed of ideas and potential.”

I can only echo those words. King Abdullah’s dream seems to be turning

into reality.

|