|

© 2005 by John and Susy Pint -- Updated September, 2013

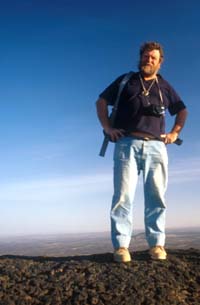

John Roobol is the very

picture of a sea-faring man. On his weathered face are written tales of

heroic struggles against the merciless elements and

through his great frizzled beard you can almost hear him shouting to

his bone-weary crew, “Belay the hatches and be quick about it, laddies!”

One day I looked up from my desk to see the large frame of this imposing

Welshman filling the doorway (and believe me, when Roobol is in your

doorway, no one else is getting in or out!).

Well, I soon discovered that John Roobol is, indeed, a sea-faring man,

but

the seas he really knows best are the seas of lava which fill much of

western Saudi Arabia.

“So yer interested in lava tubes, are ye?” he boomed. And that brief

encounter explains how we Saudi cavers ended up spending a week

camped alongside Jebel Hil, deep inside Harrat Kishb, a veritable sea of

rough black lava that is exceedingly difficult to traverse.

While flying over the crater of Jebel Hil in a helicopter, Roobol had

spotted a straight line of round collapses leading away from Jebel Hil

in a

westerly direction. It had to be a large lava tube and there was no

telling

how long it might turn out to be.

Upon presenting the idea of searching for lava tubes in the harrats,

people

who knew these nearly inaccessible areas told me we were

crazy. “Those

lava

fields are full of large, deadly snakes and, at night, if you light a

lantern at your campsite, you’ll see big black scorpions running

towards it

in minutes. On top of that, the place is thick with

mosquitoes these

days.”

TO

THE LAND OF SNAKES AND

SCORPIONS

...Our hopes for success on this mission were greatly

bolstered by a bit of pure luck. By sheer co-incidence, John had been

handed

a set of photographs, taken by a hunter somewhere in Kishb but with no

clue

as to exactly where.

Several imposing lava-tube entrances were shown and proved

that

large walk-in caves were waiting for us… if we could cross those

“exceedingly difficult” lava beds.

This, it was decided, was a fine place to camp. “The strong breeze will

keep

away the mosquitoes,” said Mahmoud. Apparently there were no

sleepwalkers in

the group and no-one minded camping four meters from the brink of a deep

chasm.

THE

FLYING TENT OF WAHBAH CRATER

Susy

and I chose a spot a little

farther from the edge. We put down our ground cloth, set up the tent

and turned our backs to assemble the

tent fly. Only two seconds later we turned around to discover – to our

dismay – that our tent was gone!

“Where’s the tent?” I shouted, suddenly in shock.

Now, my night vision has diminished with the passing years, but Susy

could just make out our tent bouncing along the ground in the distance,

for the

moment, (thank God) not in the direction of the crater. We took off

like saluqis and

caught up with the tent, but while trying to get hold of it, I slipped

on the loose gravel and ended up with a bloody knee, a major handicap

if you’re

planning to spend the next four days caving.

A bit later, someone noticed that one of the (new) cars had a flat tire

and the drivers took it back to the town of Oomadoom for repair. It had

four

punctures in it and we hadn’t even approached the lava fields!

STUCK

For hours we worked our way through great black

blankets of volcanic rubble,

broken by occasional smooth, flat areas dotted with acacia trees. In

one of

them we found “the only thick sand I’ve ever seen around here,”

according

to

John Roobol and, of course, we managed to get our ancient pickup truck

hopelessly stuck in it. After doing our best to burn out the engine, we

finally resorted to the infallible way to get out of the sand: we let

the

air in our tires down to 15 lbs, drove right out, and then spent a very

long

time pumping the air back in.

At last we found ourselves on top of a somewhat flat place alongside

Jebel

Hil and - lo and behold! – while searching for a good camping spot, we

spotted a dark patch on a low wall. This proved to be a vertical cave

entrance about 20 meters high. Leaning over the edge, we could see

spacious

tunnels going off in opposite directions. Our first lava tube!

We set up camp nearby, ate and decided to go have a look at the series

of

holes proceeding from Jebel Hil.

A ten-minute drive brought us to a lookout point right beside the

volcano.

We had a magnificent view of the flat plain below us but, alas,

couldn’t see

the line of collapses from this position.

“Ye can see everything from the top of volcano,” remarked John Roobol,

who

(as is his way) immediately began climbing. Well, it was about 4:45 and

it

looked like we could just make it to the top and back before sunset, so

we

all followed him.

ROOBOLING

UP THE VOLCANO

Ah, but this “Hil” is not a “hill” up which one can merrily prance while

filling the air with the sound of music! No, I swear the sides of this

volcano are as close to 90 degrees as I would ever want to get and only

20

meters or so on the way up you could see almost every member of the

group

hanging onto some tiny knob of rock, the only thing solid in a sea of

loose

scoria, ALMOST everyone, that is, because Abdulrahman, the biggest guy

among

us (excluding JR, of course) was dashing up that slippery mountain like

a rabbit.

...It seemed as if an eternity passed before I made it. After catching

my breath, I began to take pictures of the magnificent interior of the

crater,

in which you could see a wide, flat “ledge” which had once been the

surface of a lake of lava, and the collapsed hole through which lava

had flowed

into what must be a mighty impressive lava tube.

And then I heard a female voice. I couldn’t believe it! Susy’s head

popped over the edge! Later she said, “When I saw that YOU had made it,

I knew that

I could too.” Now tell me, is this a compliment?

As we walked along the

crater’s narrow rim, John Roobol enthusiastically described Jebel Hil’s

geology and history. Meanwhile, sunset was approaching and we were

wondering just how we were going to get back down. “Well, certainly not

the way we came up,” said John. “It’s much too steep. We’ll go down

another

way.”

We continued walking a lot farther and then checked

the slope. It was even steeper than where we had climbed up and 100%

scree. Besides, it looked like

there was a sheer drop about halfway down.

“John, how did you go down last time?”

“Well, now, the last time I was here, you may recall, was by

helicopter.”

“You mean you’ve never climbed down before?”

“Nor up.”

BURNT

BOTTOMS

This explains how six apparently rational beings sat down on a nearly

vertical slope and tried to slide down on their posteriors, hoping they

wouldn’t make the small mistake that could start them tumbling down the

volcanoside like snowballs.

Well, most of us ended up shredding the seat of our pants, all except

John

Roobol, who used his rucksack as a sled and came out of it with his

backside unscathed.

Somehow we all survived and may even have achieved fame as the first

brave souls to have climbed and butt-tobogganed down Jebel Hil.

LOST

IN THE DARK

That night Hamadi discovered a snake, 1.5 meters long and the color of

silver, near our camp, after which the drivers decided to sleep inside

the

Land Cruisers, instead of under the stars, as is their usual want.

The following morning,

Monday, we sent our ancient, decrepit, pickup truck off to Oomadoom for

supplies. I figured it had a 10% chance of making this

voyage and that we’d be hunting Hamadi’s snake for food by the next day.

Unfazed by our plight, as befits intrepid and tenacious geologists, we

spent the day trapsing over kilometers of harrat, all spread out in a

long line,

hoping to find those walk-in lava tubes in the photos. What we did find

were lots of olivine gems and even a garnet. Finally, we resorted to

hunting up

some bedus who led us to an area where the hills resembled those in the

background of the famous snapshots.

Here, at last, we found three fine caves, two of them walk-in and one

vertical, a 7 meter deep collapse with passages going off in two

directions.

We strolled far into the walk-in cave and agreed we would survey it

next day. We took the coordinates and headed back to camp where we

discovered

that our pickup had failed to arrive. Scraping together the last of our

provisions and even opening our emergency cans of beans, we shared a

meager

meal, discussing the strong possibility of having to abort our mission

the following morning.

Impossible as it seems, we spotted car lights around 8 PM. A half-hour

later,

the pickup arrived to a hero’s welcome. They had gotten lost on the way

back

and had spent all afternoon working their way towards Jebel Hil. But

they

made it and bought us an extra day.

A

BED THAT EATS SHOES

On Tuesday morning we split into two groups. Four valiant souls went to

hunt

for the lava tube holes below Jebel Hil. They trudged some 12 kms over a

very rough lava bed, visiting each entrance, noting depth, diameter and

amount of collapse, etc. Commented Mahmoud and Abdullah Eissa:

“It was prickly “Aa” lava most of the time –except close to the lava tube -- with irregular, loose chunks ready to break your ankle mixed with thin pieces ready to collapse under your weight. John Roobol kept reminding us to be careful with every step because ‘We could all die out here.’ ”

They returned, not dead, but dead tired, around 5 PM, having lost

considerable shoe leather.

|

|

|

I was in group two, whose mission was to map the caves found yesterday.

I

“guided” our driver “”Eagle-eye Sa’ad” to the site using GPS

coordinates, a

method of navigation Sa’ad did not approve of at all. On the way back he

asked me not to use the GPS and he got us home in half the time, by an

entirely different route!

FIRST

LAVA TUBE SURVEY

Upon reaching the entrance to the first cave, I surprised my three Saudi

trainees by announcing that THEY would carry out the

first survey of a Saudi lava tube. Susy and I would merely assist.

We then spent a while practicing how to use the compass, clinometer and

Disto digital measuring device as well as how to fill in the

B&B survey

book.

This lava tube is about four meters high, 157 meters long and easy

walking all the way. About half-way in, we began to see small

basalt stalactites which had once been drops of molten lava. According

to John Roobol, the cave

was 1000 degrees, walls glowing red, when this happened. Seventy-five

meters

from the entrance we found a raised side chamber with what appear to be

very

old hyena, wolf and who-knows-what droppings, surrounded by bones.

Exiting this cave, I asked the surveyors what they wanted to name it.

“Kahf

Mut’eb,” they told me. These words mean “very difficult

cave.” Now,

this

was a flat, smooth easy-walkin’ single passage. So what would

you name the kind where you have to take readings

while lying on your belly in a tight crawlway half full of a gooey

mixture of guano, mud and bat pee?

Worn out and aching for lunch, the survey crew

preferred

to stand by and let me have all the pleasure of exploring the

7-meter-deep

hole just a short walk away.

GHOSTLY

CAVE

...I walked over to the one heading west.

The entrance to it was long and low. I bent over

and peeked inside. In

the half-light beyond, I could see a large chamber filled with figures.

It

was as if I had surprised a gathering of skinny goblins and they had

immediately turned to stone.

Slowly – and I do mean slowly! – I stepped into the room. “These statues

look like stalagmites,” I thought to myself, “but there are no

stalactites

above them, and, besides, I’m in a lava tube, not a limestone cave."

On closer examination I found that these strange

figures were made of bird droppings. There must have been fifty of them

in there, the tallest standing

five feet (1.52 m). Now, one rock dove had flown out of that room when

I entered, but what had happened to all the others?

I also wondered how old those guanomites were, as I made my way through

them, deeper into the cave. The floor

consisted of fine, powdery dirt

covered with a thin layer of bird guano. It crunched like snow. At one

point, I broke

through the crust and my foot sank down 20 cms. This was a

new sort of cave experience for me and I regret I was in a hurry and

couldn’t

examine

the place better.

I followed this passage to its end where I found stuffy air and a

handful of very small bats. Then I counted off 180 paces back to

daylight.

The passage going the opposite way was also interesting. Only a few

guanomites, but they were inside a huge room maybe 50 meters around. A

large

part of the wall and roof were covered with a crispy crust of a pure

white mineral which is not calcite. At the end of this large room there

was a

passage heading east. I followed it a bit and it just kept going. Good

reason for a return trip, I figured and headed back to the cable ladder.

Strong winds tested our tents all night long. The Eurekas won out over

Coleman and even did better than our mighty North Face! Next morning we

packed up and headed for Oomadoom. However, we got ourselves good and

lost on the way. Fortunately, we found some local bedus who were

unstintingly

generous (as they inevitably are). One of them jumped in his truck and

led us for what seemed hours to a wide track.

Although this track did not seem at all familiar, it led us out of the

harrat. However, instead of reaching Oomadoom, we ended up in a town

called

Marran. No matter, we were on black top again and on our way back to

Jeddah.

And we hadn’t seen a single snake, scorpion or even mosquito inside the

wonderful lava tubes of Harrat

Kishb.

John Pint

FOR MORE IMAGES

OF

HARRAT KISHB

GO TO

THE PICTURE

GALLERY!