Updated September, 2013

Sketches of caves located in Saudi Arabia have probably been made for centuries, but the production of accurate cave maps based on the use of survey compasses, measuring tapes and clinometers is a very recent development.

In the summer of 2007, Saudi Geological Survey published its first collection of cave maps, entitled:

Maps of caves surveyed by Saudi Geological Survey, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia: Saudi Geological Survey Data-File Report SGS-DF-2005-14, 59 p, 58 figs.

This

data file brings together maps and sketches of twelve limestone caves and seven

lava tubes explored by the Saudi Geological Survey Cave Unit during the years

2000-2004. One of these caves was found within the city limits of Riyadh; four

of the caves are located on the As Sulb Plateau; seven are found in the northern

regions of the Kingdom and the seven lava caves are located in Harrats Khaybar,

Ithnayn, Kishb and Nawasif-Buqum.

| The nineteen cave maps and sketches in this collection represent only a few of the many caves located and/or explored by the SGS Cave Unit between 2000 and 2004 and it is expected that more collections of cave maps and sketches, based on these explorations, will be compiled and published in the future.

This report can be downloaded as a PDF file (4.l megabytes) from this website.

|

|

A

Brief History of Cave Mapping in Saudi Arabia

In the late 1930s, geologist and later CEO of Aramco, Tom Barger, sketched the

interior of some dahls located near Ma’aqala in the karst of the Summan Plateau

(Barger, 2003).

In 1968 German divers published a sketch of Ayn Khudud, the largest spring in

the Al Hasa Oasis. (Al-Sayari & Zötl, 1978).

In 1976, H. Hötzl & V. Maurin published a map of Ghar An Nashab, a series of

30m-high, narrow, joint-controlled fissures containing 1.5 kms of passages.

Their survey was carried out using tape, compass and clinometer readings and may

be the first “professional” cave map ever made in Saudi Arabia. For many years

Ghar An Nashab (also called Al Qara Cave), located near Hofuf in Al Hasa, has

been Saudi Arabia’s best known (and perhaps only) Show Cave. (Al-Sayari &

Zötl,1978).

In 1983, Bruce Davis of the U.S. National Speleogical Society published sketches

of several caves including Dahl Sabsab (Davis, 1983). Years later, the accuracy

of this Sabsab sketch was commended by geologist Greg Gregory after mapping the

cave with compass and tape (Gregory, 2001).

|

Perhaps the first attempt to map a lava tube in Saudi Arabia was made by Mamdoah

Al-Rashid who used a 50m-long tape to measure the length of Kahf Al Shuwaymis.

The date of this event is not recorded, nor is there any reference to the use of

a compass, but Mr. Rashid’s calculation of the cave’s length (500 m) comes very

close to the length of 530 m measured in a recent BCRA grade 3C survey (Rashid,

2002). If the length of side passages (30 m) is removed from the total, Mr.

Rashid’s results are exactly on the mark.

|

|

|

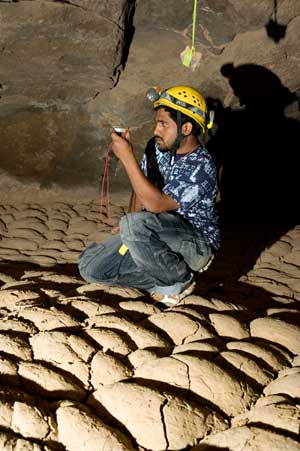

Perhaps the most important Saudi cave studied in recent times is Ghar Al Hibashi,

a lava tube located in Harrat Nawasif-Buqum and surveyed by the SGS Cave Unit.

The map of Hibashi Cave indicates the locations where 19 cave minerals—many very

rare—were found, along with the age of a human skull found in the cave and of

samples taken from the thick carpet of loess covering the floor. In 2004 Hibashi

Cave was named one of the ten most important lava caves in the world, for its

mineral content and is presently being used by NASA contractors as a model for

the lava tubes of Mars (Pint et al, 2005).

|

|

The Challenge of Surveying Caves in

Saudi Arabia

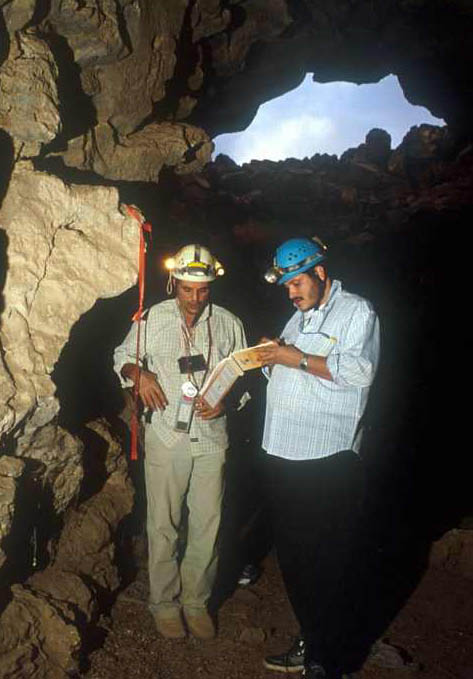

Mapping desert caves exposes the surveyor to certain difficulties and dangers peculiar to the underground environment. Simply entering the cave may require a rappel into a black void of considerable depth or a climb down a swinging cable ladder only centimeters away from a delicately balanced, ten-ton boulder which could shift at any moment. Darkness awaits the surveyor at the bottom, forcing him or her to squint through the sights in his or her instruments at a torch-lit target shrouded in inky blackness. In Saudi caves, a temperature of 25° and humidity as high as 97% might add to the difficulty of taking accurate measurements. Extremely dry caves, on the other hand, may have over a meter of loess or very fine powder covering the floor, producing choking clouds of dust at every step...

|

...To make matters worse, a walking passageway may eventually turn

into a low crawlway which will require a separate station every time it twists

left or right. The surveyor must take notes and measurements while

belly-crawling through mud, sand, desiccated hyena scat, water, bat guano, bat

urine or a combination of all six. On top of that, in the caves of northern and

western Saudi Arabia there is a distinct possibility that he or she will find a

hungry wolf waiting at the end of the crawlway. ...and if the wolf doesn't get you, wait until you step out of the cool cave into the 120 °F heat of a sizzling day in June! John Pint roasting outside Collapse Entrance 3 to Umm Jirsan Cave. Photo by M. Al-Shanti. |

|

John Pint

REFERENCES:

Al-Sayari, S.S. and Zötl, J.G., editors, 1978, Quaternary Period in Saudi

Arabia. Springer-Verlag, Wein, Austria.

Barger, T., 2003, personal communication of Tim Barger to John Pint.

Benischke, R., Fuchs, G. Weissensteiner, V., 1997, Speleological Investigations

in Saudi Arabia, Proceedings of the 12th International Congress of Speleology,

La Chaux-de-Fonds, Switzerland, pp. 10-17, VIII, 1997, Natural History Museum,

City of Geneva, Switzerland, Swiss Speleological Society (SSS/SGH), Symposium 8:

Karst Geomorphology, 425-428.

Davis, B., 1983, Voids Between the Dunes, NSS News, November: National

Speleological Society, p. 278-284.

Gregory, A., 2001, “DGS Caving Field Trip," The Oil Drop, Vol. 13, Issue 7,

Sept. 2001: Dhahran Geoscience Society, p. 3-4.

Peters, D., Pint, J. and Kremla, N., 1990, Karst Landforms in the Kingdom of

Saudi Arabia, NSS Bulletin, June 1990: National Speleological Society, pp. 21-32

Pint, J., 2003, The Desert Caves of Saudi Arabia: Stacey International, London,

120 p.

Pint, J.J., Al-Shanti, M.A., Al-Juaid, A.J., Al-Amoudi, S.A., and Forti, P.,

2005, Ghar al Hibashi Harrat Nawasif/Al Buqum, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, with the

collaboration of R. Akbar, P. Vincent, S. Kempe, P. Boston, F. Kattan, E. Galli,

A. Rossi and S. Pint: Saudi Geological Survey Open-File Report SGS-OF-2004-12,

68 p., 43 figs, 1 table, 2 app., 1 plate.

Rashid, M., 2002, Personal Communication to J. Pint.