(first published in the Guadalajara Reporter, August 11, 2016)

By John Pint

In

1894, a man living near the famed ruins of Teotihuácan, 50 kilometers

from Modern Mexico City, discovered a small, preHispanic house whose

walls were covered with beautifully colored murals. The place was

called Teopancaxco or “La Casa de Barrios.” The paintings were the

first of their kind found at Teotihuácan and visitors considered them

spectacular.

Weather and time eventually did their damage to the

murals and today we would have little idea of how they once looked if

it were not for an extraordinary Englishwoman named Adela Breton who

had fallen in love with Mexico's ruins and who painstakingly reproduced

these murals as watercolors. Mary Frech, author of Adela Breton, a

Victorian Artist amid Mexico's Ruins, says, quoting James Langley:

Watercolor painting of the mural at la Casa de Barrios, Teopancaxco, by British explorer Adela Breton “Adela 'made the

most comprehensive record of the murals at Teopancaxco. Her re-creation

of the colours of the murals is unsurpassed compared with the few

colour reproductions available, and thus constitutes an irreplaceable

memorial of the now destroyed masterpieces.'”

What was an unmarried Victorian gentlewoman doing in Mexico before the

turn of the century, 5500 miles from home?

Exploring,

painting, sketching, measuring and photographing not only Mexico's

best-known archaeological sites like those at Chichen Itza, but, it

seems, even obscure ruins from the extensive Teuchitlán Tradition of

western Mexico which, it was generally believed, were unheard of before

the late, great Phil Weigand gazed upon the Guachimontones in 1969.

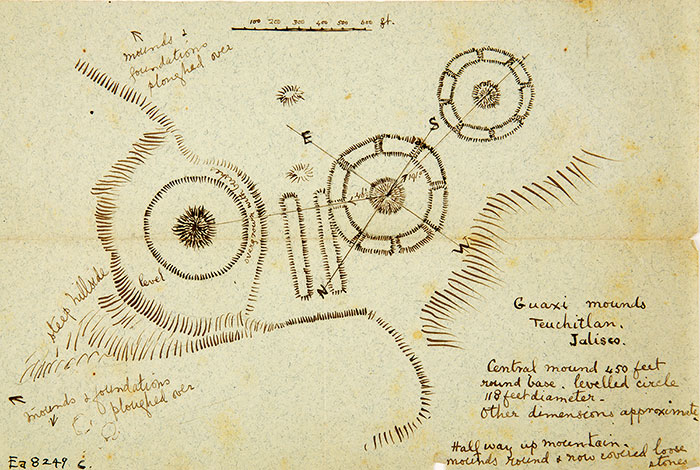

Proof

of Adela Breton's keen observations in Jalisco came to light recently

when the Museum of Bristol published Breton's sketches of the now

famous Circular Pyramids of Teuchitlán.

“Accurate drawings of the Guachimontones in 1896?” exclaimed

archaeologist Rodrigo Esparza. “That's amazing!”

Adela Breton's 1896 sketch of the three principal Guachimontones near Teuchitlán. Click on the image for better resolution. Even

more amazing was the discovery, again thanks to the Bristol Museum,

that Adela Breton had taken the first known photographs of the three

largest “Guaxi mounds” as she labeled them.

Did Miss Breton

publish anything related to the Guachimontones? The answer is

yes, but apparently only a few words. Here is what she says in a paper

delivered at the International Congress of Americanists in 1902:

“Teuchitlán

is a small town at the foot of a long spur of [Tequila] volcano... At

Teuchitlán, obsidian rejects are thickly strewn over a great extent of

ground. In addition to the obsidian, it has a most

interesting

ancient site on the summit of the hill, and the remarkable mounds and

circles called Huaerchi Monton half way up.”

While in Jalisco,

Miss Breton's resourceful guide Pablo Solorio somehow learned that a

mound housing an untouched tomb had been discovered near Etzatlán and

had recently been opened. Adela went to the Mound of Guadalupe and

gives us what is probably the first description of the unearthing of a

burial site in western Mexico. “Unfortunately,” she reported, “there

was no skilled supervision, no data were secured, and most of the

figures were broken.”

Fortunately, however, the resourceful

Adela was on hand and recorded, according to Mary Frech, that “the

mound was about forty feet high and held a burial with pots, jewelry,

clay 'portrait' figures ranging from twelve to twenty inches tall and

other artifacts.” Of course she sketched a number of those broken

figures and even photographed the Mound of Guadalupe, of which today

little is left to see.

Adela Catherine Breton was born in London

in 1849.After the death of both her parents, she was “easily convinced”

by pioneer in archaeological techniques Alfred Maudslay to travel to

Chichén Itzá to make sketches which would allow Maudslay to check the

accuracy of his own drawings, before publishing his Biologia

Centrali-Americana. Thus began her curious career as an archaeological

artist.

Adela Catherine Breton was born in London

in 1849.After the death of both her parents, she was “easily convinced”

by pioneer in archaeological techniques Alfred Maudslay to travel to

Chichén Itzá to make sketches which would allow Maudslay to check the

accuracy of his own drawings, before publishing his Biologia

Centrali-Americana. Thus began her curious career as an archaeological

artist.

According to Matt Williams of the Bath Royal Literary & Scientific Institution,

Adela “developed into a world-renowned archaeological copyist thanks to

her drawings of friezes, carved reliefs, painted plasters and other

cultural treasures – some of which are now the only records that remain

of items long since lost to vandalism and decay.”

Williams says

Adela traveled hard and wrote, “I used to live chiefly on air and a few

peanuts for the long riding journeys — 30 miles without any breakfast.”

"Adela

chose not to marry,” he adds, “as it was the only thing that guaranteed

a woman's independence in those days. She wanted to be free to travel

and chart her own destiny."

According to Kate Devlin, a writer

forTrowelblazers.com, Harvard anthropologist Alfred Tozzer once said,

“You look at Miss Breton and set her down as a weak, frail and delicate

person who goes into convulsions at the sight of the slightest

unconventionality in the way of living. But I assure you, her

appearance is utterly at variance with her real self.”

Adela

Breton died at age 73 in Barbados in 1923 and left most of her work and

collection to the Bristol Museum & Art Gallery, the best of

which

is now on display (until May 14, 2017) in an exhibition entitled Adela Breton: Ancient Mexico in Colour. “It will be

the first time the life-size copies have been displayed for 70 years,”

says Senior Curator Sue Giles, “and they probably won’t be displayed

again for another 70.”

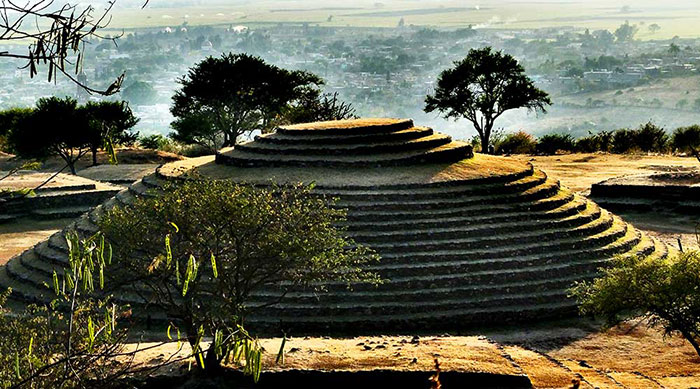

Guachimontón Number Two "La Iguana" today -- Photo by

John Pint

|