The Amparo Mining Company:

Bonanza to Bust

By John Pint

Several of Mexico's richest gold and silver mines were located near the

town of Etzatlán, Jalisco, which lies 70 kilometers west of

Guadalajara. They were operated by an American concern, the Amparo

Mining Company. Over the years I've collected stories about the

extraordinary prosperity which the mines brought not only to the

foreign managers, but to the miners as well, all of whom appeared to

have formed one big, happy family.

The only fly in the ointment was the fact that most of those miners

went on strike in 1926, which eventually resulted in the closing of all

the mines in the hills above Etzatlán. The miners had high salaries,

free housing, free education, two supermarkets offering the finest food

and clothing in the whole country, a first-class hospital, baseball,

several orchestras, soccer, basketball, volleyball, electricity (before

any town in the area) and even their own theater where they could watch

silent movies, talkies, operas and concerts by the greatest artists of

the day.

So why did they march off in protest to Mexico City behind leftist

organizer (and famous muralist) David Alfaro Siqueiros?

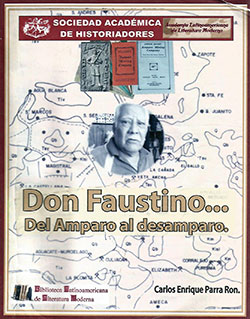

Well, at long last I found some answers to my questions in a newly

published book by the historiador of Etzatlán, Carlos Enrique Parra

Ron. The title is “Don Faustino... del Amparo al Desamparo,” which

might roughly be translated as “Don Faustino... Amparo from Bonanza to

Bust.”

Don Faustino Hernández was, says Parra, a man over 80 years old who one

day walked into his office and proudly announced “that he had been born

and bred in the legendary mining town of Amparo and that he was willing

to collaborate with me in the intriguing task of rescuing fragments of

the extraordinary history of that enigmatic enterprise.”

In the book, Don Faustino describes what went on inside the mines in

his day. The drillers, he said, would go down to the very end of the

tunnels with their helpers. Here they bored holes which they filled

with dynamite. Then, when the fuses were lit, they would shout, “¡Ya

está pegado!” which meant “Run for your lives!”

After

the explosions, the “tenateros” would go in with big, bag-like,

containers made of crude leather with a long strap that went around the

tenatero's forehead. They would fill the bags with rocks and lug them

up notched-tree-trunk “ladders” until they reached the outside.

At Las Jiménez, the ore was ground into powder and transformed into

silver and gold ingots, except for a few grams which were minted into

coins to pay the miners. The ingots were then trucked (with eight men

guarding them) to the Etzatlán train station, from which they went off

to Guadalajara and other points in Mexico and the USA.

“In the early days,” declared Don Faustino, “these mines were dangerous

and caused numerous deaths. The tenateros were constantly running risks

with never a chance to rest. They were treated as subhumans, breathing

God-knows what kind of air, under the threat of collapses in which they

would either be trapped or torn to pieces.”

Don Faustino adds that the “patrones” would hire children even below

the age of 12 to be tenateros, obliged to carry their leather

containers of rocks through the dark, humid, hot mine shafts,

occasionally dragging them through narrow crawlways.

“Many of these workers,” continued Don Faustino, “only lasted five or

six years in the mine and ended up as what we called 'cascados' or

'broken men': pallid, coughing and unable to work. We thought they had

contracted pneumonia from the drastic change of temperature between the

hot, humid mine shafts and the cool outside air. They were considered

retired, but would still receive their salaries. We would see them

sitting around, totally exhausted and coughing and coughing.”

Today, it's known that what those miners had been suffering from was

acute silicosis, which develops after exposure to high concentrations

of breathable silica dust, which is a bit like ground glass. This

results in severe shortness of breath, cough, fatigue, fever, chest

pain, “blue skin,” and weight loss, often leading to death. Victims of

acute silicosis are particularly susceptible to tuberculosis infection,

possibly because the silica damages the white blood cells which would

normally kill the bacteria that cause TB.

“So,” says Don Faustino, “those miners who had once been well loved

were now shunned, because people thought what they had was contagious.

Little by little they would fade away, leaving their families in dire

straits because the compensation their survivors got from the company

was pitiful.”

Apart from the interviews with Don Faustino, Carlos Parra's new book

contains eight pages on the unionization of the miners and the end of

mining operations at and around Amparo. This information was provided

by another informant, closely involved in the final stages of Amparo's

history, Don Emilio Balbuena.

It seems that in 1926 two competing unions had been formed at Amparo,

one called Los Rojos (The Reds), organized by David Alfaro Siqueiros,

and the other Los Polveados (Those Covered with Dust). Somehow, the

leader of Mexico's National Union of Miners, Filiberto Ruvalcaba,

managed to get the two to work together and ask the management for a

salary increase. This the company flatly refused, stating that the mine

was no longer producing high yields.

So, the miners went on strike and stayed on strike for five months, but

the company refused to bend. Then Ruvalcaba suggested they take their

disagreement with the “Gringos” to Mexico City, directly to Los Pinos,

and the miners agreed. At three in the morning, 400 of them set off on

foot from Las Jiménez, reaching Teuchitlán at 10 AM.

“We sat down under shady Guamuchil trees,” says Balbuena, “and heated

up our tacos. Then we kept walking to Tala where we stopped to sleep.

Up again at 3:00 AM, we continued on our way to La Primavera where we

took a rest. But when we started walking again, the older miners and

the cascados began to lag behind.”

The first of the strikers to reach Guadalajara sent 20 taxis back to

pick up the old and the infirm and then, rallying at La Minerva

Glorieta (roundabout), the miners marched down Avenida Vallarta four

abreast “in an endless line” to the Social Security Clinic at Agua

Azul, which became their temporary home. Here other unionized workers

brought them a cow to eat and a giant copper cazo to cook it in and the

governor pledged to come to their assistance.

Says Balbuena: “Our leaders then went to an arbitration facility in the

D.F. where they passed several weeks fighting against the

representatives of the mining company. Finally, Señor Ruvalcaba called

us, saying the company had refused to grant our petitions and we should

get our things together because early the next morning we were all

going to march on the capitol. But the next day, just as we were about

to leave, he called again to announce that the mining company had

finally agreed to give us not only compensation, but the mine as well.

The railroad union then arranged to get all of us back to Etzatlán and

the day after our arrival, we held a big meeting to choose a Board of

Directors, because from that moment we were nuestros propios patrones,

our own bosses.”

Don Emilio's account of what subsequently happened to the mine in the

hands of the union is just as full of pathos, exhilaration, greed,

betrayal and tragedy as the first part of its history, but I have no

more room to tell it. Suffice it to say that—thanks to this information

published by historian Carlos Parra—it has been revealed that the Saga

of the Amparo Mines has all the ingredients—and then some—for a

blockbuster movie, with enough of a dark side even to merit the

interest of that master of horror, Guillermo del Toro. Are you paying

attention, Memo?

Don Faustino Hernández died in Guadalajara in 2015, just days short of

his 86th birthday. Carlos Parra's office is in the restored Etzatlán

train station, which also houses the Mining Museum.

Children's orchestra at El Amparo.

If you like this article check out "A Visit to Amparo."

If you like this article check out "A Visit to Amparo."

Text and Photos © 2019 by John & Susy Pint unless

otherwise indicated.

HOME

|