|

By John Pint

On

Wednesday, March 6, 2013, the first book ever on the geology of

Mexico's Primavera

Forest was launched at ITESO University in Guadalajara. “La Apasionante

Geología del Área de Protección de Flora y Fauna La Primavera” was

written by U.S. Peace Corps Volunteer and geologist Barbara Dye during

her two years of service at the woodland sanctuary. Although written in

Spanish, the 72-page book has so many stunning color photos and

drawings that it could also be considered a coffee-table book which

speakers of any language will enjoy perusing.

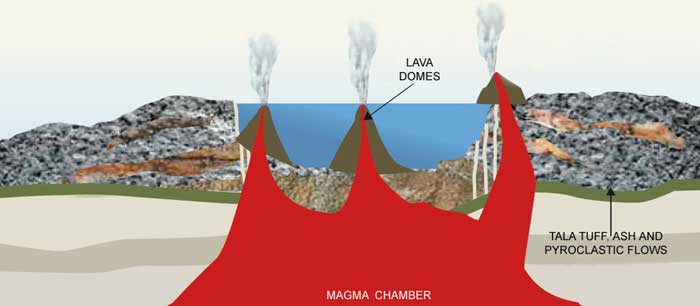

This

cross-section shows the Primavera area after the caldera filled with

water, turning into a lake. Domes then rose up, and their tops hardened

into giant layers of pumice. Illustration by Barbara Dye and Alfredo

Valle

Beltrán.

For most people

who live in Jalisco, Mexico, Barbara Dye’s book will be a real

eye-opener. What we call a forest, she tells us, is also home to a

volcano just as real as Colima’s Fire Volcano or Mexico City’s

Popocatépetl. Underlying the beautiful oak and pine forest, she says,

is a vast chamber of red-hot magma which, 95,000 years ago gave rise to

an explosion so tremendous it is actually listed among the world’s

biggest bangs (near the bottom of the list, I must admit). The amazing

thing is that the same seething lake of molten rock is still right

there underneath the Primavera Forest, the source of its famous Río

Caliente as well as its less-known but spectacular live fumaroles.

Dye

illustrates the dramatic history of the Bosque’s volcanism with a

series of well-drawn, easy to understand sketches. We see how the magma

chamber began to grow 140,000 years ago, producing so much pressure

that it finally exploded 45,000 years later, shooting twenty cubic

kilometers of material straight up into the air. So big was the

explosion that the upper part of the chamber collapsed, creating a huge

hole 11 kilometers wide, in the shape of a giant bowl, known to

geologists as a caldera.

Of course, what went up eventually came

back down, mainly as various forms of rhyolite. This explosion is the

source of the pumice and ash which covers 700 square kilometers of land

around Guadalajara and is locally referred to as “jal.” And, of course,

Jalisco is “The Place Where You Find Jal.”

Dye’s book shows us

how the caldera soon filled with water, creating a big lake. In time,

the magma down below pushed upward again, creating domes which rose

like islands in the lake. Dye’s book shows us

how the caldera soon filled with water, creating a big lake. In time,

the magma down below pushed upward again, creating domes which rose

like islands in the lake.

Minor explosions issued forth from these domes and pumice hardened at their tops. Eventually huge

blocks of pumice spalled off and ended up floating on the lake for

a while, later sinking to form some of the world’s most dramatic

deposits of pumice. You can see evidence of the lake sediments and the

Giant-Pumice Horizon in the canyon walls near Pinar de la Venta and

Mariano Otero.

After 20,000 years, the lake vanished as the center of the Caldera

“lifted like a piston,” draining away all the water.

Since

then, the magma chamber has become active in some way about once every

30,000 years. The most recent event was the eruption of El Colli, the

big hill you can see just behind Guadalajara's Omnilife Stadium, and El

Tajo, the

hill where Bugambillias housing development now stands. Although the

center of vulcanism has probably moved away, note that 30,000

years have passed

since these events took place. Will we see more activity in the near

future? Who knows, but meanwhile we have impressive canyon walls and

Barbara Dye's book to remind us of the Primavera Forest's exciting

geological history.

Besides rocks, Geology

of

the Primavera also talks about the animals which inhabited this area in

the past. In this drawing by Sergio de la Rosa, the Pleistocene

megafauna are conveniently lined up for inspection. Note the giant bear

and camel which once roamed this forest.

This book on the geology of the Primavera arrives just at the moment an

ad-hoc group is pushing for the creation

of a Geopark

in the same forest, a place where local people and visitors from around

the world can learn about the “passionate history” (as Barbara Dye

calls it) of this caldera, while gazing at canyon walls, soaking in hot

rivers and strolling among the bizarrely shaped rock formations

produced here by nearly 100,000 years of volcanic activity. If Jalisco

authorities take a liking to the idea, the Primavera Caldera could

become the first UNESCO Geopark in Mexico, and join an international

network of 90 Geoparks which now attract geotourists from all over the

world.

Unfortunately, copies of this fine book are no longer available. However, you can download it as a PDF. Just check the sidebar. |