Studies show leaf blowers pose unexpected

health hazards, especially for Mexico

Mexican kids: what is in the air

they’re breathing and what is their future? Photo: John Pint

By John Pint

A recent analysis by the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai

Hospital in New York City indicates that the air and noise pollution

from gas leaf blowers (GLBs) seriously impact respiratory health and

are also associated with problems like cancer, heart disease and

dementia—and that children, in particular, are highly susceptible to

these hazards.

A separate study shows how extremely tiny particles of metal from small

gas engines can be carried directly to the brain via the olfactory

nerve, producing the features of autism, attention-deficit disorder,

and schizophrenia.

These studies suppose seasonal use of GLBs to blow leaves off paths,

not the heavy and frequent use now in vogue throughout Mexico.

The

toxic cloud from a leaf blower can remain in the air for hours or even

days.

The Mount Sinai scientists point out that GLB combustion engines are of

extremely low efficiency; 30% of the gas and oil they use is unburned

and released directly to the atmosphere. They cite the estimate of the

California Air Resources board that operation of a GLB for one hour

releases emissions equivalent to driving a car for 15 hours or 1,100

miles.

The GLB emissions include carbon monoxide, formaldehyde, benzene, and

extremely small fragments of metal (less than 50 nanometers) from the

combustion chamber. When these are mixed with particulate matter blown

off the ground, the result is a toxic cloud which can remain suspended

in the air for up to 5 hours.

Fine particles lifted off the ground and into the air may include mold,

pesticides, pollen and heavy metals as well as the excrement of birds,

bats, dogs and cats.

To this must be added a noise level of more than 100 decibels, the

equivalent to a jackhammer or a jet taking off, a level that eventually

leads to irreparable hearing loss. Not only that, points out Mt.

Sinai's Dr. Sarah Evans, chronic noise exposure has been shown to

increase your risk of cardiovascular disease, anxiety and depression,

and impaired focus and cognition.

When the leaf blower appeared on the market in the 1980s, some Mexicans

saw it as an easy way to carry on an old custom of washing the street

outside one’s door early each morning,

That tradition has deep, preHispanic roots. It is said that the city of

Tenochtitlán had a team of a thousand men to sweep and wash its streets

every single day. This preoccupation with the look of the ground

outside your door is still around today, but some people have

replaced brooms, buckets and water with a machine that seems to do the

job quicker, without realizing that this same device throws extremely

tiny particles into the air, particles 30 percent smaller than the

width of a human hair.

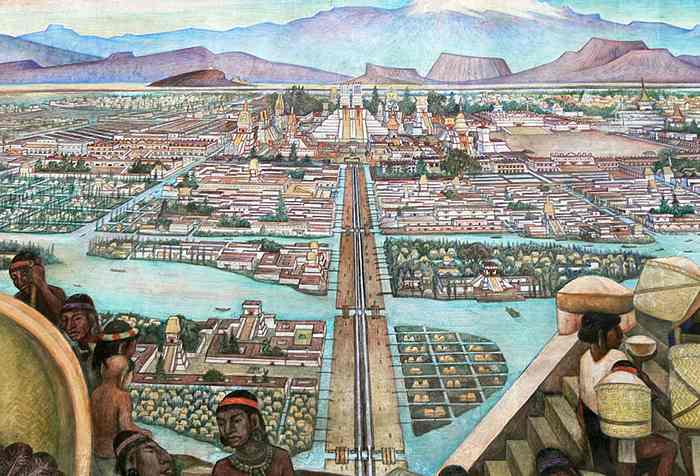

Tenochtitlán

as Diego River imagined it. A thousand workers cleaned the streets

every day

The fine particles remain airborne for long periods of time,

infiltrating buildings. What these microscopic specks do to you, once

they reach your nose is something that has become of great concern to

researchers.

In the second study—included in the Proceedings of the National Academy

of Sciences—neurotoxicologist Deborah Cory-Slechta at the University of

Rochester in New York. states that these tiny particles can go up the

nose and be carried straight to the brain via the olfactory nerve,

bypassing the blood-brain barrier.

Unfortunately, these nanofragments don't travel alone.

On their surfaces the particles carry contaminants, from dioxins and

other chemical compounds, to metals such as iron and lead. “Particulate

matter may be acting as a vector,” says Masashi Kitazawa, a molecular

neurotoxicologist at the University of California, Irvine. “It might be

a number of chemicals that get into the brain and act in different ways

to cause damage. Ultrafine particles are like little Trojan horses.

Pretty much every metal known to humans is on these."

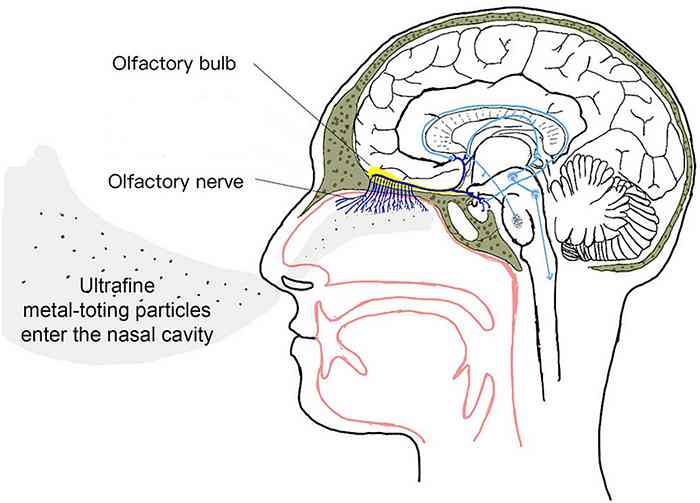

Tiny

particles of metal from leaf blowers enter the brain via the olfactory

nerve. Image after Wang et al.

Metal-toting particles that reach the brain can directly damage

neurons, says Cory-Slechta. “Both the particles themselves and their

toxic hitchhikers can also cause widespread harm by dysregulating the

activation of microglia, the immune cells in the brain. Microglia may

mistake the intruders for pathogens, releasing chemicals to try to kill

them. Those chemicals can accumulate and trigger inflammation. And

chronic inflammation in the brain has been implicated in

neurodegeneration.”

In January 2010, Cory-Slechta received a surprising request from some

University of Rochester environmental medicine colleagues. Typically,

the group researched the effects of air pollution on the lungs and

hearts of adult animals. But they had just exposed a group of newborn

mice and asked Cory-Slechta’s team to look at the brains.

At first she didn’t think much of the request. Cory-Slechta was much

more concerned about deadly lead exposure in children, her research

focus at the time. “I didn’t think of air pollution as a big problem

for the brain,” she says. Then she examined the animals’ tissue. “It

was eye-opening. I couldn’t find a brain region that didn't have some

kind of inflammation.”

Her team followed up with their own studies. In addition to

inflammation, they saw classic behavioral and biochemical features of

autism, attention-deficit disorder, and schizophrenia in mice exposed

to pollutants during the first days after birth.

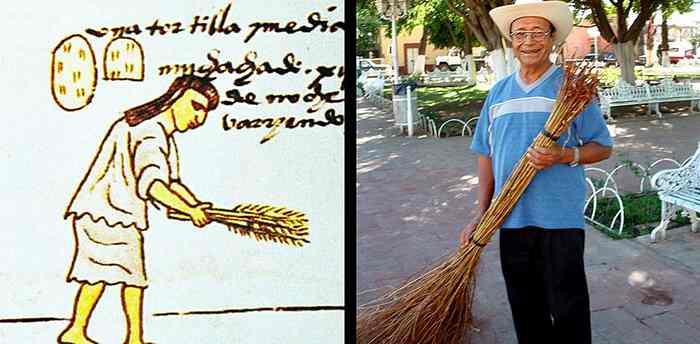

Continuity:

The plaza of Teuchitlán is swept with a kind of broom that has been

used in Mexico for centuries.

Based on MRI scans, cognitive tests, and measures of inflammatory

markers in the blood, the team identified neuroinflammation, brain

structure changes, cognitive deficits, and Alzheimer’s-like pathologies

in apparently healthy children living in Mexico City, compared with a

group of similar children in a less polluted city. The findings,

according to the authors, suggested that dirty air may spur brain

disease at far younger ages than previously suspected.

If you don’t live in Mexico City, you can still experience plenty of

the bad effects of air pollution simply by opening the window wide when

your neighbor turns on his leaf blower.

"No leaf blower for me!"

says Valentina Ramírez of Guadalajara

Text and Photos © 2023 by John & Susy Pint unless

otherwise indicated.

HOME

|