A lonely stretch of desert in Zacatecas.

Cave Vandalism and Cave Protection:

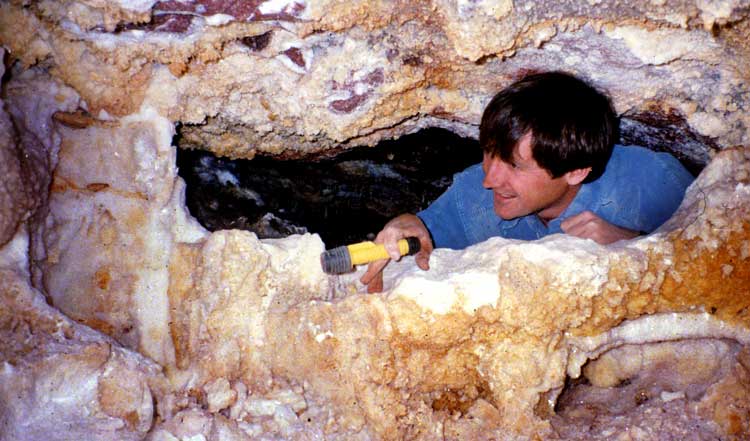

Geologist Nick Hawks inside one of the caves discovered by miners in Zacatecas, Mexico

“MEXICO HAS NO LAW PROTECTING CAVES” are the final words at the end of the film

Naica, Journey to the Crystal Cave, reminding us that Peñoles, the mining

company which owns the cave, could grind up the unique, giant crystals of this

cave and turn them into toothpaste if it wanted to, and it would be perfectly

legal.

We have, therefore, resurrected this true story of our visit fourteen years ago

to several natural caves found in two other mines in Zacatecas, also owned by

Peñoles. We hope what you are about to read will encourage you to help support

the movement to ban cave vandalism in Mexico.

John and Susy Pint

April, 1996. "The caves I saw are absolutely marvelous," exclaimed a

geologist friend of ours. "The ceilings, the floors, every inch of the walls are

covered with crystals ── it's as if you had walked into a gigantic geode."

There were a few hitches, however. First, it seemed the stupendous caves in

question were located deep inside some silver and gold mines which, in turn, are

located far, far, away in northern Mexico. Besides that, we would need

permission to enter the mines and to take photographs. But our friend assured us

he would cut through the red tape. All in all, it sounded like a well worthwhile

project, as these caves ── which had no natural entrances ── were destined to be

destroyed "in the normal course of mining operations" and our photos might

someday be the only records of their existence.

|

When the long Easter holidays arrived, we packed up our little Bug and drove

eight hours north, through the seemingly endless Zacatecan desert, to the

famed mining town of Concepción de Oro, nestled among barren mountains

pockmarked with black gaping holes and enormous mounds of slag, sludge or

whatever miners call the goop left over after the precious minerals are

extracted.

|

|

CHOKING ON DUST

We drove up and down Concepción's steep, narrow streets past quaint little

houses and shops right out of the 1800's, looking for the road to Mazapil, a

small town somewhere out there in the desert, not far away. Finally someone told

us that there simply was no road to Mazapil, even though our map showed one.

However, back on the main highway we were guided to an unpaved road buried under

three inches of fine white powder. We were told that if we really stepped on the

gas, we might reach Mazapil before sunset. Unfortunately, we didn't get far

before we came to a fork in the road, naturally with no signs whatsoever. But as

luck would have it, a truck came along just then and just happened to be going

to Mazapil. So we asked if we could tail them and in no time learned all about

the advantages and disadvantages of following someone through the desert on

those powdery roads. The disadvantages are that you can't breathe and you can't

see. The advantage (just about the only one), however, is that—should the car

you are following race ahead at breakneck speed—you can always spot that choking

white dust cloud, no matter how far you get behind or how many times the road

divides.

The bright green Joshua trees stood like prophets with arms raised in

supplication, between us and the smoothly sculpted mountains in the distance,

and everything was bathed in the golden rays of the setting sun. I only wish it

hadn't been setting precisely in front of us, turning that dust cloud we were

following into a blinding white swirl that left us with zero visibility.

Squinting and choking, we drove into town just as darkness descended. We stopped

to ask some kids for the home of our friend's friend, Pancho. "He's our papá,"

they replied, "but he's not at home now; he's at the cantina."

CUTTING RED TAPE

There's only one thing you'd be doing at a cantina on a holiday, so we weren't

surprised when Pancho staggered out the door with a bottle of tequila in his

hand and a big grin on his face. Soon we learned, however, that the grin was due

to genuine happiness at seeing us and not merely to the contents of his bottle.

Any friends of his friend were Pancho's friends too and he'd be delighted to

take us to the mine the next morning, hangover or not. But in no way would he

allow us to go off to camp in the desert. We were to sleep in the mining

company's facilities; all we'd need was the key, which Pancho would get from

Señora Fulana who was attending Mass just now. So we chatted about mines, caves,

geology and whatnot until Señora Fulana appeared.

"The key?" Oh, I can't give it to you without written permission."

Fortunately, even remote places like Mazapil have telephones and soon we had the

Guadalajara boss of the mining company on the line. Unfortunately, however, our

friend who had promised to "cut the red tape" had only informed the American

boss in Tucson about our visit and not the Mexican jefe.

"NO!" came the final word from Guadalajara, "you CAN'T stay in our facility and

you can't visit the mines either. And by the way, your friend no longer works

for us. So there!"

This was not turning out quite the way we had figured. Twelve hours on the road

and the whole project squelched because of somebody's petty squabbling.

We left town and slept beneath a moon so bright you could read the fine print on

an insurance policy... in case you'd ever want to do that instead of enjoying

the sounds and sights of the desert at night. The next morning we went hunting

for Nick Hawkes, a geologist friend who had planned to meet up with us in

Mazapil.

Nick was all smiles. "I've just talked with Pancho and he's decided to take us

to the mines anyhow." It turned out that some of the mines with caves in them

hadn't yet been purchased by the uncooperative mining company. So, according to

Pancho, they had no right to forbid us entry. Besides, the guard responsible for

keeping us out was none other than Pancho's cousin, whom we had met at the

cantina last night. There is something they call the "Mexican Standoff" but here

was what you might call the "Mexican Solution." It was an excellent example of

how the impossible can become possible in Mexico.

INTO THE MINE

|

The "road" up to the mines was another dusty delight, especially for those of us riding in the open bed of Nick's truck. There was the usual lack of shoulders and the usual 1000 foot drop on one side, but this road was so narrow you almost had to fold the truck to get it around the hairpin curves. The last curve, in fact, was so tight, we just abandoned the vehicle there and walked the rest of the way up. Hiking to the mine entrance |

|

|

In the ceiling of this cave, Pancho pointed to a hole just big enough for

one person. "Up there is a small room where none of the crystals have been

damaged," he said. Nick and I climbed up into what our eyes could have taken

to be a cave completely carved in pure, glistening snow...

|

|

It was oh so beautiful, but we didn't bring up the video camera and we didn't

take a single picture. We were just too jolted by the contrast we were

experiencing. Nature had made this little room so perfect and there it was, up

and out of the way, bothering no one... yet someone had decided to use it as a

toilet.

YECH!

The browns and blacks of several deposits of human excrement on the sparkling

white "snow" seemed like some sort of allegory on nature's purity besmirched and

I felt a bit like Dr. Pepe Sanchez who refused to get out of the car to see the

marvelous dance of Michoacan's monarch butterflies, after discovering that their

ancient forest home had been turned into a four-ring circus of soft-drink

stands, ramshackle restaurants, roaring engines and crowds of loud tourists.

I climbed down from that stinking room rather shaken. We exited the mine, went

into another one and this time were taken to an entirely different kind of cave,

again one which had no natural entrance. Here, instead of smooth walls, were a

tangle of stalactites, stalagmites and columns, colored every possible shade of

brown and red. Here, too, were the small pointy gypsum crystals we'd seen in the

other cave.

In the first room we came to, all the soda straws and other breakable formations had been snapped off, but we found several crawlways that were very difficult to negotiate as their floors were covered with crystals as sharp as broken glass. This factor had protected the rooms beyond from damage and we found areas thick with lovely formations.

| ...In the first

room we came to, all the soda straws and other breakable formations had been

snapped off, but we found several crawlways that were very difficult to

negotiate as their floors were covered with crystals as sharp as broken

glass. This factor had protected the rooms beyond from damage and we found

areas thick with lovely formations...

|

|