|

by Peter Ruplinger, Josh Kaggie and Kent Forman

This was our ninth fantastic cave mapping expedition to the

Coahuayana area of Mexico. The Coahuayana valley is on the

border between Colima and Michoacan near the coast.

Now that we’re back, the questions that Kent, Josh, and I are

most often asked are, “Did you find any cool caves?” and “Did

you have any scary experience with drug violence?”

Yes, we explored and mapped nine super caves. We did a lot of

rigorous hiking up steep mountains through dense and beautiful

jungles. We also met a lot of friendly people who were anxious

to help.

No, we didn’t have any scary experiences with drug violence, but

were continually careful where we went and what we did. We

passed two clearly visible marijuana fields and no doubt others,

sheltered from view by dense vegetation. Once we were stopped by

the army, interrogated and searched.

If you are planning a trip to Mexico there are two major points

to remember.

●

Don’t

be out at night.

●

Personally know the people in your immediate area. It is their

“territory”.

The importance of territory can’t be over emphasized. Mexicans

are anxious to help if they know who you are, but if you’re in

the wrong area, and they don’t know you, you may get shot. Don’t

go on other’s property without asking permission. Don’t go into

the back country without a local escort who personally knows the

people where you will be caving.

Similar advice could be offered for Mexican cavers coming to the

United States. Don’t wander or drive into what may be hostile

neighborhoods of major cities, during the day or night.

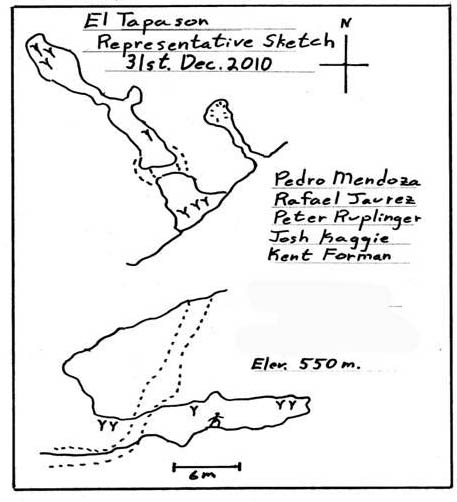

One of our objectives on this trip was to map El Tapazón, a cave

high on the opposite side of the mountain where we have spent

the past few years mapping the river cave, Cueva de Las Canoas.

Pedro, who has helped us on prior trips, introduced us to his

neighbor Rafael who knows the Tapazón side of the mountain well.

We ascended thirteen hundred feet over a distance of two and a

half miles through dense jungle to reach El Tapazón. The name

means “the large covering”. The cave’s entrance has a large

overhang which has sheltered locals for millennia.

The cave was somewhat of a disappointment. We heard that it was

large and possibly connected to Cueva de Las Canoas. The cave

only went in about seventy feet. It was, however a beautiful

cave with numerous formations.

Pedro ventured in the cave with us. Rafael had

promised his mother that he wouldn’t go into it. So, he stayed

outside and prepared us a scrumptious barbeque with venison from

a deer that he had shot just the day before.

His

mother believes caves are inhabited by evil spirits. Perhaps she

is correct. We didn’t see any ghosts, but we did see several

large spider like creatures which the locals call “Tindarapos.”

Cavers know them as “Amblypigids”. They have pinchers and leg

spans sometimes exceeding 22 inches”! They are totally blind.

They don’t worry me at all. What do bother me are the tarantula

size, black spiders which we often see in Coahuayana caves. Like

Tindarapos, they are totally blind. Unlike tarantulas, they have

pointed legs and delicate little fangs. They give me the

creeps!. His

mother believes caves are inhabited by evil spirits. Perhaps she

is correct. We didn’t see any ghosts, but we did see several

large spider like creatures which the locals call “Tindarapos.”

Cavers know them as “Amblypigids”. They have pinchers and leg

spans sometimes exceeding 22 inches”! They are totally blind.

They don’t worry me at all. What do bother me are the tarantula

size, black spiders which we often see in Coahuayana caves. Like

Tindarapos, they are totally blind. Unlike tarantulas, they have

pointed legs and delicate little fangs. They give me the

creeps!.

Almost adjacent to El

Tapazón

was a small fissure cave that went in about thirty feet and then

up as a chimney approximately forty feet to the surface.

A stone’s throw to the south was a small tomb-like cave about

four feet in diameter. It went down about ten feet, over ten

feet, and down another twenty feet. Due to its structure, we

named it, “Pierna del Perro”, (Dog Leg).

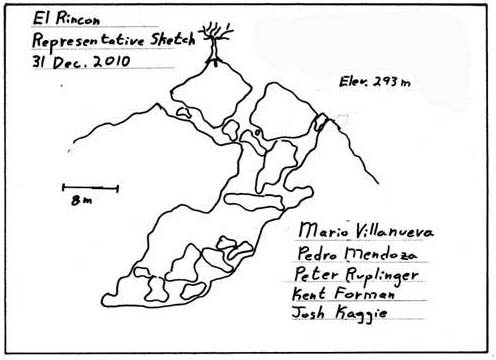

On

our descent, we teamed up with Mario, another of Pedro’s

friends. He took us to a hill topped with a mound of sharp

jagged limestone. Snake-like roots wove over the mound like

countless guardian serpents. Under the mound was a maze of cave

passages. In the lower area there were numerous shards. Some say

that indigenous peoples would take pots into caves and then, as

part of a ceremony, break them. The cave wasn’t immense, but its

Swiss-cheese-like passages didn’t permit time for mapping. It

has entrances on the east and west sides of the mound. Locals

know this cave as, “El Rincón” (The Corner}. I don’t know why. On

our descent, we teamed up with Mario, another of Pedro’s

friends. He took us to a hill topped with a mound of sharp

jagged limestone. Snake-like roots wove over the mound like

countless guardian serpents. Under the mound was a maze of cave

passages. In the lower area there were numerous shards. Some say

that indigenous peoples would take pots into caves and then, as

part of a ceremony, break them. The cave wasn’t immense, but its

Swiss-cheese-like passages didn’t permit time for mapping. It

has entrances on the east and west sides of the mound. Locals

know this cave as, “El Rincón” (The Corner}. I don’t know why.

To the east of El Rincón was a small cave which may have been

used as a tomb. Mario chose to name it “Cueva del Javero.”

Javero is the name of a large tree below the cave.

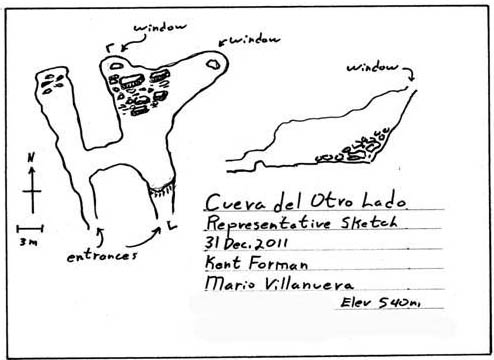

While I was preparing a representative sketch of El Rincón, Kent

and Josh went to the west side of El Rincón and explored our

sixth cave for the day. Mario scratched his head and couldn’t

think of a name for it, so I named it, “Cueva del Otro Lado”

(Cave on the other side).

It was a rough day. In the evening a local family Ricardo and

Maria invited us for dinner. It was a lot of fun. Their two

charming teenaged daughters were enchanted with Josh and dragged

him off to a karaoke party to usher in the new year. Josh came

back a little after twelve boasting that he had sung Moon River.

In the meantime, Kent became a hero by fixing the families’

virus infected computer. I shocked everyone by relating a story

about finding a venomous snake in the cave, and then producing

it from within my shirt. It was rubber of course. Exon, their

eight year old boy roared with laughter and was delighted when I

gave him the snake.

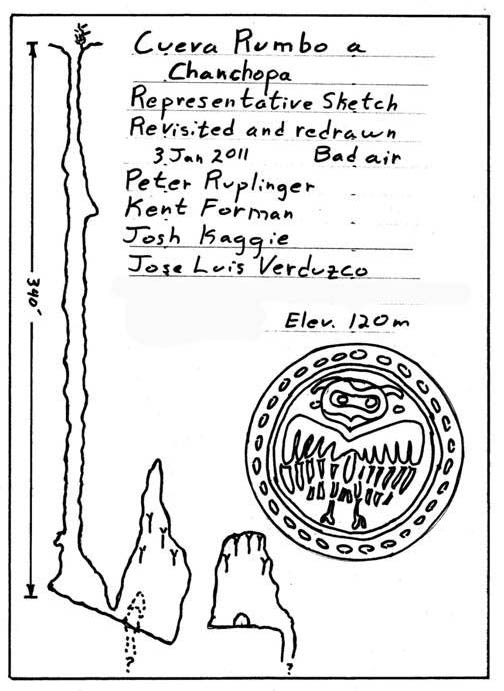

The next day we made a return trip to “Cueva del Rumbo a

Chanchopa” (Cave on the way to Chanchopa). It is located north

of the Coahuayana valley, near the town of San Gabriel,

“Chanchopa” is the name of the town at the base of the mountain

where San Gabriel is nested. “Chancho” is one of several Mexican

words for “pig”. There is a large hog farm in Chanchopa, so

perhaps the town is named after the hog farm. The people there

go out of their way to be cordial, but the area stinks. How

would you like to live in a stinky town called “Pigville”?

During last year’s visit to San Gabriel, Rodney Mulder descended

the pit, but due to the late hour, Kent and I didn’t have time.

On this trip we did. The cave is over four hundred feet deep. It

took nine minutes to descend and twenty-five to climb out. Kent

and I both came face to face, just inches away, with one of

those big black ugly spiders.

At the bottom the air was bad. A cigarette lighter wouldn’t

begin to light. Kent and I had to breathe twice as fast. I

didn’t venture past the room where we got off rope. Kent went on

to a second, highly decorated room with a hundred foot ceiling.

This second room had a pit at the far end. Due to the bad air,

Kent prudently didn’t drop the cave’s second pit.

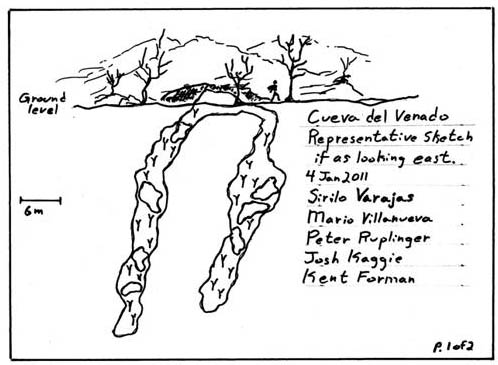

Two days later, back in Palos Marias, one of the town’s oldest

residents, Sirilo, took us to a cave near the summit of the

immense mountain north east of Palos Marias. Sirilo is

eighty-five years old. He has hunted deer and harvested exotic

hardwoods in this area all his life.

Sirilo

rode his little donkey. The rest of us walked. To save time we

didn’t take the switchbacks, but marched straight up the hill.

It was an arduous hike. Josh fell on sharp, weather eroded

limestone and cut his shin. Kent, who always carries every

possibly needed item in his huge backpack, produced butterfly

sutures, and other first-aid items to dress the wound. Sirilo

rode his little donkey. The rest of us walked. To save time we

didn’t take the switchbacks, but marched straight up the hill.

It was an arduous hike. Josh fell on sharp, weather eroded

limestone and cut his shin. Kent, who always carries every

possibly needed item in his huge backpack, produced butterfly

sutures, and other first-aid items to dress the wound.

The scariest experience of our expedition was when an area where

we sat to rest suddenly began to slide down the hill. The rocks

rumbled like thunder. Fortunately they only slid about five

feet. When the rocks stopped, my left leg was pinned to the knee

between two boulders. Fortunately I was able to remove it. We

carefully crept to safer ground.

Sirilo says there are numerous caves on the mountain. It’s just

a matter of finding them. He found this cave ages ago when he

shot a deer. He tracked the wounded deer to the entrance of the

cave, where it had fallen. Sirilo wasn’t aware of a name for the

cave. Mario said we should call it “Cueva del Venado” (Cave of

the Deer).

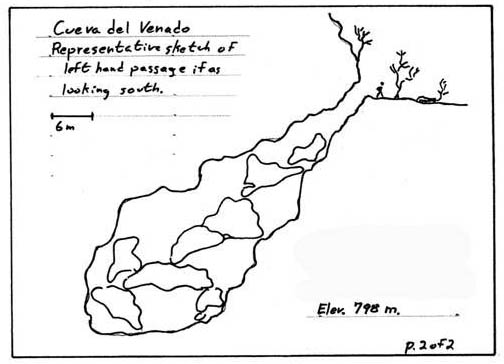

The

cave was in a beautiful area with huge trees. There was only one

opening, but it quickly divided into two parallel fault-like

passages. Once again, we simply did not have time to make a

detailed map. About half way down the right-hand passage, I

found what appeared to be a pedestal. It consisted of four fist

sized stones with a dish-like stone on top of them. It was in a

shrine-like corner area. It was obvious it had been placed there

by hand. Below the pedestal was a large elegant pot, broken to

pieces. The

cave was in a beautiful area with huge trees. There was only one

opening, but it quickly divided into two parallel fault-like

passages. Once again, we simply did not have time to make a

detailed map. About half way down the right-hand passage, I

found what appeared to be a pedestal. It consisted of four fist

sized stones with a dish-like stone on top of them. It was in a

shrine-like corner area. It was obvious it had been placed there

by hand. Below the pedestal was a large elegant pot, broken to

pieces.

Although moderate in size, the cave was heavily decorated.

Almost every surface was covered with veils, stalactites,

stalagmites, and shark tooth draperies.

Our last cave of the expedition was once again on

top of a humongous mountain. I thought our guide, Ramon, looked

familiar. On the hike, once again straight up the hill, he told

us that cavers had been there before, but had not reached the

cave’s bottom due to its immense depth. Once at the cave, I

realized that this was the same cave I had been to in January of

2000. Ten years ago we ascended on the opposite side via

switchbacks. Mario’s younger cousin, Noe, carried our ropes on

his mule. Mario didn’t recognize me now because of my mustache.

The

cave has a spectacular entrance. It is near the top of the

mountain, beside a jagged weathered limestone cliff. The entry

room is about thirty feet across. On the side is a pit about two

by four feet wide. Its lip is covered with slimy black guano.

The pit has an overpowering stench of ammonia. When large rocks

are dropped into the pit, disturbed bats swarm with the sound of

surf smashing on a rocky shore. We could never hear the rocks

hit the bottom. The

cave has a spectacular entrance. It is near the top of the

mountain, beside a jagged weathered limestone cliff. The entry

room is about thirty feet across. On the side is a pit about two

by four feet wide. Its lip is covered with slimy black guano.

The pit has an overpowering stench of ammonia. When large rocks

are dropped into the pit, disturbed bats swarm with the sound of

surf smashing on a rocky shore. We could never hear the rocks

hit the bottom.

This is the cave where Lynn Anderson and I contracted

histoplasmosis ten years earlier. Perhaps that was our

recompense for not descending the abyss. We didn’t descend it

this trip either. Perhaps it is the world’s deepest cave. Who

knows?

THE END

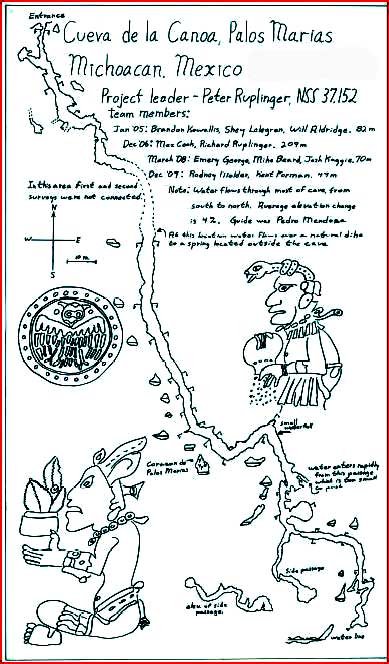

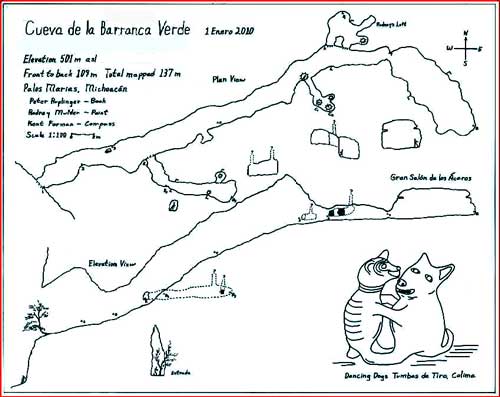

Editor's note: On previous visits to the Palos Marias area,

Peter Ruplinger's team found the two caves whose maps appear

below. Note: the drawings are for decorative purposes only.

There are no artifacts in these caves!

Click on the image to see a larger version of the map. |