|

By John Pint

Jaime Villa is a farmer

who decided two years to start a wildlife sanctuary in the foothills of

Tequila Volcano. Jaime Villa is a farmer

who decided two years to start a wildlife sanctuary in the foothills of

Tequila Volcano.

“The land,” he

explained, “belongs to our ejido and it’s too rocky for

farming. However, it’s extraordinarily beautiful and home to all kinds

of animals and birds. So we applied to the government to set up a

Management Unit for Wildlife Conservation (Unidad de Manejo para la

Conservacion de Vida Silvestre,UMA) on 433 hectares of the land and our

petition was granted.

During the last two

years, with the help of a grant, we’ve created a

nature trail 350 meters long, a site for camping and picnicking, a

hanging bridge, and a mirador with a spectacular view.”

One

thing the members of Ejido Emiliano Zapata (Ahualulco) have not yet

created is a decent road by which an ordinary car could reach the

place, but lucky for us our friend Rodrigo Orozco has a Jeep and one

Sunday we all got together with Jaime Villa to visit UMA Agua Blanca.

We

drove toward Etzatlán on highway 70 and, 7.3 kilometers past

Teuchitlán, turned off the paved highway onto a good dirt road heading

north, following Jaime in his All-Terrain Vehicle.

After 3.5

kilometers, the “goodness” of the dirt road evaporated and we

encountered more and more rocks. Suddenly Jaime stopped. “The Welcome

Center of our UMA is just ahead, but I wonder if you would like to take

a peek at our local pyramid first. It’s at a place called El Saucillo,

just 500 meters from here.” This was said so casually that we assumed

there couldn’t be much to see.

Well, the truth is, /every one of

us except Jaime gasped in astonishment when the ruins came into view.

The pyramid, platforms and ball court were not just easy to recognize,

they were amazingly well preserved and simply beautiful to

behold.

Now

I know from personal experience that before archaeologists came on the

scene, the famed Guachimontones of Teuchitlán were totally hidden

beneath heavy brush and surrounded by cornfields. Even less

visitor-friendly are the mounds of Santa Rosalia which can only be

reached after a long, hard hike up steep hills. In contrast, the

archaeological marvels of this ejido are brush-free, undamaged and only

a two-minute walk from where you park your car.

Before us stood

a large mound 35 meters in diameter encircled by the classical

ring-like walkway of the Teuchitlán Tradition which in turn was

surrounded by clearly defined, regularly spaced platforms. Well, here

there had obviously been eight platforms, but three of them had been

joined together to create what looks exactly like a “bleacher section”

measuring about 80 meters in length. “It looks like this is where the

crowd used to sit while watching the voladores flying through the air,”

we told our host. It took little imagination to see that this ancient

amphitheater could be reconditioned for modern use. “I can see a crowd

of fans watching the Rolling Stones perform up there on top,” I told

Jaime, “but you’ll have to get cracking while the Stones can still

walk.”

Directly north of the Great Mound, there’s an easily

recognizable ball court 70 meters long, in the classical form of a

capital I. Unfortunately, it is cut in half by a modern-day

stone

wall. Due south of the pyramid there’s a set of four small mounds with

a flat patio in the middle. The ball court, pyramid and patio are lined

up perfectly along a north-south line and are surrounded by what appear

to be the ancient ruins of rectangular stone buildings, and wherever

you look you can find ceramic shards and bits of worked obsidian.

I

later found a detailed sketch of El Saucillo Complex made by Phil

Weigand in 1996. I’m sure his heart beat even faster than ours the

first time he walked up to these beautifully preserved ruins.

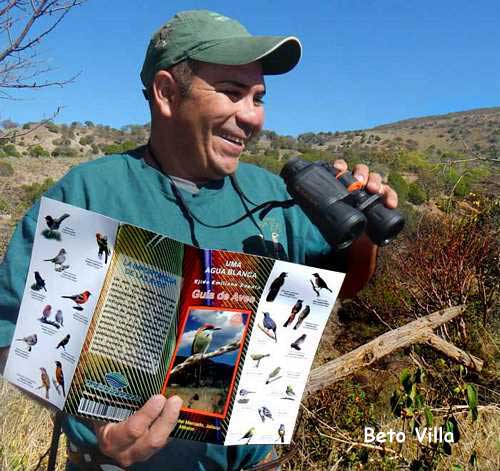

From

the ruins we went to the visitor’s center of Agua Blanca Wildlife

Sanctuary where each of us paid a fee of 20 pesos and received a

beautifully printed triptych showing 55 species of birds which are

frequently seen on the premises, identified in Latin, Spanish and

English.

Next

we began walking along a well constructed trail, with rustic guard

rails, overlooking a deep canyon. This leads to a magnificent hanging

bridge which, when you’re halfway across, makes your legs fell like

they’ve turned to jelly: a real treat for kids, although Grandma may

not appreciate it.

Well shaded by huge black and red cedar trees

as well as oaks, papelillos and strangler figs, the trail leads you

past the spring of milky water which gives this place its name: agua

blanca. “The color comes from minerals,” explained José Zuńiga, one of

the three guides who spontaneously offered to accompany us on our walk.

“It has a distinct taste which you may or may not like, but is quite

safe to drink.”

The trail parallels a rainy-season-only stream

up to a lookout point with a magnificent view of the valleys and

mountains stretching from La Vega Dam to Etzatlán. “From here you can

spot all kinds of birds just after sunrise,” said Jaime Villa’s son

Beto, “such as the Vermilion Flycatcher (Pyrocephalus rubinus), the

Orange-fronted Parakeet (Aratinga canicularis) and the official mascot

of our sanctuary, the Russet-Crowned Motmot (Momotus mexicanus).”

Of

course, to

see this spectacle, you’ll have to camp overnight. For this, there’s a

nice, flat, shady area with toilets and a roofed outdoor dining area.

Added benefits of camping here are the hooting of owls and the howling

of coyotes as the full moon rises over Tequila Volcano, which looms

right above the sanctuary. So if you have a high vehicle and want to

visit this most remarkable wildlife-sanctuary-cum-pyramid, just call

Jaime Villa—who speaks some English—at cell 386 105 2715. He can meet

you at the turnoff (N20 41.384 W103 55.065) from Highway 70 and lead

you up to Agua Blanca.

Telephoning in advance is essential, as the UMA is open by appointment

only.

Rustic dining area at

UMA Agua Blanca with Tequila Volcano looming in the background.

|