|

By John Pint

A

2006 movie called The Peaceful Warrior recounts the story of a

gymnast who suffers a devastating motorcycle accident after

which he is told by doctors that he would be lucky ever to walk

again and cannot possibly continue his career. The gymnast,

however, surprises the doctors, his coach and the entire world

by doggedly retraining himself and eventually going on to the

Olympics, thanks to a kind of mental training and discipline

which he receives from a mysterious figure he names Socrates,

played in this film by Nick Nolte. A

2006 movie called The Peaceful Warrior recounts the story of a

gymnast who suffers a devastating motorcycle accident after

which he is told by doctors that he would be lucky ever to walk

again and cannot possibly continue his career. The gymnast,

however, surprises the doctors, his coach and the entire world

by doggedly retraining himself and eventually going on to the

Olympics, thanks to a kind of mental training and discipline

which he receives from a mysterious figure he names Socrates,

played in this film by Nick Nolte.

Amazingly, the substance of this story is true and is based on

the life of Trampoline athlete Dave Millman who suffered a

crushed femur in 1968 and—against all odds—came back to become a

champion in his field. Socrates, instead, is a fictional

character who seems to be loosely based on Carlos Castaneda’s

Don Juan. In fact, the philosophy of The Peaceful Warrior very

much resembles the outlook and training of a warrior which

Castaneda describes in 12 volumes published between 1968 and

1999.

The first few books written by Castaneda focused on psychotropic

plants and related rituals, as explained and demonstrated by Don

Juan Matus, a Yaqui Indian he met in a bus station in 1960. Only

years later did Castaneda realize that his mentor was also

training him in “the warrior’s way,” a philosophy and discipline

which has been passed down from shaman to shaman in Mexico for

centuries. Finally, when Castaneda himself was well on the road

to becoming a brujo (sorcerer, seer. shaman, man of

knowledge), Don Juan admitted the truth, that peyote rituals

were of no interest to him at all: “I tricked you by holding

your attention on items of your world which held a profound

fascination for you and you swallowed it, hook, line and

sinker.”

Eventually, Castaneda extracted the really important lessons of

Don Juan from his earlier notes and published them in The

Wheel of Time: The Shamans of Ancient Mexico, Their Thoughts

About Life, Death and the Universe (Washington Square Press,

New York, 1998). What kind of ideas have been collected in this

book? Here are a few excerpts:

“The

thrust of the warrior’s way is to dethrone self-importance. And

everything the warriors do is directed toward accomplishing this

goal.”

“Self-importance is man’s greatest enemy. What weakens him is

feeling offended by the deeds and misdeeds of his fellow men.

Self-importance requires that one spend most of one’s life

offended by something or someone.”

“The basic difference between an ordinary man and a warrior is

that a warrior takes everything as a challenge, while an

ordinary man takes everything as a blessing or as a curse.”

“People’s actions no longer affect a warrior when he has no more

expectations of any kind. A strange peace becomes the ruling

force in his life. He has adopted one of the concepts of a

warrior’s life—detachment.”

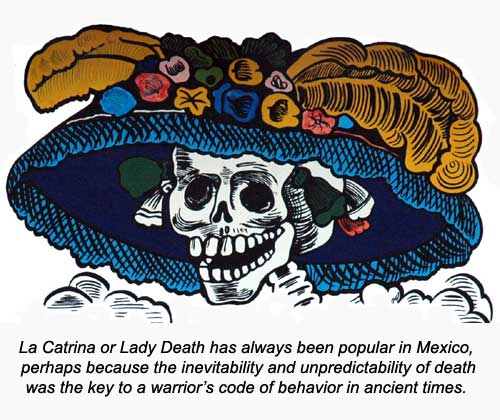

The

theme of death, so prominent in Mexico’s traditions, plays a key

role in the warrior’s outlook:

“The

worst that could happen to us is that we have to die, and since

that is already our unalterable fate, we are free; those who

have lost everything no longer have anything to fear.”

“Death is our eternal companion. It is always to our left, an

arm’s length behind us. Death is the only wise adviser that a

warrior has. Whenever he feels that everything is going wrong

and he’s about to be annihilated, he can turn to his death and

ask if that is so. His death will tell him that he is wrong,

that nothing really matters outside its touch. His death will

tell him, ‘I haven’t touched you yet.’”

In

1976, Castaneda’s veracity was attacked by Scientology

propagandist and freelance writer Richard de Mille, (nephew of

Cecil B.) who established a timeline for several of the early

books, pointed out numerous discrepancies and concluded that

Castaneda’s writings were fiction.

As a lifetime writer of non-fiction, I found de Mille’s

arguments most interesting. I often write about places like

hard-to-reach caves, crater lakes, bubbling mud pots and such,

which most people have never visited. Before putting anything on

paper, I may go to sites like these several times and perhaps

even camp there. When I finally sit down to write an article on

one of these sites, I inevitably merge numerous visits into one

and frequently “quote” my friends, informants and the local

people we met, using words that I think capture the essence of

what they said, but which don’t exactly display the accuracy of

the Nixon Tapes, for example. By De Mille's criteria, most

of my articles are now fiction!

I have also written a number of technical reports over the years

and I can assure you that these make far less interesting

reading than the narrative form, that very same style of writing

employed by explorers and observers like Richard Francis Burton,

Henry Morton Stanley, Bernal Diaz del Castillo, Thor Heyerdahl

and T.E. Lawrence. I’m afraid that neither my writings nor the

writings of these celebrated authors could ever survive the

nit-picking criticism of a de Mille, especially The Seven

Pillars of Wisdom, which Lawrence was obliged to rewrite from

memory after his original manuscript was lost.

Shall we then conclude that A Personal Narrative of a

Pilgrimage to Al-Medinah and Meccah, How I found Livingstone,

and Kon-Tiki are fiction? I note that Castaneda’s

professor at UCLA, highly respected archeologist and

anthropologist Clement Meighan, said the following about

Castaneda in 1989 (thirteen years after de Mille’s attacks): “I

had absolutely no reason to think and I still don’t think that

he was faking it… I know this stuff is authentic. I know he got

it from an Indian.” Perhaps de Mille has committed the classic

sin of throwing the baby out with the bath water.

As the years pass, other writers—such as Miguel Angel Ruiz, who

was raised in Mexico by brujos, have appeared on the

scene to describe the philosophy of Mexican shamans in terms

that mirror the thought-provoking quotations in Carlos

Castaneda’s Wheel of Time, lending support to the contention

that these words do indeed offer us an insight into a

well-thought-out philosophy that some day may be considered

Mexico’s most important contribution to mankind’s understanding

of itself and the universe.

Allow me to conclude with one of the most famous quotations from

Don Juan Matus, and my favorite:

“For

me there is only the traveling on paths that have heart, on any

path that may have heart. There I travel, and the only

worthwhile challenge is to traverse its full length. And there I

travel, looking, looking, breathlessly.”

|