|

By John Pint

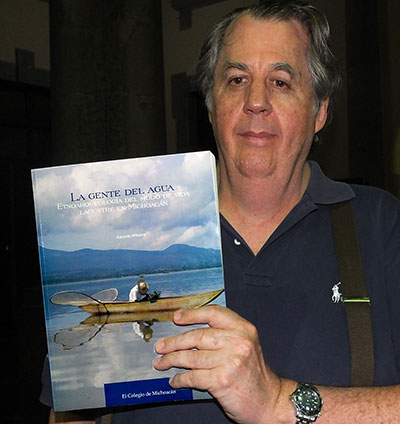

La Gente del Agua is a 416-page book, all in Spanish, representing

twenty years of study by Doctor Eduardo Williams of the “fishers”—as he

calls them, avoiding gender prejudice—who live on the shores of lakes

Cuitzeo and Pátzcuaro in Michoacán. Page through this book and you will

find hundreds of beautiful photos which suggest that this is not only

an impressive work of scholarly importance, but also a labor of love.

Fortunately for English speakers, Williams has produced a 165-page,

well-illustrated, abridged version of this book in excellent English,

which can be downloaded here from Academia.edu.

La Gente del Agua is a 416-page book, all in Spanish, representing

twenty years of study by Doctor Eduardo Williams of the “fishers”—as he

calls them, avoiding gender prejudice—who live on the shores of lakes

Cuitzeo and Pátzcuaro in Michoacán. Page through this book and you will

find hundreds of beautiful photos which suggest that this is not only

an impressive work of scholarly importance, but also a labor of love.

Fortunately for English speakers, Williams has produced a 165-page,

well-illustrated, abridged version of this book in excellent English,

which can be downloaded here from Academia.edu.

Williams’ study of modern-day people using the resources of these lakes

says much about the way the Tarascans lived in the same area before the

arrival of the Spaniards. This work is a response to a cry for help

made in 2001 by archaeologist Jeffrey Parsons in “The Last Saltmakers

of Nexquipayac, Mexico: An Archaeological Ethnography.”

Parsons says that

There are many traditional activities hovering on the edge of

extinction that deserve... recording in Mexico and throughout the

world. Few scholars appear to be much interested in studying the

material and organizational aspects of these vanishing lifeways, and

archaeologists may be virtually alone in making such efforts as do

exist. In one sense this… is a plea to others to undertake comparable

studies elsewhere while there is still a little time left to do so…

(Parsons 2001:xiv).

As Eduardo Williams points out, studies of this sort need to be carried

out by archaeologists, not by researchers in other social sciences,

because a certain sensitivity and attention to detail are required for

a highly specialized interpretation of the data, focused on how our

ancestors carried on similar activities. However, I think few

archaeologists have the patience to give so much of their time to a

contemporary society. For those who are willing to take up the

challenge, La Gente del Agua will be an admirable guide.

In the course of this research, the author of the book was surprised to

discover that one of the main tools used for manufacturing sleeping

mats (petates) and baskets from lake reeds, was identical to one

employed by the most ancient of our ancestors, possibly the oldest

known tool on earth. This was a flat, rounded rock that most of us

would pay no attention to whatsoever, unless neon signs were pointing

to it in a museum. These rocks, in modern times called petateras in

Michoacán, fit nicely in the hand and may be polished on the bottom

from being used to press and smooth moistened reeds as they are being

woven together. The only other tool needed to make a sleeping mat is a

knife (in ancient times an obsidian blade would have been used,

according to Williams).

The same people Williams found making petates also specialized in

waste-paper baskets, lampshades, cat baskets, decorative “Christmas

bells” and even human-like figures which surely must have required long

hours of patient work.

There are many gems hidden away in this large book. I was surprised

that Williams had found people living on the shores of Lake Pátzcuaro

who knew how to use the atlatl, the celebrated device for propelling a

spear much faster than it could be thrown by hand alone and one of

humankind’s first mechanical inventions (at least 10,000 years old,

according to archaeological data).

A fisher from Tareiro showing how the atlatl was used to hunt ducks in

Lake Pátzcuaro.

“In the late 1940’s, ducks by the millions used to arrive at Lake

Cuitzeo in early October,” fisher Manuel Morales told Williams, “and on

October 31 we used to go out in canoes to hunt them, with nothing but

fisgas, (reed harpoons) and el tirador (the atlatl).”

A second informant, Rogelio Lucas, offered to show Williams the

techniques for manufacturing an atlatl, which he refrerred to as a

tirador or tzipaki, even though he had not made one since 1978. He also

showed him how to prepare the metal point of the fisga and a special

insert at the other end which fits into the atlatl. Altogether, the

craftsman used thirteen different tools to make the two pieces,

including a hacksaw and a vise-grip. Ancient atlatl makers would have

had their own specialized set of tools (called an “assemblage” by

Williams) to produce the same result.

Another surprising fact I learned from this book was that insects are

still one of the important resources “fished” out of Lake Cuitzeo.

Moscos or bugs, like water boatmen and shore flies, frolicking on the

surface of the water, are caught during the rainy season in very fine

nets of a cloth called tul, still sold in Mexican markets under the

same name, for making bridal veils. “In a good season,” says Williams,

“between 50 and 60 kilos of bugs may be collected in a single day.”

While moscos are today used as bird feed, in pre-Hispanic times they

were an important source of protein and amino acids for human beings.

In the Basin of Mexico three types of lake insects, it seems, were

considered appropriate for human consumption, while all others were

thought of as “dirty.”

The edible insects were prepared to be eaten while still alive, because

people in those times thought they lose their nutritional value once

they are dried. Citing Jeffrey Parsons, Williams says that the living

insects were ground up in a metate and turned into a paste, into which

were mixed cilantro, onion, garlic, epazote (wormseed), chile and salt.

This paste might be served with vegetables, hens’ eggs or pieces of

meat. The mixture was cooked in a wet corn husk on a comal for half an

hour and might be served with tortillas as tacos. The “bug tamal” was

still being eaten by fishers that Parsons studied at the beginning of

the 1990s.

It seems Mexico’s People of the Water were extraordinary—on a worldwide

scale—for the intensity and extent of their exploitation of lake

insects and algae (Spirulina). However, little is known about the kind

of “markers” indicating these activities, that archaeologists should be

hunting for. By investigating the work of Mexico’s modern-day lake

dwellers, patient ethnoarchaeologists like Jeffrey Parsons and Eduardo

Williams are shining new light on ancient customs.

At the end of Williams’ book he says that

“Numerous traditional activities and manufactures have virtually

disappeared from the aquatic environments mentioned in this book…,

Because of the serious environmental problems affecting these areas, as

well as the rapid pace of cultural change, the current generation of

scholars may well be the last one that will be able to observe and

record a traditional lifeway which is reminiscent of the pre-Hispanic

past. This would be an irreparable loss for our understanding of the

ancient history of Mexico’s lakes, a watery realm in which fishers,

hunters and artisans earned their livelihood on a daily basis over

thousands of years. These were the men and women who took pride in

calling themselves the “water folk”.

|