DAHL ABULHOL: THE SPHINX

FROM CYBER SPACE TO INNER SPACE

The message was short but a real attention

grabber:

AN ARAMCO WILDCATTER SAYS HE

FOUND A HUGE HOLE NEAR AL-HARADH.

SIXTY METERS WIDE. NO BOTTOM VISIBLE.

KNOW ANYTHING ABOUT IT?

-- Bob Lebling

"This one message makes all the effort put into our web site

worthwhile," I told Susy as I fired an email back to Mr. Lebling, an

Aramco writer who may never have found us if it weren't for our

Saudicaves.com web-page bulletin board:

SUCH A HOLE COULD BE A CONTENDER FOR

BIGGEST VERTICAL CAVE IN SAUDI ARABIA.

TELL US MORE.

John

In no time at all, we got a reply from Mr. Lebling along with a digital

picture of the sinkhole entrance and the phone number of Qurian

Al-Hajri, the wildcatter who snapped the shot. I picked up the phone

and gave him a call.

"Mr. Lebling told me about your BIG dahl. Do you have

the GPS coordinates?"

"I am a bedu. I don't need a GPS. Aramco gave me one, years ago, and I

put it in a drawer where it still lies. But I'd be happy to meet you

and take you to the hole."

We immediately contacted our caving friends and set a

date for visiting Qurian's abyss and on December 21, 1999, we lugged

our four huge gunny sacks of caving gear out to the airport and flew

off to the capital . Thanks to Aramco World Magazine, which supported

this expedition and encouraged us all along the way, we found a fine

Budget Nissan Patrol waiting for us at the airport and off we drove

through Riyadh's light (thanks to Ramadan) traffic to Al-Kharj and then

east along the lonely road that skirts the northern limit of the giant

Rub Al-Khali desert. Here we found many of Saudi Arabia's "circular

farms" growing alfalfa for the cows of the Almarai and Alsafi dairies.

The next morning found us sitting in our 4WD on a lonely

desert highway over 1000 kms from Jeddah, but only 45 kms from the

lonely outpost of Al-Haradh,. Susy and I had spent the night shivering

in our little tent only to be woken up at sunrise by an interminable

procession of heavy Aramco vehicles lumbering along the network of rig

roads that crisscross the Ghawar oil field, largest in the world. But

when we poked our heads out to see what was making all the commotion,

we were amazed to find ourselves surrounded by a wall of white. A

pea-soup fog was the last thing we expected to see in the desert!

Precisely at 10 AM, Mike Gibson and Arlene Foss pulled

up at our meeting point, a GOSP (Gas Oil Separation Plant) just off the

highway. A few minutes later, a white Explorer appeared.

"You are John? I am Qurian. Nice to meet you. Yalla, yalla (Let's go)!"

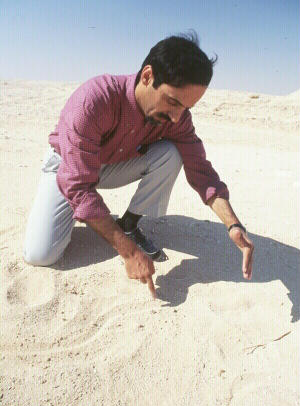

said the wiry man inside. Qurian led us through a maze of graded Aramco

roads, stopping occasionally to show us what the oilmen are doing in

the area. "This pipe with all the valves on it is called a Christmas

Tree. Oil was found here long ago, but only recently did we open the

valves to let it out. Now it's flowing through this pipeline. Can you

hear it?"

The pipe was humming, and hot to the touch. In Saudi

Arabia the problem is not pumping the oil out, but holding it down.

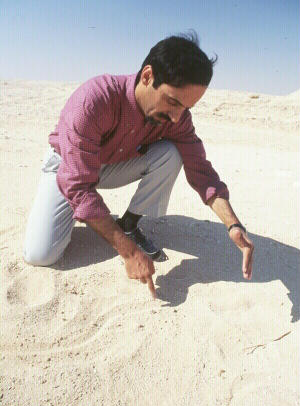

Beyond the oil field lay the empty desert whose most

salient feature was the lack of features. There wasn't even much sand

to be seen, just a hard, white, flat surface that stretched off in

every direction. Again I asked Qurian why he didn't use a GPS.

"Now I am very sensitive to the smallest details of my surroundings. I

have to keep myself razor sharp. But if I used the GPS, I would lose my

edge."

Curious about this man's outlook, we asked Qurian how

much of him was bedu and how much

Aramcoan.

"I am doing all I can to keep up the way of life I was

taught as a child. It was a hard life and made me strong. But today,

people have it easy and as a result, they are weak. So, I don't live in

Aramco housing - I live in a black, goatskin tent that was hand woven

by my mother, in the same lonely spot where my grandfather dug a well

long ago. You want to know how strong people were in the old days? I'll

tell you the story of how I was born.

"When my mother sensed that the time had come to give

birth, she slipped out of the tent and walked seven kilometers out into

the desert, to a place where no one could see her or hear her. You see,

she was shy and didn't want to disturb anyone. Maybe she was a little

embarrassed as well - it was the first time she was going to give

birth, you know.

"Well, after a while, I came out into her hands. That's when she

realized she had forgotten to bring along a knife to cut the cord with.

So she had to bite it in half with her teeth. Then she wrapped me in

her head scarf, slung me over her shoulder and walked the seven kms

back to the campsite.

"There she saw my father standing beside the tent. 'I

have a man for you,' she said, placing me in his hands. My father was

astounded. 'What? Didn't I see you a couple of minutes ago inside the

tent? How is this possible?'

"Now my father is dead and it's my responsibility to

care for my mother. And let me tell you, she still takes off a shoe and

whacks me when she has a mind to, but when that happens, I thank her

for her admonition and I kiss her on the top of her head, exactly like

a well-educated child should do."

With stories like these to listen to, time passed

quickly. Suddenly, about twenty kms into the desert, the dull white of

the landscape was broken by a circle of deep green. It was a round

wheat field irrigated by a slowly rotating pipe, sprinkling out

precious (and irreplaceable) eighteen

-to-thirty-thousand-year-old water pumped up from the aquifer deep

below.

This was obviously the landmark Qurian had been looking

for.

"The big hole is out in that direction," said Qurian through the open

car window. I'm 95% sure we'll find it."

Qurian drove off.

"What did he say?" asked Mike.

"Well, he's not completely sure where the hole is."

"That's what I figured," said Mike, ever the skeptic.

INTO THE BELLY OF THE GREAT SPHINX

We drove west, our cars three tiny specks on a vast white sheet, bright

and glaring in the afternoon

sun. For most of 50 kms I could distinguish no features that might be

helping Qurian to orient himself. How did he do it?

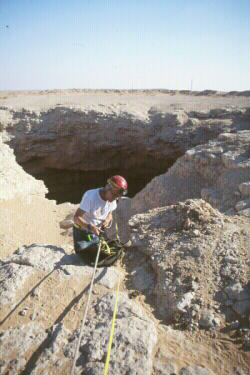

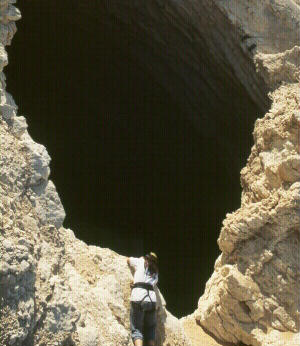

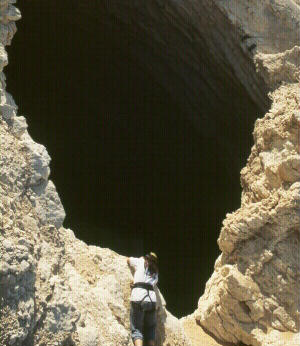

A half hour later, we saw a low, dirt rampart breaking

the monotony of the flat plain. Standing on top of the rampart, we

looked down into the mouth of a huge hole, a great, black scar

contrasted against the shimmering white of the desert. No bottom could

be seen. One glance and all our skepticism evaporated. Mike had figured

the hole would be "20 meters deep, tops" and I had gone for 30. Now we

were glad we had several hundred-meter ropes along. While we

circumnavigated the irregularly shaped chasm, looking for a good

rigging point, Qurian pulled out what looked like a briefcase and

opened it into a satellite phone which he used to contact his

headquarters. "Even though we're fasting for Ramadan and our office

hours are up, I'm always getting calls. Aramco never stops."

Then, out of nowhere, a pickup truck appeared and out

stepped several bearded gentlemen wearing dark "winter" thobes. They

were from Al-Hunay which would seem to be the closest settlement to

this hole - maybe 30 kms away. They seemed delighted that we had come

"all the way from Jeddah" just to visit this spot, which I presumed to

be the number one local attraction.

"We call this dahl "Abulhol" they told us, "because it's

BIG!"

"What does Abulhol mean?" we asked.

From their and Qurian's explanation, we gathered that

Abulhol was the name of a "very large and very ancient Egyptian." Only

later did we learn that this old Egyptian giant is actually the Sphinx!

After a while, the Saudis left, including Qurian who

urged us to come visit his tent at Ain Dar, where he had "one hundred

camels which Susy will enjoy milking for me."

When all the dust had cleared, we found

Arlene and Mike completely conked out, probably due to driving from

before sunrise. So Susy and I rigged the pit and then measured it. The

mouth was twenty by thirty meters, far short of Qurian's original

estimate of "sixty meters across." However, I'm now convinced that

great gaping maws in the desert appear so dramatic that the mind's eye

easily turns them into Egyptian giants. We, too, fell for this ruse of

nature, happy to believe for fifteen years that the Dharb Al Najem's

surface diameter was fifty meters, until we measured it in 1999 and

found it was only 25.

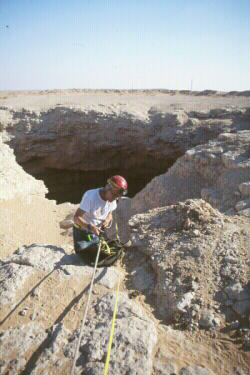

By now it was getting a bit late in the day for proper

exploration, but Mike had finally woken up and decided he'd like to do

a quick reconnaissance. What he hadn't figured on, though, was how

quickly he would get to the bottom on his new rope, which turned out to

be so flexible it offered almost no resistance to his rack (descending

device which depends on friction of the rope passing through removable

metal bars).

After recovering from his high-speed rappel,

Mike found himself on top of a very steep hill of sand in the middle of

a big, round room easily 100 meters across. We calculated the drop at

60 meters and the total depth at 70. This would give Abulhol the number

four position after the three deepest caves we know of in the Kingdom:

Ain Hit: About 150 meters

Dharb Al Najem: 100 meters

Abu Sukhayl: 75(?) meters

The next morning, Mike suggested we rig a second rope about a meter

from the first one, so we could get pictures of each other on rope.

]

About ten meters below the surface, Abulhol opens up into a huge, fully

illuminated single room, which gives you the feeling that you are

hanging in space, maybe the way you would feel if you were suspended

from a helicopter over an enormous canyon. As we dropped into the pit,

we found ourselves among hundreds of rock doves soaring across the vast

room, which was almost perfectly round. We landed on the steep hillside

at the bottom and scrambled down to where we could gaze at the huge

dome above us without fear of getting hit by debris from above. It was

a spectacular sight. The upper two-thirds of the room appeared to be

limestone while the lower part reminded me of the Dharb Al-Najem:

something like hard-packed dirt. This didn't look like a cave formed by

dissolution of limestone, but suggested to me that there had been a

large deposit of a soft mineral below the limestone level and when this

was dissolved away, there was an enormous collapse. If so, the sandy

floor on which we were standing may be far above the bottom of the

original hole.

About half the cave can be easily reached by walking

around the perimeter. The rest is covered by giant blocks of breakdown

which look very unstable. We moved along, looking for passages, but for

the most part only succeeded in surprising the doves that were

blissfully roosting on the floor. These birds would inevitably pop up

right in our faces, scaring us as much as we scared them.

Unexpectedly, we came upon a side passage in this wall

which did not appear to be of limestone. After seven meters and a

couple of turns, the little passage shrank in size, but went off in a

straight line. About eight meters ahead I could see an opening into

what seemed to be a large room. Teeny footprints had created a

well-worn highway in and out of the room, but the passage was too tight

for me to proceed ... and worse for Mike! However, the floor looked

soft and removable and I believe some valiant future explorers could

reach the distant room and perhaps learn something more about the

origins of Dahl Abulhol. Other features at the pit bottom included

truck tires, sand-filled soda bottles and numerous dehydrated doves.

Having turned up nothing more as regards passages or

formations and having thoroughly worn out our welcome with the doves,

we prepared our return to the surface. For this we use mechanical

ascenders which slide up the rope easily but hold tight when pulled

downward. As I prepared for my climb, I saw Mike stuffing our various

bags of photo gear and such into a giant duffle bag.

"Mike, that looks like the Abulhol of all gear bags.

Shouldn't we send up one bag at a time?"

"It'll be a lot easier (emphasis added by yours truly)

to do it all in one haul," were Mike's last words as I started up the

rope, and unforgettable words they proved to be.

Climbing the rope, I was persuaded that too much time

had passed since my last deep pit. Even though my Zotz Franco-Mexican

ascending system is (in my humble opinion) far superior to Mike's, I

still found myself sweating nearly as much as he was. Could it be that

I was out of shape?

By the time both of us got out of that hole, darkness

was fast approaching.

"Quick, let's get the gear bag up while we have light,"

I said, turning to Mike for instructions, ready to see some secret cave

diver's trick for lifting heavy gear. Mike leaned over the edge of the

great pit and tugged on the rope. "Argh! I can't even budge it. Guess

we'll have to rig a pulley system."

About a half hour later we had all of our pulleys and

all of Mike's in operation but when the four of us hauled on the rope

with all of our combined might, the infamous bag didn't rise one inch.

"Mike, it looks like something's wrong here. A Z-system

is supposed to make it easier to lift a weight, not harder."

"OK, I admit it's not working. Why don't we just attach

the rope to the car and..."

"Wait a minute - our video camera is in that bag! Let me

try a cave rescue system we used to use in Mexico." Well, it took an

hour to set up this clever arrangement (borrowed from the book ON ROPE)

which uses only three pulleys to give you an eight-to-one lifting

advantage. All four of us were then kept busy either pulling on the

rope or repeatedly returning various ascenders to their original

positions as the weight below slowly rose.

"OK, John," said Mike, "it's working, but we have to

pull ten meters of rope to lift the bag a couple INCHES. This is going

to take all night!"

I had to admit that that clever system does

have a few slight drawbacks, but we solved the problem by making one of

us "the mule" who would run those ten meters back and forth, hauling

the rope (which was easy to pull) again and again until he or she was

ready to drop. Then we'd appoint a new mule. In a mere two hours the

bag reached the lip and we celebrated our triumph with wild whoops,

declaring ourselves qualified and ready to pull the fattest camel out

of the deepest dahl, as long as nobody was worried about how long it

might take.

So ends the story of what what we suppose was the first

descent to the bottom of Dahl Abulhol. Half of the cave - covered by

giant chunks of breakdown - still needs to be checked for side passages

and on a return expedition, enthusiastic diggers may reach the end of

the Teeny-Footprint Highway and perhaps succeed in answering the last

riddle of Saudi Arabia's Great Sphinx of the Desert.

|