|

When Heiko Dirks and I visited Ain

Heeth (Ain Hit, Ain Hith, Ain Heet) February 19th, 2008, we

were able to descend into the lowest room

that had been explored by divers in 2002. At the time the water was

crystal clear and bluish (Fig. 1), thin calcite rafts were swimming on

the surface (Fig. 2) and we could study the dissolution features of the

cave, typical for dissolution of convecting water, i.e. sections of

flat solution ceilings with the typical solution cups (Fig. 3), smooth,

sloping side-walls, so called “Facets” (Fig. 4) and ragged protrusions

(Fig. 5). We even took a water sample (Fig. 6) that was accidentally

half drunk (in spite of clear labeling!) at a party the following

night. Luckily we had not poisoned the sample, as we might have done if

it had been destined for organic geochemistry.

According to the survey Gregg Gregory

and others made in December 2002 we must have been at a depth

146 m below the lip of the entrance, at that time the deepest

point reachable in a cave in Saudi Arabia. The northward

passage, explored by the divers was not yet accessible at that

time.

Fig. 1. The lake at the bottom of Ain Heeth in February 2008:

Fig. 2. Calcite rafts at the bottom of Ain Heeth, February 2008

Fig. 3. Solution Ceiling in Ain Heeth

Fig. 4. Sloping sidewalls, typical of density-driven convective

dissolution.

Fig. 5. Ragged protrusions (pendants) typical of hypogenic

convective dissolution.

Fig. 6. Water sampling in the clear ground water of Ain Heeth in

2008

We had heard from colleagues of Heiko,

who had made the trip down the cave a few month earlier, that

they did not see our water level mark left in 2008 (Fig. 7) and

they said that they did not enter a relatively low hall at the

end, but that the floor sank steeply below the water level.

Thus we were eager to return, to check

on the water level condition and take another water sample.

Opportunity arose on the afternoon of January 24th, 2011, after

I had given a talk about lava caves and the hydrological

potential of the Harrats at the Ministry of Water and Energy (MOWE)

at Riyadh.

We took some time out to use a new dirt road to drive

around above the escarpment and after following a few blind

leads, finally found the dirt road that leads to the

North-oriented embayment that harbors the entrance to the cave.

This time the dirt track runs through the gravel pit in front of

the embayment and is only passable with a 4WD, such as Heiko’s

Toyota. We parked about 60 m away from the lip of the entrance,

to be clear of any stones that might fall from the crumbling

walls of lower Cretaceous, platy rocks that surround the

embayment.

Fig. 7. Water level mark left by us in

February, 2008 at the bottom of Ain Heeth.

At about 4 PM we had helmet, camera

and backpack ready and approached the gaping entrance. From the

lip of the descent one formerly had a magnificent view down the

sloping passage (Fig.8), but now the view is obstructed by a

massive pile of fallen Cretaceous debris (Fig. 9). This collapse

of the western wall above the cave must have happened rather

recently because the stones looked very fresh and had not been

treaded on. Possibly the rain of a few days ago had dislodged

them. While we scrambled in (wisely keeping to the eastern side

of the cave mouth), more stones fell and tumbled down the slope,

just as happened to us on the way out, when stones kept on

coming down.

We

moved, accordingly, quite quickly downward, sometimes sliding together

with rocks, to get away from the vertical wall above us, when we

realized that also the Heeth Anhydrite, the famous Upper Jurassic

aquiclude of Saudi Arabia, had produced rock falls. These rocks are

more like boulders, the smaller a few 100 kg and the larger ones of

truck size. Where formerly a car wreck (however it got down here we

don’t know) (Fig. 10) rested, now big, newly fallen blocks covered it.

If this was one event or if these monstrous spars came down one by one

cannot be said, but their fall had generated ubiquitous dust, that

covered everything, including the garbage that reappeared in the deeper

parts of the descent that were not affected by collapse. As quickly as

possible we descended and came to the rocks where a rope hangs and that

lead to a small passage between blocks behind which is a larger room.

In this part the edges of the anhydrite blocks are quite polished from

people traveling. Many inscriptions “crafted” in industrial paint occur

here. Another climb and turn down brought us to a very steep decline

made of anhydrite slabs and below us, our helmet lights illuminated a

darker plane, the current water level.

Fig. 8: Opening of the cave in February 2008 (S. Kempe standing

in center; Photo by Dirks).

Fig. 9 Ain Heeth entrance partly filled with a new rock

avalanche.

Fig. 10 Formerly visible car wreck on the left side of the

descending Ain Heeth tunnel.

Fig. 11 narrow passage between rocks, marked profusely in case

one should get lost…

A light malodorous smell surrounded us

and when we stood at the water’s edge (Fig. 12), we noticed that

the lake was not only dotted with floating garbage but also was

covered with a grey bacterial slime, producing bubbles (Fig.

13). We were somewhat relieved to have Petzl LED lamps and no

carbide as in the old days, because the gas could easily be

methane. Heiko took – careful to avoid wetting his fingers – a

water sample and we made sure not to step or fall into this

slimy broth.

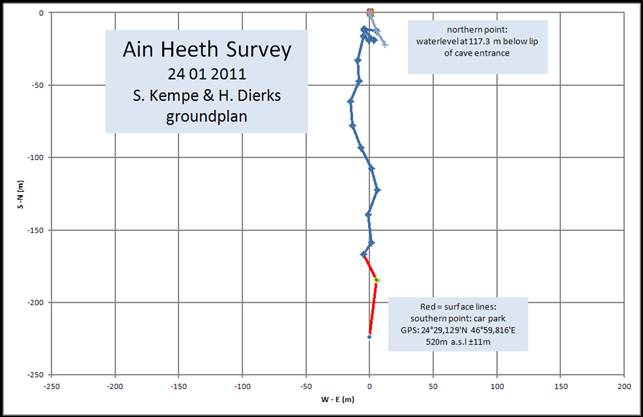

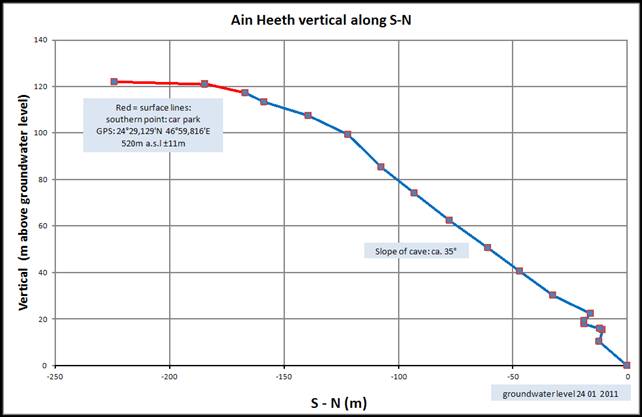

After taking some pictures of the

room we decided to survey back up to find out exactly where the

water table was now, because for sure it was now higher

(surprisingly) than in 2008 (Fig. 14 and 15). Seventeen stations

and 117.3 m higher we reached the exit at about 7 PM in the

dark. A pair of beady eyes had been watching our slow ascent

from the newly fallen rubble and the voice of the muezzin from

Kharj reverberated in the embayment as if in a large parabolic

reflector.

Comparing our data with that of the

survey of Gregg Gregory and co-workers from 2002, we encountered

the water table ca. 27 m higher than in 2008 at our first visit.

Two days later we heard from the Ministry of Water and Energy (MOWE)

that 7 km to the north, sewage from Riyadh is forming a lake

along the escarpment (see Google Earth). Thus Ain Heeth is

involuntarily providing us with a karst tracer experiment. At

this time it looks like the water table is going to keep on

rising and that trillions of bacteria are making a comfortable

living down there. Considering the filthy condition of the water

and the recent rock falls, the cave has lost its recreational

value, having turned into a very obnoxious and quite dangerous

place. I doubt that I will make that trip again…

Stephan Kempe, Darmstadt, January. 26th,

2011

Fig. 12. The water table on February 24th 2011 at Ain

Heeth.

Fig. 13. Bacterial slime and bubbles of gas (methane?).

Fig. 14. Ground plan of Ain Heeth

Fig. 15. Vertical section along South (left) – North (right)

projection.

|