THE JOY

AND

TERROR

OF CAVING

IN ARABIA IN THE EARLY DAYS

©2005 by John & Susy Pint and Will Kochinski

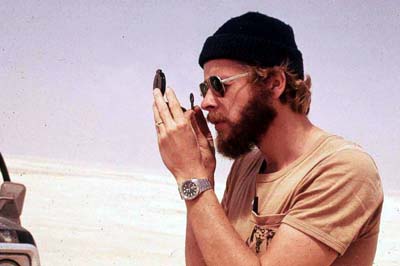

Taped interview with Aramco's Will Kochinski

by Saudicaves' John Pint on Oct 1, 2003, in Dhahran, Saudi Arabia

NOTE AND WARNING: Caves should not be explored without the use of helmets, lights, other appropriate equipment plus lots of training. We've learned a lot since the "early days" and you can profit from it all. We recommend you contact an organization linked to the International Union of Speleology for more information. Caves are dangerous!

SAUDICAVES: HOW DID YOU AND YOUR FRIENDS FIND YOUR WAY AROUND THE DESERT BACK BEFORE THE GPS?

WILL KOCHINSKI: In those days, we would use the triangulation stations that Aramco had established on various promontories and from these we would know exactly where we were...

We would set up a compass and one of the cars would take a direct bearing along the route and the other person would direct him with hand signals and we would go two or three kms, as far as we could, until the car was going to be out of the line of sight and then he would stop along the bearing and we would catch up with him and we’d repeat the process. We could navigate 20-30 kms on a dead line and that was the only way you could really find these dahls because the ones that were not well known or established were often impossible to see until you were right on top of them.

On these trips, we’d run into shamals, we’d get stuck, get rained on, our cars would break down… but these things are what made it fun and, of course, what really made it enjoyable was navigating by dead reckoning. It put a sense of adventure into all the trips. Sometimes you’d get lost and finding your way out was a lot of fun. That’s why, even though I have a GPS, I really don’t like them. They’ve taken away a lot of the exploration side of it. Before, when I was going camping, I would have studied the map; I would have paid very careful attention to my odometer, but also to the terrain. I would be looking at features like jebels (hills), wadis (dry river beds), kashams (outcroppings or promontories) and from these things on the maps I would be able to identify approximately or exactly where I was and it was a satisfying feeling to be able to do that. Now I find myself looking at that darned GPS instead of looking at the landscape around me and if the GPS broke down, I’d have to say, “How did I get here?”

I challenge anybody to leave their GPS at home and go find Jibu Al Kaliqa. I remember a couple times we went out there and we drove back and forth and could not find the thing. How you could miss such a big hole, I don’t know. It’s very cleverly masked by the terrain.

SAUDICAVES: JUST HOW BIG WAS THIS HOLE?

WILL KOCHINSKI: It’s an enormous pit, approximately 75 m across and you’re almost on top of it before you see it…

| ...and it surprises

me that cars haven’t fallen into it during the night. There’s a 10-15

m drop down to the bottom with cave entrances at both ends....

|

|

This is not a place someone can just come across and decide to explore. You may be able to get down it, but you’re not getting back up. We could see where somebody had piled up rocks trying to get out.

SAUDICAVES: SO HOW DID YOU GET IN AND OUT OF IT?

WILL KOCHINSKI: We had a rope ladder which was made of several hundred feet of discarded polypropylene rope…

SAUDICAVES: WHAT DID YOU LIKE ABOUT DAHL KALIQA?

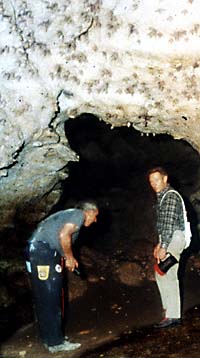

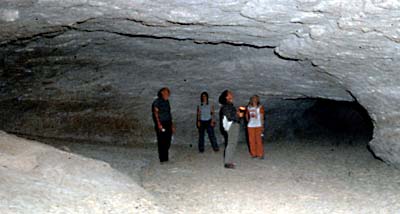

WILL KOCHINSKI: Well, just finding such a huge pit out in the desert was quite an adventure, but what I enjoyed was the cave itself. As I mentioned, it went off in two directions..

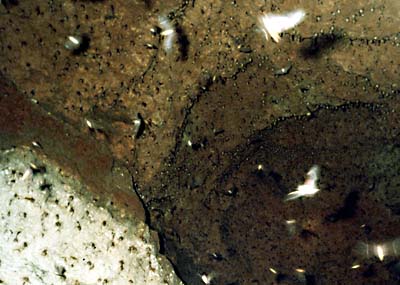

The bat cave was several hundred meters long and I remember looking up at the domes which were covered with bats hanging upside down and wondering just how thick was the crust… and at what point it’s going to cave in… and that thought made me wonder just where our truck was parked.

We took along a veterinarian once, into this bat cave. Well, there were hundreds, maybe thousands of bats in there and they sensed that people had come into their territory and they became agitated, flying around like crazy. And I remember standing deep in bat guano, climbing around and having a great time until the veterinarian casually mentioned something about rabies. So I said, “What? They might have rabies?”

“Oh yes,” he replied, “we’ve identified many bats with rabies – I’m sure glad I’ve had my vaccine!”

And after that, it was never quite so much fun to enter the bat cave.

| ...At the opposite

side of the pit were the subway tunnels. You could walk for a while and

then the roof eventually met the floor. You could see that the passage

continued but was silted up....

|

|

... It looked like it had once accommodated vast amounts of water to form these giant tubes and we considered digging to see it if was just a portion that had silted up and the passage might continue beyond that point.

SAUDICAVES: YOUR HOME-MADE ROPE LADDER MAY HAVE GOT YOU INTO DAHL KALIQA, BUT WHAT ABOUT DEEPER PITS?

WILL KOCHINSKI: Well, once we discovered a pit just north of Dahl Abu Sukhayl. It was a tube heading straight down for approximately a hundred feet. This was too deep for our rope ladder, so we rigged a system with an I-beam lying across the cave entrance, to which I’d welded a pad-eye or attachment point. From the pad-eye we suspended a block and tackle pulley system with four pulleys and a sling below the bottom pulley, which we would use to lower ourselves down. And I did that. I started lowering myself down, using this green clothesline that had been quadrupled as it went through the pulley system. But, unfortunately, about half-way down, because of the twist in the rope, the whole assembly took about 20 or 30 turns and froze.

Well, I couldn’t communicate very well with the people upstairs and I had myself a little problem but eventually we got it sorted out and I continued to head down to the bottom. Another problem was that the clothesline was so thin that it was impossible to grip with your hands, so I had to grip it with my fingers and it began to slip because my fingers were cramping… but the worst thing was that as I got near the bottom I realized that I had run out of rope.

So, there I was, holding on to this clothesline which I had now wrapped around my wrist because I couldn’t hold it with my hand anymore and it was completely cutting off the circulation and I was still 20 or 30 feet from the bottom and it looked pretty rocky down there…

SAUDICAVES: YOU COULDN’T GO UP AND YOU COULDN’T GO DOWN? SO WHAT DID YOU DO?

WILL KOCHINSKI: I started yelling! I was still spinning at this point and at the same time I was screaming to the people up top through this tube 80 or 90 feet long and they’re saying, “What? What? What did you say?”

Eventually I got them to understand that they had to take the rope and put tension on it so I wouldn’t fall to the bottom. So they start a discussion: “Which one is it? Is it this one or that one?”

Finally, I got to the bottom and I was never so glad to put my feet on the ground in all my life.

Later, another person came down to join me. Of course, we had to leave one person at the top to hoist us out, otherwise it was going to be hand over fist all the way back up, which would have been impossible. It was very dangerous and very stupid and I would never, ever, do something that that again. Fortunately, when you, Bruce Davis and other NSS cavers arrived on the scene, we learned the proper techniques for using caving rope and jumars.

SAUDICAVES: WERE THERE MANY OTHER PEOPLE EXPLORING DAHLS BEFORE WE CAME ALONG IN 1981?

WILL KOCHINSKI: The early Aramco pioneer in exploring dahls was Walter Dell’Oro who was here in the late 40’s and the 50’s, working in the Exploration and Geology department of Aramco and he had been all over the country in the days when there were almost no roads here. He had done a lot of this mapping and exploration on his own when Aramco was involved in basically mapping the entire country and he spoke Arabic well. He had as much fun finding these things as exploring them. You see, before we had GPS, the challenge was trying to find them. They were always very difficult to locate and there was always a sense of accomplishment when we identified another one.

I don’t think there’s a part of Saudi Arabia that Walt hasn’t driven to or at least driven past. We’d go out somewhere, to some innocuous looking piece of ground and Walt would say something like, “I remember back in 1946 when I was here …just over that hill there was a triangulation station.” And sure enough, there would be one.

Walt Dell’Oro thoroughly enjoyed exploring Arabia more than anyone I’ve seen. He’s now living in Santa Rosa, California. One of his compatriots was Dr. Bob Oertley. He was involved in various groups that go on outings, like the Natural History Society. In those days they would take Boy Scout Troops out to caves like Sabsab and they’d go down inside. Bob and Walt are the two people that took me along on their dahl explorations.

SAUDICAVES: WERE YOU INTERESTED IN CAVES BEFORE YOU CAME TO KSA?

WILL KOCHINSKI: No, I wasn’t. In fact, I can experience a sense of claustrophobia inside some of them, especially the close, foul-smelling, wet ones with soggy roofs...

It was dank, muddy, sloppy, potentially dangerous. And the Bedus, they thought we were touched for going in those holes. They were absolutely incredulous that we were doing this. They would say, “What are you doing? You need water? Here, we have water.”

Sometimes, when I’m down inside, you know, I ask myself, “Why are you really doing this?” I think it was the enthusiasm and motivation and perhaps the insanity of the other people that got me inside. I watched Walt doing it and I said, “If they’re going to do it, I’ll go down too.” But, if the truth be known, I would have just as soon stayed up on the surface… especially when you get down in there and run into a couple giant scorpion bodies and I ask myself, “Do I really want to be crawling in the fetid darkness?

Now, earlier, in my youth, I had done some cave diving and that was an absolutely terrifying experience. I didn’t enjoy that at all, so it surprised me that I actually went down into some of these caves. I think it was because it was a challenge. I enjoy finding them, I enjoyed the camping experience, being out in the desert, and then once you get there, why not go down inside? You might as well. They’re there, so you’ve got to go down.

SAUDICAVES: HAVE YOU DONE ANY CAVE DIVING IN SAUDI ARABIA?

WILL KOCHINSKI: None at all and I don’t plan to. You’ll understand why if you let me tell you just one story about a friend of mine who did go cave diving here.

His name is Mike Jones and he lives in Ras Tanura. Once upon a time, he went on a cave dive in Hofuf. They went down into a spring. Mike was following the guy in front of him. They had a safety line. Mike suddenly felt claustrophobic and turned around to go back outside the cave. As he went along, following his rope, he all of a sudden found the line disappearing into the ceiling. The rope was hanging from the ceiling just like a chandelier! So he looked around and could see no exit to the cave anywhere and he thought, “O my God, the roof has caved in and I’m trapped. I’m going to die here.” And he had to stifle the panic just to imagine how he was going to find his way out because he didn’t have a lot of air left. It was an absolutely terrifying experience for him. But eventually, he realized that the rope had cut through mud blocking the opening and he was able to track it back to a spot 20 feet away, which was the original opening he had come through. After he got out, he swore he would never, ever go into a cave again. The terror of it sits with him to this day and he still wakes up in a cold sweat after dreaming about being trapped in that cave.

SAUDICAVES: ON THAT PLEASANT NOTE, WE COME TO THE END OF THIS INTERVIEW WITH WILL KOCHINSKI WHOM WE THANK FOR HIS ILLUMINATING MEMOIRS ON DESERT CAVING IN THE GOOD OLD DAYS.

THE END