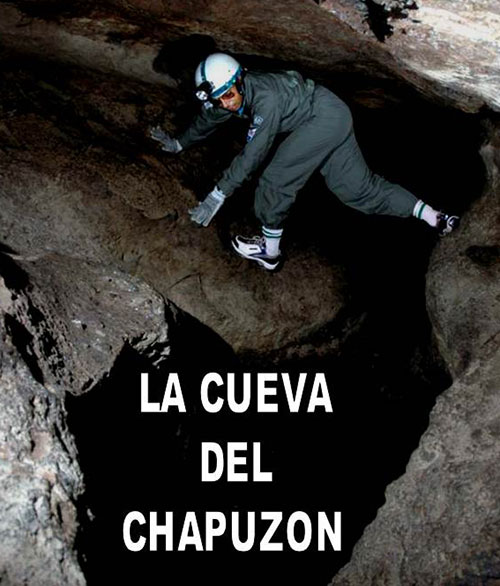

By John Pint

The closest cave to the city of Guadalajara is called la Cueva del Chapuzón, which we

first heard about one fine Sunday in May of 1988, in the plaza of the little

town of Ahuisculco, located 26 kilometers west of Guadalajara. This

being the hottest month of the year in these parts, the square was

already shimmering with heat, although it couldn’t have been earlier

than 10 am. We approached the stooped form of an octogenarian, relaxing on the

only shaded bench around. Tired eyes glanced at us from a face that

sported a harvest of wrinkles, perhaps from years of toil in the

burning sun.

The closest cave to the city of Guadalajara is called la Cueva del Chapuzón, which we

first heard about one fine Sunday in May of 1988, in the plaza of the little

town of Ahuisculco, located 26 kilometers west of Guadalajara. This

being the hottest month of the year in these parts, the square was

already shimmering with heat, although it couldn’t have been earlier

than 10 am. We approached the stooped form of an octogenarian, relaxing on the

only shaded bench around. Tired eyes glanced at us from a face that

sported a harvest of wrinkles, perhaps from years of toil in the

burning sun.

“Good morning, caballero, we´ve come here looking for caves in this

area. Could you help us?” This was my favorite technique—not very

scientific, I’m afraid—for finding caves in Mexico.

The ancient eyes grew puzzled. “¡Ay! If it’s caves you’re looking for,

you shouldn’t come to me. Why don’t you ask one of the old men around

here?”

Though we were unable to find anyone older than our venerable

informant, our question had been overheard by a rancher, young and

friendly, who claimed to have a cave on his own property. He was even

kind enough to draw us a map to the place, which resulted in our

standing knee deep in a muddy swamp about 45 minutes later, trying to

find a river, which would lead us to a waterfall which was close to the

cave. While slogging through the muck, little did we suspect that our

caving club, Grupo Zotz, was about to encounter one of its greatest

challenges.

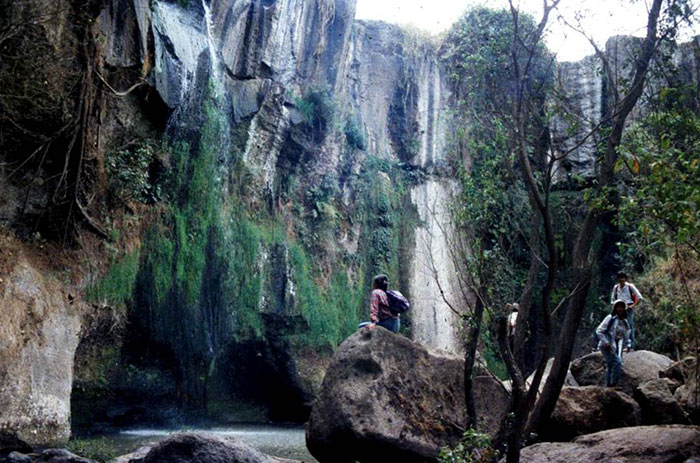

Eventually we reached the end of the swamp and what did we find but the

very river our informant had told us about. So, we began following it

downstream and after a while came to the top of a quite good-looking

waterfall, impressed by the accuracy of the friendly rancher’s

information. Now, all we had to do was find the cave.

Well, that problem was resolved, in a sense, the moment we reached the

very edge of the cascade, a strikingly beautiful one at that, with a

special plus for cavers. Standing at this spot, vapors rising from the

canyon some 20 meters below us reached our noses...and we gasped,

because, in spite of the sunshine and open air, we couldn’t miss the

unmistakeable, pungent odor of bat guano! “There is a cave after all,”

we said. “All we have to do is find a way down to the base of the

waterfall.”

"From the top of the waterfall we could smell the sweet perfume of bat guano."

As we had brought no rope, that job took several hours, following a

circular route which

brought us to the river at a point downstream. Then we had to wend our

way through a bamboo jungle to get back to the waterfall. When we

finally reached it, we could see a big black hole to the right of the

falls and we discovered that our cave entrance was completely flooded.

Naturally we made an attempt to “chimney” above the water level and

naturally we fell into the drink and this is how Cold Dunk Cave (El

Chapuzón) got its name.

This is the closest cave to Guadalajara and one of the most

interesting—as well as unusual—caves I have ever been in. It took us a

full year to discover that the cave has 623 meters of passages on two

different levels, with a small underground river running through most

of it. We also learned that Chapuzón Cave has seven entrances, most of

them much easier—and drier—than the waterfall entrance. Take a look at the Map of Cold Dunk Cave.

In the course of mapping the cave, our biggest obstacle was la Pila de

la Pestilencia, a gooey mix of bat guano and water, on the surface of

which bobbed the bloated body of a dead rat. Finding no way to get

around it, we finally decided to plunge right in and swim across.

In the course of mapping the cave, our biggest obstacle was la Pila de

la Pestilencia, a gooey mix of bat guano and water, on the surface of

which bobbed the bloated body of a dead rat. Finding no way to get

around it, we finally decided to plunge right in and swim across.

On a brighter note, Chapuzón Cave also has a spot we called the

Degollado Balcony, which brings you within a few meters of a very

lively colony of bats hanging from the 12-meter-high ceiling. A beam of

sunlight from a slot in the roof allows you to observe the bats

behavior while comfortably seated, with your feet dangling over the

edge of the “balcony.” It was fascinating to watch the social

interaction of one particular bat, (whom we named Lonesome George) with

the majority of the colony. George would keep trying to squeeze his way

into one of several huddled masses of bodies, only to be pushed out

again and again. For detailled reports on the exploration of La Cueva del Chapuzón, see Subterráneo number 2 and Subterráneo number 5.

Nani Ibarra, Chuy Moreno and Mano Ibarra during the first explorations of La Cueva del Chapuzón, in 1988.

|