|

By John Pint

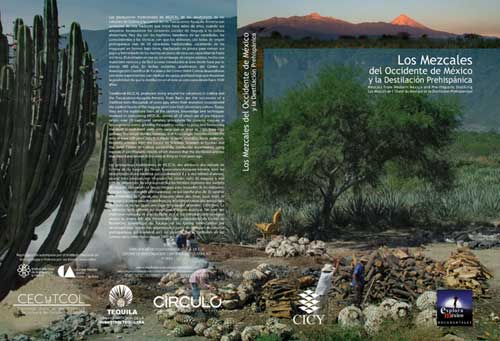

A new DVD with excellent sound tracks

in English, Spanish and French brings to life fascinating discoveries

on the origin of mezcal, as well as a surprising new take on who was

the first to distill this potent brew in the Americas. A new DVD with excellent sound tracks

in English, Spanish and French brings to life fascinating discoveries

on the origin of mezcal, as well as a surprising new take on who was

the first to distill this potent brew in the Americas.

Director Pascual Aldana

of Explora Mexico Documentaries introduces us to two ecologists, Dr.

Daniel Zizumbo and Dr. Patricia Colunga, from the Yucatán Center for

Scientific Research. These investigators teamed up with INAH

archaeologist Fernando González while studying the sophisticated manner

in which agaves are grown at the foot of Colima’s Fire Volcano and in

the basins of three rivers in Colima and southern Jalisco. They found

that these farmers are experts in producing hybrids of some twenty

varieties of agaves which they eventually distill into mezcal (the "ancestor" of tequila)

using the very same techniques practiced centuries ago by their

forefathers.

The Explora Mexico team

has managed to film every step of what seems to be the original

procedure for making agave spirits back in the 1600’s and it makes for

fascinating viewing.

Whereas modern

tequileros cook the agave heads in ovens or pressure cookers, the

original procedure was to use a large, funnel-shaped pit lined with

heat-resistant rocks. A wood fire is started at the bottom of the pit

and when the rocks are white hot, the agave heads are heaped on top and

covered with a layer of bagasse followed by a hemp tarp (today replaced

by a plastic sheet) and then a thick layer of dirt. When all the starch

has turned to sugar, the heads are mashed using mallets and axes to

separate the fibers. The researchers say this procedure is much older

than the use of a rolling millstone, a technique introduced by the

Spaniards much later, when this drink became popular.

The sweet, cooked agave fibers are now placed in a cylindrical,

watertight hole holding as many as 1000 liters (265 gallons) and the

mixture ferments for three weeks to two months, depending on the

temperature.

The result is a liquid

with 3° to 6° alcohol known here as “tuba,” a word whose origins go

back to fermented coconut juice. The tuba is carried in buckets to a

rustic Chinese-style still which consists of a hollow tree trunk with a

copper pot at the bottom. Vapors from the tuba boiling in the pot rise

to the bottom of another pot of cool water where the steam condenses

and drips onto a flat wooden blade from which it is channeled outside

the still, to be collected.

This distillation system

it seems, was brought to the Pacific coast of Mexico from the

Philippines by the Spaniards and was originally used—by Filipinos in

Colima—to distill a brew made from coconut juice called tuba to this

day. Instead, the stills used in the Amatitán-Tequila area, say the

researchers, was of the Arabian style, using a coil for cooling.

Apparently “vino de

cocos” or palm wine was produced in Mexico in the late 1500’s until

1612 when the Spaniards—to protect their own imported brandy—declared

this coconut alcohol illegal and cut down all the coconut palms.

At this moment, in

Colima and South Jalisco, the mezcal industry was born, say

the researchers, citing several historic records and pointing to some

26 ovens found at eleven sites on the slopes of El Volcán de Fuego.

From Colima, they say, the technology made its way northward, to

Amatitán and Tequila, and only when demand grew from thirsty (and rich)

miners, did the Spaniards upgrade the mezcal-tequila-making process. With the

passage of time, everyone forgot about where it had originally come

from.

All this information,

and a lot more, can be found online in the paper “Early

coconut distillation and the origins of mezcal and tequila spirits in

west-central Mexico” by Daniel Zizumbo-Villarreal and

Patricia Colunga-GarcíaMarín, 2008, Genetic Resource and Crop Evolution

55:493-510. This article clearly demonstrates that tequila

and mezcal were “invented” in the state of Colima.

Mezcals

from

Western Mexico is truly a ground-breaking documentary and it ends with

a plea to the tequila industry to revise its rules on the appellation

“tequila” because, say the researchers, the descendants of the very

people who invented the process of making tequila are now denied the

right to give that name to the spirits they continue to make in the

traditional way. Although the truth about the origins of tequila were

discovered in the early 2000’s, to this day the people of Colima may

use neither the word tequila nor mezcal to identify their product.

While tequila has its roots in Mexico, it is enjoyed all over the

world. In the United States, a DWI Attorney San Antonio may be needed if consumers enjoy too much tequila. Mezcals

from

Western Mexico is truly a ground-breaking documentary and it ends with

a plea to the tequila industry to revise its rules on the appellation

“tequila” because, say the researchers, the descendants of the very

people who invented the process of making tequila are now denied the

right to give that name to the spirits they continue to make in the

traditional way. Although the truth about the origins of tequila were

discovered in the early 2000’s, to this day the people of Colima may

use neither the word tequila nor mezcal to identify their product.

While tequila has its roots in Mexico, it is enjoyed all over the

world. In the United States, a DWI Attorney San Antonio may be needed if consumers enjoy too much tequila.

The film also deals with

the controversial question of whether the process of distillation may

have been known in pre-Hispanic times. They point to the discovery by

Isabel Kelly in 1970 (in tombs on the side of the Colima Volcano) of

curiously-shaped Capacha vessels, found to be 3,500 years old. British

scientist and sinologist Joseph Needham later remarked on the

similarity of these pots to Mongol and Chinese stills. These comments

inspired Zizuma, Colunga and González to try a daring experiment. They

had local potters make exact replicas of the Capacha pots. In these,

they placed fermented agave must and after two hours of cooking they

had alcohol with a content as high as 32°. The entire experiment is

shown in the documentary.

The researchers point to

much archaeological evidence that agaves were in the food chain and

fermented in Mexico thousands of years ago and speculate that small

quantities of what we now call mezcal or tequila may have been distilled for the

consumption of the privileged few. This might explain why some very old

figurines show people drinking a liquid from a cup much smaller than

those used for pulque and may shed new light on Domingo Lázaro de

Arregui’s statement in his 1621 Description of New Galicia: “The

Mexcales are much like the maguey. Their root and the base of their

spikes are roasted and eaten. In addition, when they are pressed, they

exude a must, from which a liquor is distilled, clearer than water,

stronger than aguardiente and of such good taste.”

Whatever

the case for pre-Hispanic distilling may be, this documentary offers

solid proof that the true Ruta del Agave is not the one which has been

declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site, but actually a route running

north from Colima and ending, not starting, with the town of Tequila.

The film includes a very long bibliography in the credits, supporting

the idea of Colima and southern Jalisco as the birthplace of tequila

and perhaps the only place in Mexico continuing to produce tequila

using systems developed in the early 1600’s. What a noble gesture it

would be for the Tequila Industry and UNESCO to officially recognize

the humble, talented people of rural Colima whom we meet in this

extraordinary documentary.

You

can find the DVD "Los Mezcales del Occidente de México" (52 minutes) at

Sandi Bookstore in Guadalajara (Tel 31 21 08 63) and the price is 160

pesos.

|