|

THE MYSTERY OF THE WHISTLING TEAPOT

John J. Pint

Copyright, 1999, 2009

Just getting to this place can be a harrowing experience. No matter how sturdy your vehicle is, a bouncing and jolting ride across scrubby hummocks and rocky pipeline "roads" can shear off shock absorbers and turn a solid iron tire rim into chewed-up scrap metal. And if it survives the pounding, you can be sure it will sink down to its axles in the treacherously loose sands of the Dahna desert, four-wheel drive or no. Then, once you have arrived on the plateau should the winds begin to roar, you may have to face the fierce fury of a full-blown sandstorm or shamal.

So what is it that would draw a group of city-dwellers out into such a formidable environment month after month?

Surely, as long as there is a square meter of our earth which has not yet been explored, it will attract adventurous souls, no matter the danger. And we already knew that underneath the drab surface of this plateau lay things which no man had ever seen, places where no footstep had ever been placed: the desert caves of Saudi Arabia.

"They have invited us for tea," said Husam Al Madkhali, an English teacher at Riyadh's prestigious Institute for Public Administration. He was referring to a group of Bedouins whose tent we had spotted on a desolate patch of sand in the As Sulb. A few minutes later, we found ourselves inside, eating dates and sipping sweet chai (tea). To our delight, we were seated among both men and women, the latter veiled, but fully participating in the conversation which could never have taken place without a fine translator like Husam.

"Where are you from? What are you doing here?" asked our new friends, while we, in turn inquired about the objects of our study: duhul (the plural of dahl), the natural wells which, we had long ago discovered, sometimes open into fascinating limestone caves.

"Have you seen any holes from which air is blowing?" we asked.

"You mean holes like the one right over there?" they replied with a smile, indicating a spot only a few hundred meters from their tent.

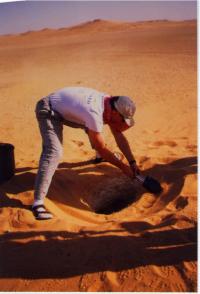

Minutes later we were carefully removing a rusty old barrel from atop a small opening only thirty-five centimeters in diameter. A strong gust of air blew sand up into our eyes. "It's another blowhole!" I shouted, recalling the drafty entrance to Dahl Sultan, a vast network of subterranean tunnels that we had been exploring for years. Could this small hole lead to another such labyrinth?

We carefully lowered a string with a lit flashlight at its end. As the light spun in the darkness, we could see there was a very large, empty space beneath us. The light came to rest on a sandy bottom about ten meters below. There was a cave down there, but the question was, could an adult squeeze through the narrow entrance tube?

Thirty-five centimeters only fourteen inches that's a very narrow hole and to make matters worse, it wasn't straight: we would have to wriggle past a sharp bend in the tube, which was over a meter long; too long to even dream about widening with a chisel.

We attached our cable ladder to the truck and I slipped into the opening. Surprisingly, the kink in the tube caused no problems as gravity helped me past it. But what would happen when I tried to get back up?

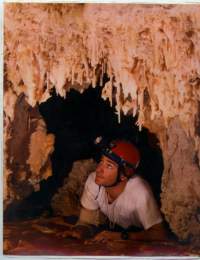

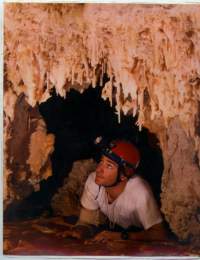

The cable ladder came to an end nearly a meter above the floor. I jumped off and looked around me. I was amazed. Every other dahl I had been in had wildly contorted, highly irregular walls. But those of this well-shaped room, which was nearly circular, were unusually smooth. There was no water in it, however, though there surely had been in the past. Now, only a few black beetles scurried about in the sand, trapped forever in the darkness. At last the beam of my headlamp came upon a triangular opening in the wall, maybe 75 cms high. The cave continued!

THE HOWLING

As I prepared to crawl into the small tunnel leading out of this room, I became aware of a very strange sound coming from wherever this passage led. At first, it was like a soft whistle, rising and falling. What it the world was that?

As I moved along the low, narrow passage, which almost seemed covered with whitewash, the whistling grew stronger until it was a wavering howl that brought visions of graveyards and banshees. Didn't they say that genies known here as jinns lived in caves? What lay at the end of the tunnel?

Little did I suspect, as I turned two sharp bends in the passageway, that at the end of it I would enter one of the most beautiful chambers I have ever seen in any cave. I turned the last corner and there they were, covering the walls and ceiling: hundreds and hundreds of shimmering, milky-white helictites. These are stalactites that defy gravity by twisting and turning in every possible direction as they grow.

The beautiful helictites looked very much like a company of ballerinas, frozen in the midst of an ecstatic dance. To add to the beauty of the scene, the floor of this room was covered with a smooth layer of rich, red Dahna sand which contrasted with the shining formations.

Nothing like this had ever been found in any other Saudi desert cave and I was delighted to point out my find to fellow caver Dave Black who had squeezed through the entrance hole and found me admiring that wonderful display.

There was, however, still the wailing of the banshee to deal with. We continued on, following the spooky noise until we found a small alcove at the very end of the cave. In its wall was a round hole about fifteen cms (six inches) wide, through which a strong wind was blowing with enough force to produce the strange sound that reverberated through the passages of the cave. It was a sort of natural whistle! However, while one mystery was solved, a new one was born, for beyond the small hole, the beam of my flashlight revealed an intriguing room. Were the thirty meters of passages we had found merely extensions of a much bigger cave that lay on the other side of that final wall? Was there any way we could get inside?

There was, however, still the wailing of the banshee to deal with. We continued on, following the spooky noise until we found a small alcove at the very end of the cave. In its wall was a round hole about fifteen cms (six inches) wide, through which a strong wind was blowing with enough force to produce the strange sound that reverberated through the passages of the cave. It was a sort of natural whistle! However, while one mystery was solved, a new one was born, for beyond the small hole, the beam of my flashlight revealed an intriguing room. Were the thirty meters of passages we had found merely extensions of a much bigger cave that lay on the other side of that final wall? Was there any way we could get inside?

Unfortunately, there was no time to dally, for it was getting late and we wanted to cross the treacherous sands of the Dahna while we still had light. However, in our enthusiasm, we had forgotten one small detail: would it be possible for us to squeeze back up and out of the hole we had come in?

I climbed the swaying cable ladder and soon had the upper part of my body inside the wickedly curving tube. My shoulders fitted the space entirely and I wondered how Dave Black, who is bigger than I am, had managed to get through it. I continued moving upward until I could see faces up above, peering at me. At that moment, I discovered a major drawback to cable ladders. If you are in a tight enough spot, there is no way you can lift your foot to take another step!

This was a very frustrating experience, being able to see the outside world, yet unable to reach it. Sheepishly, I grinned at Husam and, with some difficulty, raised one arm above my head. "Can you pull me out?" Instantly, several strong bedouin arms were thrust into the hole along with a few kilos of sand and I was lifted straight up into the air, coughing and sputtering, but free.

Dave Black was extracted in the same undignified but well-appreciated manner. Wiping the sand from his eyes, he suggested that next time we could rig a system of pulleys, by which each climber could extract him or herself, without the need for outside help.

Thus was born "Dave's Autohaul" and it proved a blessing on our further visits to the cave when no bedouins could be found in the area, our friends having picked up their tent and moved on.

The cave became known as the Whistling Teapot, since we had found it after drinking tea and since a "pot" is another name for a vertical cave. As for the whistling part, we couldn't forget that wailing orifice at the far end of the cave and the mysterious room beyond.

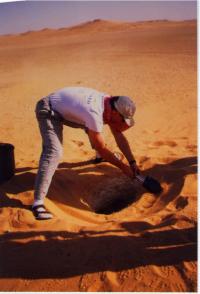

Since the floor of the cave is sandy, we figured it might be possible to dig a hole down and under the wall separating us from what we were calling the Closet of the Jinn. A French speleologist, Christophe Delestre and I would be the excavators while my wife Susy a Mexican would carry tools and messages from our outside support man, David Canning, an American caver of great experience and, alas, too great a girth to pass through the little entrance hole.

THE SAND SUMP

Perhaps if we had had some experience in escaping from prisons, we might have known how to dig a proper hole under a wall. We soon discovered you couldn't just go straight down one side and come up the other. The human body simply doesn't bend that sharply, even though we did our best to get Christophe through just such a siphon-like tube. Eventually we accepted the fact that we would have to dig a "bath tub" on our side of the wall, big enough to hold the trunk of a person in a prone position. This meant a whole lot more digging all by hand, since there was no room for a shovel and consequently swallowing copious amounts of the sand which was now fiercely blowing through the new hole we had made.

Eventually, all three of us wriggled our way under the wall and into the Closet of the Jinn. The walls of this little room were covered with flowstone of various colors and strangely contorted formations. It was a great place for a Jinn to hang out, but apparently he wasn't home that day. We did find, though, what may have been his lunch: the head and backbone of a small lamb with flesh still on the bones. Knowing no animal could have reached this room the way we had come, we realized that one of the many small passages leading out of the Closet must reach the surface. In fact, one such hole proved to be the source of the airflow moving through the whole cave, but, like the all the others, was too small for a person to fit through. Where all this air comes from we still don't know, but it seems possible that a very large cave system may still be awaiting discovery somewhere beyond the mysterious Closet of the Jinn.

Eventually, all three of us wriggled our way under the wall and into the Closet of the Jinn. The walls of this little room were covered with flowstone of various colors and strangely contorted formations. It was a great place for a Jinn to hang out, but apparently he wasn't home that day. We did find, though, what may have been his lunch: the head and backbone of a small lamb with flesh still on the bones. Knowing no animal could have reached this room the way we had come, we realized that one of the many small passages leading out of the Closet must reach the surface. In fact, one such hole proved to be the source of the airflow moving through the whole cave, but, like the all the others, was too small for a person to fit through. Where all this air comes from we still don't know, but it seems possible that a very large cave system may still be awaiting discovery somewhere beyond the mysterious Closet of the Jinn.

(Searches of the area have so far failed to turn up any caves obviously connected to the Teapot. Here is a challenging project for future explorers! Parts of this article appeared in

Return to the Desert Caves of Saudi Arabia, NSS News, November, 1997.)

|