|

|

© 2005 by John and Susy Pint -- Updated September, 2013

We moved to the

Guadalajara area of western Mexico in 1985 and the very first cave we

explored was located in the low hills above La Venta, the little town

closest to our new home. We were standing in the hardware

st ore

looking over hundreds of items hanging from nails on the wall:

everything from horse collars to hand-made, galvanized sprinkling cans.

While I was absorbed in selecting pipe fittings and the like, my wife

Susy stepped out into the street and exclaimed, "John, I can see a big

black cave entrance up there." Little did we suspect that what awaited

us in those hills was an enigma that would take ten years for cavers,

geologists, archeologists and historians to unravel.

ore

looking over hundreds of items hanging from nails on the wall:

everything from horse collars to hand-made, galvanized sprinkling cans.

While I was absorbed in selecting pipe fittings and the like, my wife

Susy stepped out into the street and exclaimed, "John, I can see a big

black cave entrance up there." Little did we suspect that what awaited

us in those hills was an enigma that would take ten years for cavers,

geologists, archeologists and historians to unravel.

We picked up our caving gear and made our way up rolling hills dotted

with oaks and pine trees to an impressive entrance seventeen meters

high and five wide. To our surprise, the cave walls were not of rock

but the hard-packed volcanic ash known as jal, from which the Mexican

state of Jalisco gets its name.

We stepped into a large,

single room in whose high ceiling we could see a perfectly round hole

about two feet in diameter. Not far from it, we found another very

similar hole. When we came upon a third such opening -- perfectly

aligned with the other two -- we knew there was definitely something

strange about La Cueva de La Venta. The room ended about 70 meters from

the entrance in an enormous collapse of loose jal, far too crumbly to

climb. Sticking out from under this huge heap, which nearly reached the

ceiling, was a pipe, from which water was trickling. Apparently the

cave continued beyond the collapse.

Upon the scene

came Henri de St. Pierre, a French geologist with whom we had caved in

Arabia. Henri, Susy and I headed up to the mesa above the cave. This

was a wide, flat area planted with corn and other crops. Here we

located the collapse, which, on the surface appeared to be a hole

twelve meters around and filled almost to the top with loose jal. We

started to walk away from the collapse and to our amazement, we found a

string of small holes, at first perfectly aligned and approximately 11

to 12 meters apart. We immediately began surveying and by the end of

the day counted 75 holes forming a gigantic Y on the mesa.

Upon the scene

came Henri de St. Pierre, a French geologist with whom we had caved in

Arabia. Henri, Susy and I headed up to the mesa above the cave. This

was a wide, flat area planted with corn and other crops. Here we

located the collapse, which, on the surface appeared to be a hole

twelve meters around and filled almost to the top with loose jal. We

started to walk away from the collapse and to our amazement, we found a

string of small holes, at first perfectly aligned and approximately 11

to 12 meters apart. We immediately began surveying and by the end of

the day counted 75 holes forming a gigantic Y on the mesa.

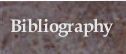

We plumbed one of the

holes and found it was about 22 meters deep. A rappel seemed the only

way to enter this part of the cave, but we wanted to have some idea of

what we might encounter down below: an underground river? a sea of mud?

"This," declared Henri, "we will clarify by casting down a probe." We

felt honored to participate in such a scientific approach to caving and

put together the required materials: a length of 1 inch pipe with holes

drilled at one end and a long piece of cord which is tied through the

holes. "Attention below!" shouted Henri as he dropped his missile down

the shaft. It made neither a clatter nor a splash when it hit bottom,

just a solid THUNK, so we watched in silence as Henri drew the pipe

back up to the surface. I had my camera ready to capture the historic

moment. What would the core sample reveal?

"This," declared Henri, "we will clarify by casting down a probe." We

felt honored to participate in such a scientific approach to caving and

put together the required materials: a length of 1 inch pipe with holes

drilled at one end and a long piece of cord which is tied through the

holes. "Attention below!" shouted Henri as he dropped his missile down

the shaft. It made neither a clatter nor a splash when it hit bottom,

just a solid THUNK, so we watched in silence as Henri drew the pipe

back up to the surface. I had my camera ready to capture the historic

moment. What would the core sample reveal?

Henri carefully examined the

end of the pipe and suddenly twisted his nose in revulsion. "Merde!" he

cried and suddenly there were no volunteers for rappelling.

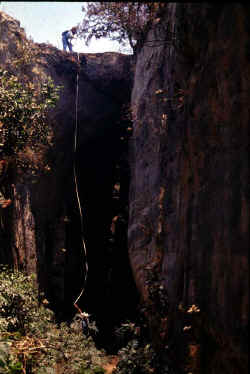

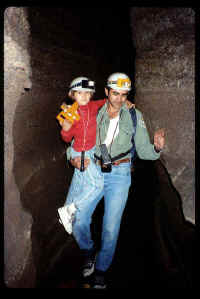

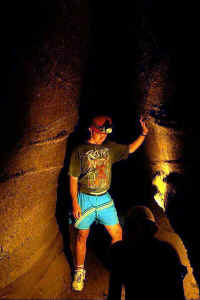

One day we returned to the

mesa and climbed down a cable ladder to the top of the great jal

collapse. A small opening between the cave roof and the dirt pile

revealed a long slope heading downward. Here was an easy way to check

out the main portion of the cave and a convenient escape route in case

we ran into anything disgusting. What we found was, once again, totally

unexpected. We were in a long, narrow, fissure-like passageway whose

floor was dry and which was anything but repulsive.

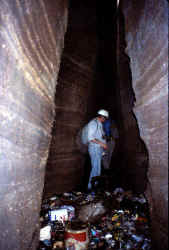

The scene before

our eyes was extraordinary. Through the curious holes in the high

ceiling shone beams of golden sunshine which deposited bright circles

of light on the dark floor. Suddenly, one of our friends on the surface

disturbed one of the holes and particles of dust floated down the

sunbeam, dancing like fairies and creating the illusion of a shimmering

white column appearing out of nowhere.

The scene before

our eyes was extraordinary. Through the curious holes in the high

ceiling shone beams of golden sunshine which deposited bright circles

of light on the dark floor. Suddenly, one of our friends on the surface

disturbed one of the holes and particles of dust floated down the

sunbeam, dancing like fairies and creating the illusion of a shimmering

white column appearing out of nowhere.

In this part of

the cave we found broken pieces of old-style water tubes and two

rectangular brick structures, all of which led us to believe that this

was -- as the local people asserted -- an old system for collecting

water and channeling it down to the village below. What we were not

prepared to believe was that the cave had been dug by human hand.

Instead, it seemed that the local people had taken advantage of a

natural fissure where water often collected. To bolster this theory,

our friend Henri had theorized that the roof holes could have been

caused by the intersection of the long, straight, natural fissure with

shock waves from a strong earth tremor, producing weak points where

surface water would drip, removing jal from the ceiling, one grain at a

time. To us it sounded plausible.

In this part of

the cave we found broken pieces of old-style water tubes and two

rectangular brick structures, all of which led us to believe that this

was -- as the local people asserted -- an old system for collecting

water and channeling it down to the village below. What we were not

prepared to believe was that the cave had been dug by human hand.

Instead, it seemed that the local people had taken advantage of a

natural fissure where water often collected. To bolster this theory,

our friend Henri had theorized that the roof holes could have been

caused by the intersection of the long, straight, natural fissure with

shock waves from a strong earth tremor, producing weak points where

surface water would drip, removing jal from the ceiling, one grain at a

time. To us it sounded plausible.

When two U.S. cavers, Ray and Cindy, visited Guadalajara, we naturally

wanted them to take a look at what we were touting as "the world's only

76-entrance cave."

When two U.S. cavers, Ray and Cindy, visited Guadalajara, we naturally

wanted them to take a look at what we were touting as "the world's only

76-entrance cave."

The three of us were on our way back from a visit to the nearby town of

Tequila when we decided to stop off at La Venta for a quick look at the

cave. Susy wasn't along and, in fact, seems to have a special talent

for not joining expeditions where disaster is poised to strike. On this

occasion, we had no proper caving gear with us, only one good

flashlight plus Ray's feeble throwaway, which was emitting a feeble

brown glow. "No hay problema," I exclaimed confidently as we made our

way down the dusty dirt pile, "there's plenty of light in this section

from all those holes in the ceiling."

The four-meter

wide fissure we were in quickly narrowed to a maximum of 1.5 meters at

shoulder level and a mere 30 cm on the floor. Right at a spot where

there was no shaft of light coming from above, Ray, who was bringing up

the rear, suddenly began yelling bloody murder at the top of his voice.

His shouts had such a tone of genuine panic that Cindy and I literally

leapt into the air and jumped forward while Ray jumped back.

The four-meter

wide fissure we were in quickly narrowed to a maximum of 1.5 meters at

shoulder level and a mere 30 cm on the floor. Right at a spot where

there was no shaft of light coming from above, Ray, who was bringing up

the rear, suddenly began yelling bloody murder at the top of his voice.

His shouts had such a tone of genuine panic that Cindy and I literally

leapt into the air and jumped forward while Ray jumped back.

Up until this moment, we had assumed there were only three of us in

that cave, but, from a point halfway between us, we could hear inhuman

noises that made our hair stand on end. "John, shine the flashlight

over there, down on the ground!" And we had our first look at the

creature with which Ray had been doing a tango in the dark.

There in that narrow slot, the bright beam of my light revealed the coils of a two-meter long snake, type unknown. It was obviously enraged, crazily striking left and right and putting on a terrifying show. As Ray so aptly expressed it, "That sucker was hissin' and' spittin' an' jumpin' all at the same time." And with good reason. Apparently, I had woken it up, Cindy had stepped right on it and Ray was left to make the apologies.

How

do you get past an incensed serpent in a narrow crack? Even when we

moved further away, we could see it lunging at every shadow. It had a

good 75 cm reach and there was no way we were going to slip by it. The

possibilities of chimneying up and over it were not too bright, for a

little experimenting showed us that one of the side walls was extremely

slippery.

How

do you get past an incensed serpent in a narrow crack? Even when we

moved further away, we could see it lunging at every shadow. It had a

good 75 cm reach and there was no way we were going to slip by it. The

possibilities of chimneying up and over it were not too bright, for a

little experimenting showed us that one of the side walls was extremely

slippery.

While Cindy and I pondered our situation, Ray left the cave to hunt up

a long stick. We decided he would used it to hold down the snake's head

while we zipped by. Cautiously Ray reached out with the pole... "Keep

the light on it, John! Keep the light on it!... Ah! Got him!"

There ensued a wild thrashing of rippling coils. Hoping Ray had the

right end pinned down, Cindy scrambled over, feet on one wall, hands on

the other. "EEEEEK!" I'm slipping!" It could have been a scene from an

Indiana Jones movie. However, Cindy didn't slip and I took a flying

leap, which resulted in my going right over the top of Ray, who was

squatting on the floor. Of course, as I flew over him, there was no

more light on the snake. "Run for it, Ray!" I shouted and believe me,

we didn't hang around to find out how fast that snake could move. Apart

from not carrying proper lighting, we had also failed to consider that

a cave with 75 holes in the ceiling is 75 times more likely to contain

extraneous objects than a single-entrance cave.

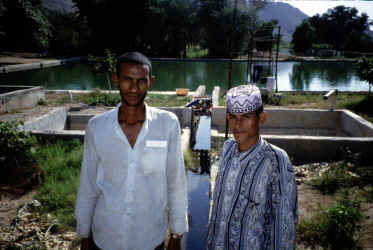

Feisty snakes are not the only things people like to toss into

holes in the ground. At the far end of the ever-narrowing passage we

came upon a great heap of trash on the floor. This was very close to a

ranch house up above and it seemed the ranchers had decided to use one

of those convenient holes as their garbage can. They were also using a

second hole as a toilet, but what they had decided to do with a third

hole really amazed us. Unbelievable as it may seem, they had run a pipe

down this one and through it they were pumping up the very water they

had contaminated. A large stone reservoir was their source of water

both for irrigation and for drinking.

For the next few years, we used the better-smelling parts of the cave

for training novices in rappeling and chimneying as we watched the

level of the floor fluctuate as much as one meter, depending on how

much water was flowing and whether or not it was damned up. There

seemed to be a battle going on between the ranchers on the mesa and the

people in the town and rumor had it that the collapse (which gradually

shrank as time went by) had been caused by dynamite. As for the true

origins of the cave, we were still in the dark until 1994.

This was the year that an archeologist named Chris Beekman walked into our house and introduced himself, saying he had been working in the jungles of Guatemala and -- when he mentioned he would be going to Guadalajara -- had been told to drop in on the Pints. How he ever found us, without a phone number or an address, in a city of six million, is a mystery to me, but apparently a trifle for an archeologist. In no time we became friends and enjoyed following Chris through the underbrush of desolate canyons and mesas. "Look at this!" he would shout, eyes aglow. "This was a corral and here are the foundations of a house." I would look as hard as I could at where he was pointing, but somehow, I never saw anything more than a few old rocks.

One day, it occurred to us to take Chris to La Venta Cave. An archeologist, we figured, might just spot something that a caver wouldn't notice.

Chris Beekman walked up to the cave entrance and stopped dead. "Look! Flat-edged pick marks! They go right up the walls to the top. This is a man-made tunnel!" Trying to hold our own, we pointed at the ceiling. "Check that out. It's a hole that only goes partway up and stops. It must have been a drip hole that dried up, proof that erosion..." but Beekman cut us off. "Wait a minute. Take a look at one of your completed holes. If it was 'naturally eroded' what are all those hand and foot holds doing there?"

We didn't have to get very far into the passage before we

threw in the towel. Everywhere, our "cave" showed signs of having been

carved by human hand, signs that even a non-archeologist couldn't miss

(once pointed out).

But the whys and wherefores of this curious underground passage fully

came to light when Beekman and I returned to the cavern with Phil

Weigand, an archeologist with many years of experience in Mexico.

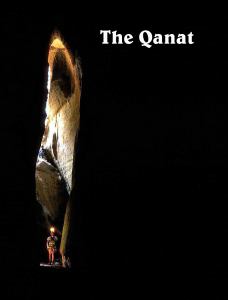

This is neither a cave nor a mine," declared Weigand. It is a

well preserved qanat and it is going to provide a major contribution to

our knowledge of such irrigation systems in the New World... in fact,

until now, no other qanats were known to exist in western Mexico."

Now, qanat is an Arabic word, which means that the first letter is not

like our "qu" but represents a kind of glottal stop you should make as

far down your throat as possible. If this makes you feel like you're

choking rather than talking, just say "ka-NOT". But what was an Arabian

qanat doing in Mexico?

In a paper written for the Mexican Anthropology Society, Weigand

explains that a qanat or kariz is a subterranean conduction device for

bringing water from one place to another. One end of the gently sloping

(about two degrees) tunnel is located beneath the water table, often

below the surface of a hill, while the other end reaches a community

where water is scarce or not available at all. The string of shafts is

dug to provide ventilation, light and easy access for excavating and

later maintaining the qanat. Once the system is operating, the holes

are sealed with capstones, several of which were soon found alongside

the shafts on the mesa overlooking La Venta.

Some historians postulate that qanats have their origin in Armenia,

where tunnel digging for mining is extremely ancient. Qanat

engineering, however, was brought to perfection in Persia, and modern

Iran still has over 160,000 kms of qanats, the longest system

containing some 27 kms of tunnels. This technology was spread far and

wide through the Middle East and Africa and is thought to have been

brought to Mexico by the Spaniards, who may have received the

techniques from Morocco. Weigand relates that qanats have been

described in several parts of Mexico, including the Tehuacan valley,

Tlaxcala and Coahuila.

While living in Saudi Arabia in the late 1990's I learned that qanats

were widely used there in the past and that the technology is still

greatly appreciated and applied in modern times. Underground aqueducts

would appear to be ideal for hot, desert lands where

e vaporation must be

kept to a minimum. There is even evidence that a qanat once saved the

city of Jeddah from invasion by Portuguese warships in 1516 AD. The

Portuguese believed they had cut off Jeddah's water supply and waited

in vain for capitulation, little suspecting that a qanat sixteen

kilometers long was supplying the town with all the water it needed.

vaporation must be

kept to a minimum. There is even evidence that a qanat once saved the

city of Jeddah from invasion by Portuguese warships in 1516 AD. The

Portuguese believed they had cut off Jeddah's water supply and waited

in vain for capitulation, little suspecting that a qanat sixteen

kilometers long was supplying the town with all the water it needed.

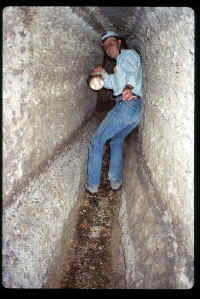

Just how did the qanat builders go about excavating their underground irrigation system? In a paper submitted to Mexico's Collegio de Jalisco, Chris Beekman describes the techniques used by Persian professionals:

The master digger decides where the mother well (a misnomer as this is not actually used as a well) should be dug. This vertical shaft is dug at or near the top of an alluvial fan and is meant to determine the depth of a permanent and reliable deposit of ground water. Once this depth is reached, a calculation can be made as to where the mouth of the channel should be located and, hence, how much land can be irrigated from the projected qanat. If deemed desirable, the excavation of the channel can begin... Shafts between the source and mouth of the system can be started either before or at the same time as the excavation of the tunnel. Armed with picks, shovels, baskets and small lamps, the diggers begin either to link up wells and/or extend the tunnel from the mouth toward the mother well.

As the channel is small, the master digger does most of the actual excavation, aided by a few workers behind him to haul away the spoil to the nearest shaft. On the surface, other workers haul up the spoil from the excavation below, depositing the material in a circle or crescent around the shaft's entrance, which keeps surface water from running into the hole. The shafts are often dug ahead of the channel's course, thus immediately facilitating both access and air flow into the tunnel as it progresses toward the mother well. Shafts are spaced from 15 to 150 meters apart (though always at fairly regular intervals) and are most frequently less than a meter in diameter. The deepest ones are over 100 m.

String alignments and levels are all that most master digger engineers

need to keep the channel at the correct angle of incline, the maximum

gradient being around 1:1000 to 1:1500 meters, and thus nearly

horizontal. Channels are kept as straight as possible to facilitate

both the construction and water flow, once the qanat is completed. The

tunnels are seldom more than one meter wide and 1.5 meters high and

their ceiling is arched to help prevent collapses. Aside from cave-ins

and suffocation, the most dangerous moment for the excavator comes when

the water table is actually entered. Flooding is then added to the list

of hazards.

String alignments and levels are all that most master digger engineers

need to keep the channel at the correct angle of incline, the maximum

gradient being around 1:1000 to 1:1500 meters, and thus nearly

horizontal. Channels are kept as straight as possible to facilitate

both the construction and water flow, once the qanat is completed. The

tunnels are seldom more than one meter wide and 1.5 meters high and

their ceiling is arched to help prevent collapses. Aside from cave-ins

and suffocation, the most dangerous moment for the excavator comes when

the water table is actually entered. Flooding is then added to the list

of hazards.

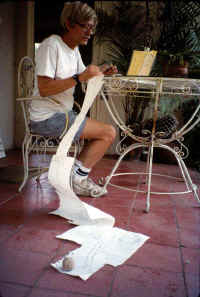

Studying

aerial photographs, Chris Beekman estimates that La Venta's qanat

system was originally 7.8 kilometers long, representing a radiation

network meant to tap ground water from at least three sources and

conduct it to an old estancia at La Venta where it probably played a

major role in the early agriculture of the area. He calculates that up

to 160,000 tons of jal (enough to fill the sumptuous cathedral of

Guadalajara to the roof) were removed, most of it caused by the tunnel

floor being lowered or eroded over the years. Water from the qanat

would have allowed year-round farming in an area with a six-month dry

season, where the water table is fairly low and the porous jal soaks up

surface water like a sponge. This particular qanat could be a good 400

years old, since Guadalajara was founded in 1540.

Studying

aerial photographs, Chris Beekman estimates that La Venta's qanat

system was originally 7.8 kilometers long, representing a radiation

network meant to tap ground water from at least three sources and

conduct it to an old estancia at La Venta where it probably played a

major role in the early agriculture of the area. He calculates that up

to 160,000 tons of jal (enough to fill the sumptuous cathedral of

Guadalajara to the roof) were removed, most of it caused by the tunnel

floor being lowered or eroded over the years. Water from the qanat

would have allowed year-round farming in an area with a six-month dry

season, where the water table is fairly low and the porous jal soaks up

surface water like a sponge. This particular qanat could be a good 400

years old, since Guadalajara was founded in 1540.

So successful was this unusual irrigation system that, according to a

local rancher, around the year 1911, water from the qanat was still

being channeled down to a cistern -- still to be seen alongside the

railroad tracks at La Venta -- to fill the boilers of early steam

engines.

As a result of cooperation between cavers and archeologists, local

historians have become interested in sifting through old records for

information that might indicate who built the qanat and when. They have

also expressed interest in cleaning it out and protecting it. Should

they succeed, the day may come when even tourists will enter that

curious passage to gaze in awe at the shimmering columns of light

piercing the darkness of the ex-cave we now call Qanat La Venta.

Parts of this article appeared in the NSS News, October, 1996, pp.

227-282. For more information on qanats in Mexico, see Old World

irrigation technology in a New World context: qanats in Spanish

colonial western Mexico by Christopher S. Beekman, Phil C. Weigand

& John J. Pint, ANTIQUITY, Volume 73, Number 289, June 1999,

pp. 440-446.

John J. Pint