THE ROSES OF TAIF

Before leaving my native Mexico for Saudi Arabia, I read an article

about roses being cultivated outdoors in the western part of the

country, in Taif. Although I knew there were a variety of agricultural

projects in that general area, I was still fascinated by the very idea

of Roses in Arabia. In my mind I could not picture flowers being raised

in a harsh and dry climate, at least not as easily as they are in

countries where nature lavishly assists just about anything you want to

grow.

My husband, John,

by then, had gotten a contract to work in Jeddah, which is relatively

close to Taif, and I was eager to join him before April, the main month

of the year when rose buds bloom only at dawn, making it easy to pick

them at precisely the right moment. Their marvelously scented oils are

then transformed into rose water from which attar, a highly appreciated

perfume, is obtained. Yes, I wanted to be a witness to what I

considered to be a magic phenomenon. My husband, John,

by then, had gotten a contract to work in Jeddah, which is relatively

close to Taif, and I was eager to join him before April, the main month

of the year when rose buds bloom only at dawn, making it easy to pick

them at precisely the right moment. Their marvelously scented oils are

then transformed into rose water from which attar, a highly appreciated

perfume, is obtained. Yes, I wanted to be a witness to what I

considered to be a magic phenomenon.

One afternoon in

the middle of April, my husband, and our two good friends, John and

Maggie Jenkins, drove up the spectacular escarpment which leads to

Taif. The Jenkins knew the caretaker of one of the rose farms, and they

had invited us to come along. We were following the Jenkins in our own

vehicle, a hardy Blazer stuck (by the former owner) with the unlikely

name of Petunia. At the very top of the escarpment, a gang of furry

baboons, including some mothers carrying their babies, looked at us as

if they expected every visitor passing that way to give them a treat.

We couldn't join the people who stopped to feed them or to look at them

because the Jenkins had warned us about the many twisting dirt roads

which we would have to take in order to reach the rose farms. "And

there'll be a few mountains to go over as well", they told us. One afternoon in

the middle of April, my husband, and our two good friends, John and

Maggie Jenkins, drove up the spectacular escarpment which leads to

Taif. The Jenkins knew the caretaker of one of the rose farms, and they

had invited us to come along. We were following the Jenkins in our own

vehicle, a hardy Blazer stuck (by the former owner) with the unlikely

name of Petunia. At the very top of the escarpment, a gang of furry

baboons, including some mothers carrying their babies, looked at us as

if they expected every visitor passing that way to give them a treat.

We couldn't join the people who stopped to feed them or to look at them

because the Jenkins had warned us about the many twisting dirt roads

which we would have to take in order to reach the rose farms. "And

there'll be a few mountains to go over as well", they told us.

"Will we be

needing four-wheel drive, then, John?" we asked, a bit nervously,

because we had been warned that ours wasn't working properly.

"Not to worry,"

replied our friend, "the roads are a bit rough, but if it looks like

you can't make it, we'll just carry on in our vehicle."

They were right

about the rough part. We had just entered the outskirts of Taif when

the Jenkins took a paved road which led up into the mountains and

suddenly ended. Then we started following a dirt road which rose and

fell and curved this way and that. At first, this road was quite nice

and we hoped it would continue like that so we would not even have to

think about four wheel drive. To our dismay, though, the road started

getting really rough and, at some point, we realized we were perched on

top of a high hill from where we could see a town way down below. Yes,

we would have to go down there and cross the town in order to continue.

"Hang on, Petunia!", we cried. Seeing the Jenkins bouncing happily

among all those big rocks with their Jeep didn't encourage us much, and

my stomach developed multiple cramps as the road got even rougher when

we began the steep descent. At this point, there was not a positive

thought in my mind.

Suddenly, the Jenkins stopped to talk to someone who was

driving a pick-up truck which was working its way up the steep slope.

"What!... Are we seeing things?" I asked my husband. But it was true:

it was a simple Toyota pick-up! This, I must say, did give us new

hopes... which were quickly dashed the moment we entered a very narrow

stretch of road along the mountain side. Here we found rocks even

bigger than the ones we had laboriously succeeded in passing. We were

convinced that that a simple pick-up could not have gone down this

road, and much less up it. No way! And we were also convinced it was

time to throw Petunia into four wheel drive, whether it worked or not,

because otherwise we would have to turn around and go back -- a mighty

dangerous proposition on that narrow ribbon of road. We were lucky: The

4WD low gears engaged and suddenly Petunia began to lumber along like a

powerful, unstoppable tank. So, we continued, now far more confidently,

following a road which at times was so narrow that Petunia had to

scrape along the side wall to keep us from plunging to the bottom of

the gully.

We finally saw

the first rose fields nested among the wadis protected by the

mountains. The dark green bushes were covered with tiny pink buds of

Rosa damascena trigintipetala --known as ward taifi to the locals--

which were waiting to open up the next day, before the sun's rays

diminish the oils which contain the esence of their perfume. A soft

breeze was blowing, filling the atmosphere with the pleasant aroma of

the flowers. This idyllic scene completely changed my state of mind.

From that moment on all I concentrated on was absorbing the beauty

which the rose farms had added to the already magnificent mountain

panorama ever since the rose farming began, three centuries ago. We finally saw

the first rose fields nested among the wadis protected by the

mountains. The dark green bushes were covered with tiny pink buds of

Rosa damascena trigintipetala --known as ward taifi to the locals--

which were waiting to open up the next day, before the sun's rays

diminish the oils which contain the esence of their perfume. A soft

breeze was blowing, filling the atmosphere with the pleasant aroma of

the flowers. This idyllic scene completely changed my state of mind.

From that moment on all I concentrated on was absorbing the beauty

which the rose farms had added to the already magnificent mountain

panorama ever since the rose farming began, three centuries ago.

It was late

afternoon when we arrived. The idea was to camp near the farm we were

visiting and the next morning, at dawn, of course, we would get up to

help the Jenkins' friend to collect the new roses of the day.

The stars were

still sparkling through the dark mantle of night when we started

walking toward the farm. When we arrived at the place where we would

meet the rose farmer, my husband and I looked at each other with

amazement when we noticed that the vehicle parked in the farm was the

very same Toyota pick-up we had seen the day before, and their friend

was the very same driver. "It cannot be possible!... Those pick-up

trucks must be magic!", we cried with chagrin.

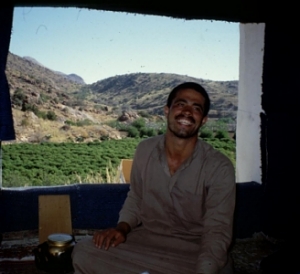

Ali abd al-Hamid

was the name of the farm's caretaker and he was already at work when we

arrived. He was a lively young man with a broad smile and he seemed

delighted to see us. Ali passed out baskets in which we would place all

the roses we could pick before 9:00 AM, when they had to be taken to

the al-Gadhi plant, where we were invited to observe the distillation

process. Ali abd al-Hamid

was the name of the farm's caretaker and he was already at work when we

arrived. He was a lively young man with a broad smile and he seemed

delighted to see us. Ali passed out baskets in which we would place all

the roses we could pick before 9:00 AM, when they had to be taken to

the al-Gadhi plant, where we were invited to observe the distillation

process.

As soon as the

first rays of the sun had touched the roses, the bees began their daily

job of pollination. It was quite a strange feeling to work in

competition with them, going from one rose to another for a very

different purpose. And I must say I felt bad about taking away the

bees' source of food as well as plucking such beautiful and delicate

flowers from what, up to that moment had been their source of life.

However, when I saw a basket full of them and I caught the scent of

their amazing perfume, I could not stop myself from picturing them in

my mind being transformed into rose water and attar --from Arabic 'itr,

"essence" or "perfume"-- which have been used for centuries in so many

countries. And then I had a lovely inspiration: "those roses were

destined to live for many many years and to make many people happy." As soon as the

first rays of the sun had touched the roses, the bees began their daily

job of pollination. It was quite a strange feeling to work in

competition with them, going from one rose to another for a very

different purpose. And I must say I felt bad about taking away the

bees' source of food as well as plucking such beautiful and delicate

flowers from what, up to that moment had been their source of life.

However, when I saw a basket full of them and I caught the scent of

their amazing perfume, I could not stop myself from picturing them in

my mind being transformed into rose water and attar --from Arabic 'itr,

"essence" or "perfume"-- which have been used for centuries in so many

countries. And then I had a lovely inspiration: "those roses were

destined to live for many many years and to make many people happy."

When we had

picked all the buds we could find, we took a short hike to the edge of

the steep, rugged, Harithi escarpment where an ancient camel trail --or

what remains of it-- winds its way down through flowers, bushes and

tall waving grasses to the canyon floor, thousands of feet below. The

magnificent view was framed by towering pinnacles of rock and all we

could do was stare in awe and click our cameras. When we had

picked all the buds we could find, we took a short hike to the edge of

the steep, rugged, Harithi escarpment where an ancient camel trail --or

what remains of it-- winds its way down through flowers, bushes and

tall waving grasses to the canyon floor, thousands of feet below. The

magnificent view was framed by towering pinnacles of rock and all we

could do was stare in awe and click our cameras.

Then we joined

Ali for tea, during which he regaled us with tales of battles fought to

protect his precious roses from porcupines and baboons. Then we joined

Ali for tea, during which he regaled us with tales of battles fought to

protect his precious roses from porcupines and baboons.

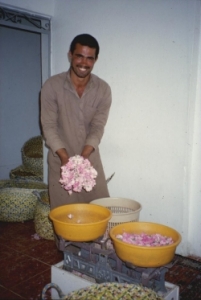

The visit to the distillery in Taif was the next

exciting chapter in our adventure. Just inside the entrance of the

factory, there were two people with scales since the quantity of roses

is normally calculated by weight. Inside, several other people were in

charge of carrying out the distillation process. There were several

tin-lined copper pots which can hold about 50 liters of water each.

The process of

distillation is, really, very simple. To those 50 liters of water

aproximately 10,000 roses are added. The pot is then tightly sealed

with a cover which looks like a mushroom-shaped hat. This mix simmers

for six hours. The steam collected goes through a tube which passes

down through a pool of cold water and ultimately reaches a large glass

jar called al-Arousa, where the rose water is collected. The process of

distillation is, really, very simple. To those 50 liters of water

aproximately 10,000 roses are added. The pot is then tightly sealed

with a cover which looks like a mushroom-shaped hat. This mix simmers

for six hours. The steam collected goes through a tube which passes

down through a pool of cold water and ultimately reaches a large glass

jar called al-Arousa, where the rose water is collected.

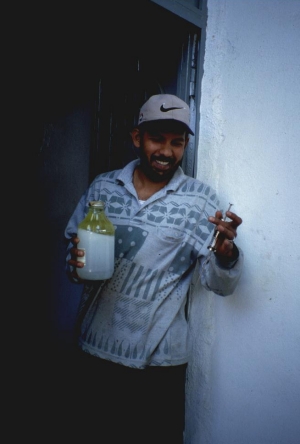

At this point the droplets of attar are still dispersed

in the rose water, so a second distillation takes place, in which the

globules of attar rise to the surface as the liquid cools down,

facilitating their collection with a device similar to a syringe. The

attar collected in just one of these containers produces one single

tolah (about 11.7 ounces) which, understandably, sells for between 2000

and 3000 Saudi riyals.

At first, the main purpose for distilling these delicate roses was to

produce rose water which is used at different festivities and

celebrations, like the two "Eid" or at weddings, for example. It's also

used as an ingredient in the kitchen for some dishes and, especially,

for desserts, sweets and some drinks. It is said that it is used as

well to perfume the Yemeni Corner of the holy Ka'bah.

At first, the main purpose for distilling these delicate roses was to

produce rose water which is used at different festivities and

celebrations, like the two "Eid" or at weddings, for example. It's also

used as an ingredient in the kitchen for some dishes and, especially,

for desserts, sweets and some drinks. It is said that it is used as

well to perfume the Yemeni Corner of the holy Ka'bah.

According to a

story, attar was discovered in the 17th century when a woman noticed a

sort of a scum formed on the dishes where hot rose water had been

poured. She collected it little by little, and was amazed as she

realized that that scum had an extremely rich rose perfume. Experts

claim that this scent is so penetrating that it stays in the clothing

where it was applied even after the fabric has been washed for several

times.

I too can vouch for that.

After coming back from our trip to the rose farm, I chose the best

among the roses which Ali had kindly given us. I put these in a wicker

basket but I couldn't bring myself to throw away the ones which, sad to

say, now looked crumpled, brown and withered, so I tossed them into a

clay bowl. Some days later I happened to need that same bowl, so I put

those dismal-looking remains into another container and I washed the

bowl. Days later, that humble clay pot still retained the

unmistakeable, unforgettable scent of the lovely roses of Taif.

I too can vouch for that.

After coming back from our trip to the rose farm, I chose the best

among the roses which Ali had kindly given us. I put these in a wicker

basket but I couldn't bring myself to throw away the ones which, sad to

say, now looked crumpled, brown and withered, so I tossed them into a

clay bowl. Some days later I happened to need that same bowl, so I put

those dismal-looking remains into another container and I washed the

bowl. Days later, that humble clay pot still retained the

unmistakeable, unforgettable scent of the lovely roses of Taif.

-Susana Pint

|