|

One of the attractions of the new

geopark will be The Giant Pumice Horizon, easily viewed inside

Jalisco's Primavera Forest. Within the Horizon you can see blocks of

pumice up to eight meters in diameter. One of the attractions of the new

geopark will be The Giant Pumice Horizon, easily viewed inside

Jalisco's Primavera Forest. Within the Horizon you can see blocks of

pumice up to eight meters in diameter.

By John Pint

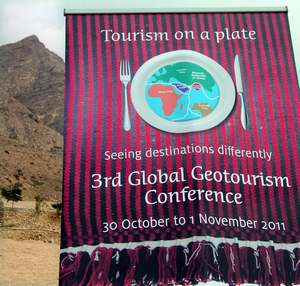

It all began in the Sultanate of Oman

where—thanks to a strange concatenation of events—I found myself

attending the Third

Global Geotourism Conference in the fall of 2011. While

preparing for this event, I discovered the existence of the Global

Geoparks Network, UNESCO’s organization of 90 geoparks in 27 countries

of the world, where tourists can see and, better yet, understand the

world’s most outstanding geological phenomena. It all began in the Sultanate of Oman

where—thanks to a strange concatenation of events—I found myself

attending the Third

Global Geotourism Conference in the fall of 2011. While

preparing for this event, I discovered the existence of the Global

Geoparks Network, UNESCO’s organization of 90 geoparks in 27 countries

of the world, where tourists can see and, better yet, understand the

world’s most outstanding geological phenomena.

I had planned to give a presentation at the conference on the

extraordinary biodiversity and geodiversity all around the city of

Guadalajara, an area I began calling “The

Magic Circle” in 2010 after discovering that all five of

Mexico’s eco-systems converge in close proximity to this city, the

second-biggest metropolis in the county.

Naturally, I asked myself whether any of the geological features near

Guadalajara might qualify for inclusion in a UNESCO Geopark. I decided

to pose the question to a friend and neighbor, Canadian geologist Chris

Lloyd.

“Can you think of any place in western Mexico,” I asked him, “that is

geologically rare and at the same time suitable for demonstrating

geological processes to the Man on the street?”

Chris looked at me and said, “John, you don’t have to go anywhere to

find a site like that. All you have to do is step out your door and

walk down the hill.”

Thus, did I

discover that I live right on the edge of what geologists call The

Comenditic Dome and Ash Flow Complex of Sierra La Primavera.

“Geologists come here from all over the world to see the Primavera

Caldera,” said Lloyd, “but they usually study it from the western

extension of Mariano Otero Street. Actually, the arroyo right here at

the edge of Pinar de la Venta is much better for understanding the

creation of the Giant Pumice Blocks, which, of course, only occur in a

few places in the whole world.”

Giant Pumice Blocks? A potential geopark in my

own backyard? “It could only happen in Mexico,” I said to myself as I

walked with Chris down to the Río Seco, a deep arroyo which separates

my community from the Primavera Forest. Soon we stood at the base of a

vertical canyon wall about 50 meters tall. “Welcome to the Primavera

Caldera,” intoned the geologist with a big smile. Giant Pumice Blocks? A potential geopark in my

own backyard? “It could only happen in Mexico,” I said to myself as I

walked with Chris down to the Río Seco, a deep arroyo which separates

my community from the Primavera Forest. Soon we stood at the base of a

vertical canyon wall about 50 meters tall. “Welcome to the Primavera

Caldera,” intoned the geologist with a big smile.

Now a caldera is a most interesting phenomenon. It’s a big hole which

is left after a huge volcanic explosion. The whole process happens so

suddenly that there is no time for a volcano to form. This particular

explosion, I learned, took place 95,000 years ago and it was no small

thing. Twenty-four cubic kilometers of rock and dust were thrown up

into the air, putting the Primavera Caldera solidly on the list

(although not at the top) of the World’s Greatest Explosions.

Eventually, the 11-kilometer-long crater filled with water and became a

lake for at least 10,000 years. “See the horizontal lines on the canyon

wall?” said Chris, “Each is a layer of sediment formed at the bottom of

that lake.”

Right on top of all those strata of sediment, I could see a thick band

of something completely different: a layer composed of ash and enormous

chunks of pumice typically from four to six meters in diameter. It

seems some 25-30,000 years ago, there was a Mt-St-Helen’s type eruption

from a volcano at the southeast end of the lake, near the modern-day

subdivision of Bugambilias. Giant blocks of pumice enclosed in a

pyroclastic cloud were shot into the air and landed in the lake where

they floated for a while until sinking to the bottom, forming a thick

layer which geologists now call the Giant Pumice Horizon.

Hot River and

Hissing Fumaroles

Apart from canyon walls

that show us the history of the caldera, the present-day Primavera

Forest has other outstanding geological features, such as Río Caliente,

a hot river which starts out with temperatures as high as 70° C (158°

F) but is quickly joined by numerous hot and cold springs, providing a

delightful, hot, bubbly, “natural Jacuzzi” experience to countless

thousands of bathers yearly. In addition to hot rivers, the Primavera

Caldera also has dramatically hissing, sputtering fumaroles. Some of

these have produced miniature forests of delicate, featherlike sulfur

crystals, a veritable Little Yellowstone that few visitors to the

Primavera have ever seen. Apart from canyon walls

that show us the history of the caldera, the present-day Primavera

Forest has other outstanding geological features, such as Río Caliente,

a hot river which starts out with temperatures as high as 70° C (158°

F) but is quickly joined by numerous hot and cold springs, providing a

delightful, hot, bubbly, “natural Jacuzzi” experience to countless

thousands of bathers yearly. In addition to hot rivers, the Primavera

Caldera also has dramatically hissing, sputtering fumaroles. Some of

these have produced miniature forests of delicate, featherlike sulfur

crystals, a veritable Little Yellowstone that few visitors to the

Primavera have ever seen.

Fairy

Footstools and Magic Rocks

In the western half of the Primavera Forest lie

hundreds of bizarrely shaped rocks. Some of them look like giant

bathtubs, sofas and armchairs, others resemble long, smooth, curving

fences or walls. Most curious of all are the “Fairy

Footstools” which, from a distance, look just like tree

stumps but are, in fact, made of rhyolite rock. Dig a hole next to what

looks like a stump and you’ll discover that they are just the tips of

very long, smooth lithic cylinders. Geologists refer to them as “Fossil

Fumaroles." In the western half of the Primavera Forest lie

hundreds of bizarrely shaped rocks. Some of them look like giant

bathtubs, sofas and armchairs, others resemble long, smooth, curving

fences or walls. Most curious of all are the “Fairy

Footstools” which, from a distance, look just like tree

stumps but are, in fact, made of rhyolite rock. Dig a hole next to what

looks like a stump and you’ll discover that they are just the tips of

very long, smooth lithic cylinders. Geologists refer to them as “Fossil

Fumaroles." A

very fine book on the geology of the Primavera Forest was published in

March, 2013. "La Apasionante Geología del Area de Protección de Flora y

Fauna La Primavera" by Barbara Dye has 72 full-color pages of photos,

drawings and sketches and easy-to-follow descriptions of the exciting

geology of this unusual caldera (Book Review). Outside

the confines of the proposed Geopark, lie a great many fascinating

geosites many of which could become "partners" with the Park at some

point. Below follows a list of some of these places.

El Diente Monoliths

A ten-minute ride north

of Guadalajara brings visitors into a forest of giant monoliths,

popularly known as El

Diente. These huge rocks are composed of a rather pure

feldspar porphyry which formed deep under the earth perhaps up to 30

million years ago. That’s how long it’s taken the surrounding rock to

erode away, leaving these extremely old monoliths standing tall. El

Diente is a Protected Area and a favorite site for rock climbers as

well as for families looking for a place to take a walk and have a

picnic. For geologists, however, El Diente is a very special place

indeed. A ten-minute ride north

of Guadalajara brings visitors into a forest of giant monoliths,

popularly known as El

Diente. These huge rocks are composed of a rather pure

feldspar porphyry which formed deep under the earth perhaps up to 30

million years ago. That’s how long it’s taken the surrounding rock to

erode away, leaving these extremely old monoliths standing tall. El

Diente is a Protected Area and a favorite site for rock climbers as

well as for families looking for a place to take a walk and have a

picnic. For geologists, however, El Diente is a very special place

indeed.

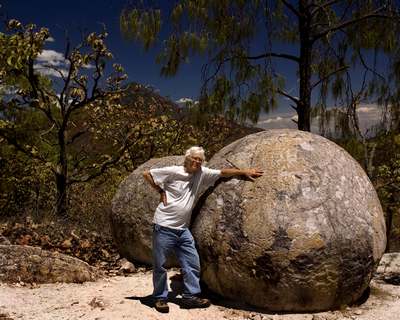

Giant Stone Balls

Within a short distance of

the Primavera Forest-Caldera, lie several other extraordinary

geological sites which could become partners with the new Geopark. Forty

kilometers to the west there is a hilltop covered with almost perfectly

round stone balls up to three meters in diameter. The

Piedras Bola, as they are called, so intrigued geologists

that National Geographic sent a team to Jalisco to unravel the mystery

of these megaspherulites’ origins and to publish the results (See their

August, 1958 issue). More than 70 of these round rocks have been

catalogued by a team from the University of Guadalajara (UDG) and it is

thought that hundreds more lie beneath the surface Within a short distance of

the Primavera Forest-Caldera, lie several other extraordinary

geological sites which could become partners with the new Geopark. Forty

kilometers to the west there is a hilltop covered with almost perfectly

round stone balls up to three meters in diameter. The

Piedras Bola, as they are called, so intrigued geologists

that National Geographic sent a team to Jalisco to unravel the mystery

of these megaspherulites’ origins and to publish the results (See their

August, 1958 issue). More than 70 of these round rocks have been

catalogued by a team from the University of Guadalajara (UDG) and it is

thought that hundreds more lie beneath the surface

Obsidian

Field and Workshops

Jalisco has the third

largest obsidian fields in the world. One of the most important of

these is El Pedernal, which is found 25 kilometers west of the

Primavera Forest, near Teuchitlán. Its obsidian is of a very high

quality and comes in many other colors beside black. Jalisco has the third

largest obsidian fields in the world. One of the most important of

these is El Pedernal, which is found 25 kilometers west of the

Primavera Forest, near Teuchitlán. Its obsidian is of a very high

quality and comes in many other colors beside black.

What is thought to be the world’s

largest and oldest obsidian workshop, Itztlitlan, is today

known as the former island of Las Cuevas, located 13 kilometers south

of Magdalena. Archaeologists have proven that high quality obsidian was

worked here continuously for 2000 years and tools from here made their

way as far north as what is today the US state of Arizona.

The Three

Major Types of Volcanoes

The Primavera is an outstanding example of a Caldera Volcano. Only 30

kilometers away, visitors can walk through the picturesque

crater of Tequila Volcano, a stratovolcano featuring one of the world’s

best examples of an uplifted volcanic plug. A safe, yet exciting via

ferrata can be constructed up to the very top. Good examples of the

third type of volcanoes, scoria cones, are found just east of

Guadalajara. This means that all three of the major types of volcanoes

can easily be visited in one day.

Tequila Volcano

The Opal Mines of Magdalena

Hundreds of opal mines lie 50 kilometers

northwest of the Primavera Caldera, near Magdalena. Wielding a miner’s

pick, visitors can find their own opals or purchase finely crafted opal

jewelry in Magdalena. Hundreds of opal mines lie 50 kilometers

northwest of the Primavera Caldera, near Magdalena. Wielding a miner’s

pick, visitors can find their own opals or purchase finely crafted opal

jewelry in Magdalena.

Guadalajara, it seems, has an abundance of outstanding geological

phenomena which fit the requirements for a UNESCO Geopark. Will it

happen? An ad-hoc committee has been talking about just this subject

for months, discussing the possibilities of creating a Geopark in

Jalisco with the help of Geopark experts living as far away as Iran and

China and with the local support of Bosque La Primavera. Here's hoping

that Jalisco authorities will be just as enthusiastic!

It

is proposed that the Bosque La Primavera Protected Area be declared a

Geopark.

The red elipse encloses other remarkable geosites, indicated by

green triangles, which could become "partners" with the new Geopark.

|